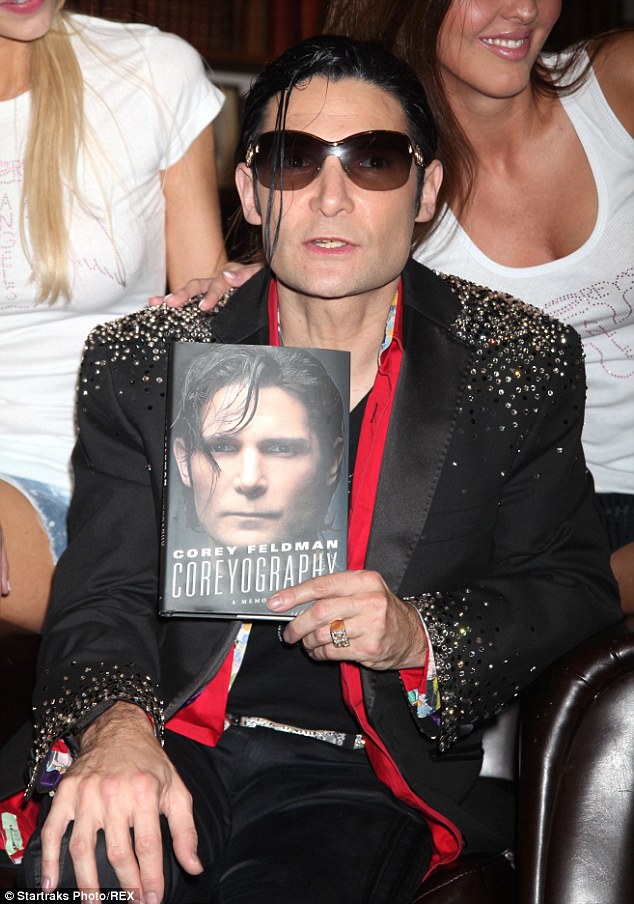

Exploiting our Archives: Literature Society: Corey Feldman's Coreyography

The 2013 tell-all memoir Coreyography, which chronicles the horrific sexual and physical abuse actor, musician, producer, dancer, icon, and one-man industry Corey Feldman endured during his simultaneously accomplished and almost inconceivably brutal and tragic teen year, benefits tremendously from the low expectations inevitably greeting both a literary work by Corey Feldman, as well as a book titled Coreyography. Feldman seems doomed to live the rest of his life as a walking punchline, a glib joke, a kitschy 1980s pop culture reference who also happens to be a human being with a soul.

Feldman’s memoir is his opportunity to share his truth, to bare his soul, to tell his story, to break free from the strictures of his sometimes cartoonish and mockable public persona and finally be real. On that level, the memoir is an unexpected revelation that’s just as riveting the second time around, if not more so, because now, when Feldman mentions National Lampoon’s Last Resort or Rock ’n’ Roll High School Forever in passing, I don’t have to just imagine what they’re like because I’ve seen them. Every last goddamn motherfucking ever-loving sucky minute of each of them, and several more exactly like them.

Having spent nearly a month inside Corey Feldman’s world, I got more out of his memoir than most but you do not have to be unhealthily obsessed with the minor former child star to find Coreyography riveting. It can be difficult to reconcile the Feldman of Coreography who looks back on his past with sadness, hurt, insight, pitch-black humor and bottomless compassion for the abused and lost child he used to be with the Feldman who habitually dresses like a combination of all of Johnny Depp’s worst characters post-Pirates of the Caribbean (which is to say pretty much all of them) and has staked his professional future on a lingerie-clad all-female backing band/weird-semi-cult composed of semi-runaways he calls Corey’s Angels.

Feldman never had a chance. In the poignant early chapters of Coreyography, Feldman paints a heartbreakingly vivid portrayal of an irrevocably broken, sad family that neglected the emotional needs of its children but was always ferociously present when a paycheck was being dispensed.

Feldman’s dad is a perpetually stoned, physically abusive small-time musician whose career peaked when he played in a lesser, latter-day incarnation of Strawberry Alarm Clock who reeked of marijuana at all times and who only became interested in his son when being the man in his life became an unexpectedly lucrative position. Feldman’s mother is even less functional. She’s a disconcertingly sexy former waitress ata Playboy Club who somehow managed to be completely emotionally absent from her son’s life while remaining a terrifying and abusive stage mother.

The author conjures up a lost late 1970s and early 1980s world of wood paneling and Star Wars action figures being played with by lonely children forced to grow up too fast while their parents remain children, getting high and screwing in the backseat of cars and trying to realize their show-business dreams through their children because they never came close to making it, and will never forgive themselves or their successfully miserable child for succeeding where they failed.

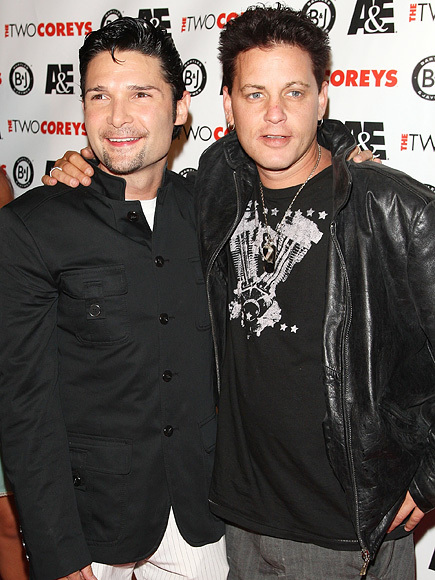

I think the book resonated with me on an additional level because it felt like Feldman was growing up in the suburbia of Steven Spielberg and Joe Dante of the 1980s, with all of its loneliness, and sadness, and wonder and horror. Of course, in a very real way, Feldman was living in that world in the sense that he actually acted in beloved Dante/Spielberg movies from the era like Gremlins, The Goonies and The Burbs as well as Stand By Me. Feldman was acting out the biggest fantasies of kids like me on movie screens and in fan magazines but behind closed doors Corey Haim and Corey Feldman led lives of decadent torment. They lived out our dreams in public but their lives were waking nightmares in private.

Feldman’s older sister was a child star of some renown, popping up in the cast of a 1970s incarnation of The Mickey Mouse Club. But as Feldman notes with world-weariness here, once it became apparent the cute little boy with the chubby cheeks and the off-key warble was the family’s financial future, his parents increasingly lost interest in his sister’s career. By the age of 10, her career was irrevocably in the decline.

Such is the nature of child stardom.

There’s a sense throughout Coreyography that Feldman is mourning his childhood. He’s mourning his abandonment, his high-profile isolation, his inability to trust the world or the adults who were supposed to protect him but almost invariably betrayed him. He can be melodramatic in recounting the failings of the people around him, and his own resilience, but it’s hard not to feel for the sad little boy, the latchkey kid and unhappy bread-winner wondering if his perpetually erratic mother would be up before noon to feed him, or up before noon at all.

Feldman writes lovingly and compellingly of father figures like Steven Spielberg, Richard Donner and Michael Jackson who ranked among the most powerful men in all of entertainment yet were unable to protect him from the kind of horrific childhood sexual abuse Feldman convincingly depicts as epidemic in show-business.

Child stars are richly validated and rewarded for doing what adults tell them to do on television and film sets. Feldman convincingly depicts the world of children’s casting and children’s entertainment as being full of pedophiles taking awful, unforgivable advantage that when child stars leave the set that powerful conditioning to conform to the demands of adults in position of power does not end.

For Feldman, the 1980s were the apex and the nadir, and it almost all happened before he left his teens. Feldman had no real friends, except for people like Steven Spielberg, The Goonies director and The Lost Boys Executive Producer Richard Donner and Michael Jackson, except in the case of Jackson the relationship was more of a same-age brother type deal. That had to be a little strange: you can’t impress the goths or the stoners at the prep school where you briefly matriculate but you can take some comfort in your friendship with, literally, in Spielberg and Jackson, the two most powerful and beloved figures in all of entertainment at the time.

Feldman and Haim!

Feldman had friends in high places and an impressive run of successful and/or iconic movies that includes Gremlins, The Goonies, Stand By Me, License To Drive, The Lost Boys and the original live-action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. He had what every star-struck kid hungers for but not what he needed most as a suicidally depressed, abused and drug-addicted teenager: security, stability and parents who can be trusted and relied upon.

There is innocence in Feldman’s story. His account of filming The Goonies and Gremlins is filled with genuine, child-like awe for the magic of filmmaking. He captures how exquisitely overwhelming it must have been to segue improbably but inevitably from being a chubby-cheeked Michael Jackson super-fan who watched his legendary performance on Motown 25 so that he could dance exactly like his idol, to having Jackson call him up at the height of his surreal super-fame, so that this strange adult and this sad, motherless and fatherless child could talk for two and a half hours about everything and nothing.

Despite Feldman’s teen idol status, powerful connections and string of box-office hits, he was, in many ways, powerless in a way only a child with too much money and too much fame and no self-control or responsibility can be. Coreyography is a book that could only have been written with the kind of perspective that can only come with time and age.

Feldman is excruciatingly honest discussing how his actions at a young age may have played a crucial role in his License to Drive co-star and instant best friend Corey Haim getting molested by the many predators and child molester in their social circle, and how Feldman similarly may have gotten Haim hooked on coke by doing blow with him while he was still a neophyte in the ways of hard drugs.

Not a good look

These were the 1980s, and cocaine was everywhere. Feldman was fifteen years old and part of Sam Kinison’s notorious wild-man circle, engaged in cocaine consumption contents with the bad boy comedian and getting blow jobs from porn stars in parking lots. Then it was on to heroin and crack and until he just kept getting arrested for heroin possession so often that he finally got the hint and managed to kick, albeit without the occasional awful relapse. Feldman writes of the horrors of drug addiction and abuse but also of its pleasures, how seductive it can be to a confused kid convinced, with reason, that he’ll never be able to live a normal life, that by twenty he’d fucked up his brain and his life and his career too badly to ever really recover.

This achingly honest memoir is particularly adept at chronicling the tragic, contradictory and toxic psychology of molestation and drug addiction. Feldman and Haim would seek out sketchy adults, or sketchy adults would seek them out with gifts of cocaine and heroin and Ludes and everything else growing boys should avoid, and then molest Feldman and Haim while they were incapacitated or take advantage of their desperate need for validation and human connection.

These adult predators kept Feldman locked in a vicious cycle of abuse and shame: they’d feed Feldman’s voracious drug habit, then sexually assault him when he was at his most vulnerable. But rather than kick them out or report these child molesters to the police, they kept them in their inner circle, lived together and even gave them jobs. At one point one of Feldman’s molesters worked as his personal assistant.

Ain't I a stinker?

That might seem insane but the actor/musician was filled with shame over both his voracious abuse of hard drugs and being molested and terrified of being alone, so at his weakest, he would rather live with a man who fed him hard drugs and assaulted him than live by himself. In one of the most heartbreaking moments in a memoir filled with them, Feldman reflects that he kept child molesters and sexual predators in his circle for years during and after the abuse, but he never slept alone. He and Haim were willing to endure just about anything to not feel lonely and Hollywood was full of people overjoyed to take advantage of that insatiably need for validation, company and attention. And of course hard drugs.

So, so many terrible, terrible hats.

Haim emerges as a beautifully realized, almost Shakespearean figure despite only being a supporting player in this story. The Corey referred to in the title is most assuredly Corey Feldman, but it’s Haim who is the most unforgettable character. He’s a real sweetheart who, in Feldman’s account at least, was destroyed psychologically by getting raped as a boy by what Feldman describes as a super-powerful major Hollywood player (Look at the cast of Lucas and you can probably figure out the (allegedly) guilty party) and became a hyper-sexualized, motormouthed whirlwind of self-destruction as a teenager and an adult, a kid who was continually looking for trouble and generally finding it.

Unlike Feldman, Haim never got his shit together. And it took Feldman a long time to pull out of a very huge hole created by drug addiction and bad behavior. Every time he gets busted with balloons of heroin it’s back to the clink, or back to rehab, until the next time. Yet Feldman managed to kick drugs and get his life back on track in time to appear in a slew of forgettable direct-to-video sex comedies and gimmicky reality shows.

More than anything, Feldman is a goddamned survivor. I respect the hell out of that. The glory of Feldman’s story is not that he was once so successful and today keeps hope alive but rather that he’s survived things that would have killed most people. Coreyography is consequently haunted with ghosts, of friends and mentors that are no longer here, of bad scenes and regrettable characters and Feldman’s lost innocence.

This picture of Nick Offerman and Corey Feldman on the set of The View makes me happy.

It helps Feldman’s case that Corey’s Angels, his weird new project, is mentioned only in passing, as one of a number of projects he’s excited to be working on as a businessman and performer and not some weird T&A rock and roll cult. The memoir was published in 2013, however, so it wasn’t as big, and as troubling, a part of Feldman’s life and career and mythos as it is now. The Feldman of Coreyography has been through hell and emerged with a sense of perspective and even hard-won wisdom. I don’t know what the hell is going on with the Corey Feldman who made headlines again when his performance on The Today Show was met with near-universal mockery and accusations that Feldman was a creepy weirdo who makes terrible music.

Despite the enormous sympathy I have for Feldman as a human being, activist and abuse survivor, people who have ridiculed Feldman as a creepy weirdo who makes terrible music aren’t exactly off-base. Hell, I love Feldman, and am unhealthily obsessed with him, and I will be the first to concede, in all fairness, that Feldman is a creepy weirdo who makes terrible music.

Feldman may be a walking punchline, but Coreography is a gripping and important book of unusual candor and bravery. It deserves to be read, particularly by potential stage parents and/or the parents of child actors.

Yet it’s impossible to forget that Feldman is still the kind of unabashed cornball who concludes his book with Troy McClure-level sentiments like “Despite the highs and lows, the ups and downs, the peaks and valleys, I’ve never lost sight of my spirituality; I owe so much to God and continue to put my faith in Him. I’ve never taken for granted the love and support of my fans; they drive me to keep creating. I’ve never stopped trying to be a positive voice, raising awareness for the causes that are near and dear to my heart. And I’ve never stopped trying to make the world a better place for our children. I’ve never really taken a break—and I have no intention of taking one now.”

Feldman closes by saying “Really, I’m just getting started” which is a lovely, optimistic sentiment, one worthy of a positive person who has never taken the love and support of his fans for granted, nor lost sight of their spirituality, but if I may be brutally honest, it’s probably not true. Judging by Coreography, Feldman has squeezed several lifetimes worth of drama and trauma and triumph and sadness into 46 years, so I wish for him a lifetime with less drama and a whole lot more peace.

Support Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place, Feld-Month and more months like Feld-Month over at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace