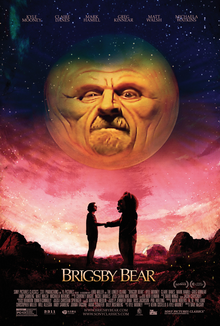

Lukewarm Takes # 19 Brigsby Bear

I had an ex-girlfriend whose favorite for movies was “nice.” When she would describe something as nice, I knew exactly what she meant, and in my mind at least, it always felt a little like a backhanded compliment. Love, Actually is nice. Citizen Kane is not. Great art seldom qualifies as “nice” and nice seldom makes for great art.

The older I get, the less inclined I am to judge “nice” and the more inclined I am to appreciate it, in entertainment as well as in life. Maybe it’s just the guy in the White House, but the world sure seems like it could use a whole more nice and a whole lot less angry and overflowing with rage, and I say that as someone who strives to be nice but sometimes finds himself overflowing with rage.

2017’s Brigsby Bear is a great film but it’s also a very nice film. That niceness has layers. It begins with the title character, a talking, anthropomorphic bear who isn’t just emotionally stunted man-child James Pope’s (Kyle Mooney) favorite television character but something close to a religion, a kindly, moral universe onto himself.

Like a more breakable Kimmy Schmidt, James has been kept from society by brilliant but mad toy designer Ted Mitchum (Mark Hamill) and his wife April for reasons that are never fully explained. Then one day the fragile unreality of his life is broken and James discovers that the people he thinks are his mother and father actually abducted him decades earlier and that Brigsby Bear is not a television character at all but rather his father’s creation.

What James thought was the widely loved adventures of TV hero Brigsby Bear was actually the work of his father, who is as inexplicably prolific as he is of questionable sanity. Brigsby Bear is a curious, amateurish creation designed to teach questionable and clumsy lessons, moral, educational and otherwise, but the filmmakers and the film treat him with an unlikely sensitivity and even reverence.

The movie honors the central role Brigsby plays in James’ obsessive imagination, even if he’s ultimately the creation of an enigmatic madmen. There’s a moment before James’ fragile world is torn asunder when James is signing off to what he imagines are his fellow Brigsby Bear die-hards (who, of course, are actually Ted and April) that’s startling and bracing for its complete lack of cynicism.

Seemingly any other movie would look down upon, and mock James’ obsession with a children’s stilted fantasy program but Brigsby Bear sees the positive in everything, not just kitschy fandom. It sees in James’ love of Brigsby and his desire to share that affection with what turn out to be fictional online friends a poignant attempt at connection and community and solidarity, like joining a cult or becoming a Juggalo.

That niceness and unexpected sensitivity extends to the film’s treatment of James after he leaves the curious yet oddly warm and satisfying cocoon of his old life as a treasured pet in a very large cage for an uncertain new world as the very confused son of Greg and Louise Pope (Matt Walsh and Michaela Watkins, cast very effectively against type as paragons of kindness and human decency) and brother of Aubrey (Ryan Simpkins), a surly teenager understandably irritated at having to now share a house and a life with a weird adult man with the maturity and life experiences of a child.

Brigsby Bear favorably reminded me of the holy trinity of Charlie Kaufman, Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry tonally but also in the way that it tells a very human, emotional story in a way that continually skirts fantasy and science fiction. There are some powerful fantasy elements to Brigsby Bear, like the idea that one obsessed patriarch could fund and create and direct and more or less make an entire low-budget television show by himself without anyone other than his wife and hostage knowing.

That requires some suspension of disbelief but not as much as the film’s depiction of Aubrey’s friends as a bunch of super-attractive teenagers on cool drugs who are overwhelmingly nice and empathetic and understanding about the weird outsider in their midst.

Brigsby Bear doesn’t even judge the aforementioned sexy, drug-doing teenagers for doing drugs alongside and with, what is essentially a very sweet but very myopic ten year old in a middle-aged man’s body. That, friends, is some radical acceptance.

The attractive young people in his sister’s circle don’t just refrain from making fun of James: they’re actually sucked into his fantasy world and his crazy dream of taking ownership of Brigsby and his world. Brigsby Bear is one of the more original movies I’ve seen in the past decade but it positively recalls Be Kind Rewind and The Disaster Artist in its loving, underlyingly tender portrayal of how we tell and re-tell stories as a way of trying to understand a confusing and complicated world and be understood.

With the help of his enthusiastic new friends, our protagonist sets out to make a movie about Brigsby Bear, a sort of epic work of fan fiction for a character that previously existed only as one very unusual boy’s epic, ongoing bedtime story. James tries to make Brigsby Bear a reality but his Brigsby-centered fantasy world has a way of brushing up hard against the painful realities of his life as a deeply damaged survivor of a very strange and singular form of trauma James didn’t see as traumatic at the time, and still sees in a fairly positive life even after everything comes out.

Brigsby Bear is a masterpiece of mood and tone. The filmmakers, and particularly Mooney, who is so good and so distinctive that it is impossible to think of anyone else in the role, walk a tonal high wire act throughout. If things get too wacky or broad for even a moment, then the movie’s fragile spell risks collapsing. But Brigsby Bear manages to maintain a tricky, fragile tone throughout, a sort of waking dream of pop culture kitsch reimagined as a crude but powerful sort of religion a zealot is reluctant to let go of even when the entire foundation it is built upon shattered.

Then again, as an adult who is pathologically obsessed with the long-running children’s program Sesame Street and who was raised, if not in captivity, then at least a group home for emotionally disturbed adolescents, where my only, constant escape was through pop culture, Brigsby Bear speaks very directly to my interests as a pop-culture writer, sure, but also to some of my fundamental psychological damage.

Because while I can mount an intellectual argument for Sesame Street as one of the all-time great shows, and one with a lot to offer adults as well as small children, and that would be true the fact of the matter is that there’s something about the show’s nice, endlessly accommodating and positive world that appeals to my frazzled, depression-addled brain.

I’m not as severe a case as the film’s protagonist. For me, it only feels like I was raised in captivity and socialized, or rather not socialized, different than every other human being in existence. That’s James reality, such as it is. But metaphorically and not even that metaphorically, I sure could relate to Brigsby Bear in a way I imagine people with more conventional childhoods did not.

I try my damnedest to be at least mostly a responsible grown-up. I feel like I owe that to my wife and three year old son. But, to be honest, I would probably list Cookie Monster high among my favorite performers. Oh sure, you could argue, and it certainly has been argued, that Cookie Monster is nothing more than a puppet formerly voiced and operated by Frank Oz.

Good dude. Enjoys cookies.

On some level, that might be true but consider this: I interviewed Frank Oz around the time Death at a Funeral came out. He was a real asshole. Very, very unpleasant. Absolutely tore me a new asshole for improperly phrasing a question. Granted, as something of a bitter asshole myself, I would probably be at the very least annoyed by being asked a badly phrased question but it made a strong enough impression on me that I still think about it fairly often.

So you see, Frank Oz the puppeteer, is a bit of an asshole, but Cookie Monster, he’s a good dude. A genuinely nice chap. A little obsessed with cookies, to be honest, but not in a destructive way. Same thing with Elmo. Whatever problems Kevin Clash may have encountered, that Elmo is a delight.

Do I think of Elmo and Cookie Monster as real, and not fictional characters on a children’s program? Probably, and on that level, nothing that could ever happen offscreen could ever change my feelings about them.

Maybe I dug Brigsby Bear because I am envious that I am too self-conscious to publicly admit that I watch Sesame Street by myself, although I guess I just did, while the film’s protagonist lures many of his friends and family members into being an active part of his fantasy world.

I wish the world was as nice as it is in Brigsby Bear, but I appreciate that that for 97 minutes at least we can escape into a dream world that’s arguably excessively kind as opposed to excessively horrible, the way the real world sure seems to be these days.

Support Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place, man, and get instant access to patron-only articles at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace