I Wrote About the 1976 Field-Goal-Kicking Mule Movie Gus Because This Is My Website and There's Nothing in the Rulebook That Says I Can't

Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place has been a goddamn blessing. It’s easily one of the best things that’s ever happened to me, personally or professionally. Having to create such an enormous amount of content every day has challenged me in the best possible way. I feel like I’m realizing one hundred percent of my potential writing the site. That is a wonderful feeling.

It’s also a wonderful feeling to wake up every weekday and feel like you have something special to share with the world, but more specifically your readers, not just random web surfers looking for snarky news posts.

It feels wonderful to wake up every morning excited to communicate with commenters here, to have something that, in this embryonic state, at least, is pure, that reflects my sensibility in its truest and most personal form.

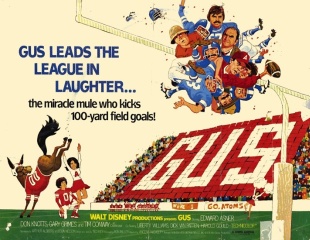

Yes, Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place and the support of readers and patrons like y’all has changed my life for the better. If not a life-saver, this has certainly proven to be a career-saver. But the best part about having my own website, beyond the freedom, autonomy, independence, support and community, is that if I decide to watch Gus, the 1976 Disney movie about a Yugoslavian field-goal-kicking mule, and then write a 2000 word article about it, no one can stop me.

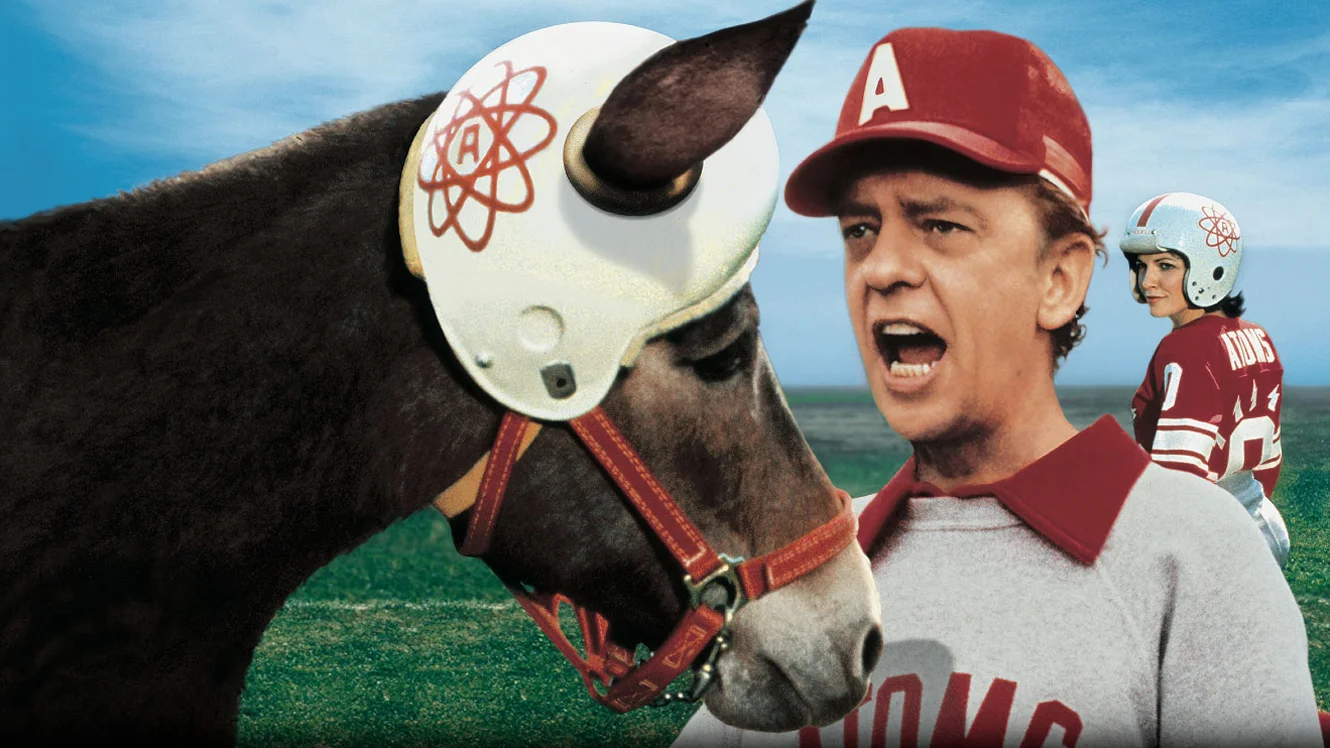

I've got Gus-level swag these days, if that's okay with you

I don’t even have to create some bogus column idea as a pretext for writing about Gus, although my brain operating the way that it does, I did so anyway in the form of “Shaggy Sports”, a new column chronicling the wild and wooly world of sports involving sports-playing animals and werewolves.

Will Shaggy Sports take off the way My World of Flops or Control Nathan Rabin has? No, it will not. Will it be regularly updated? Probably not, although I have kind of been looking for an excuse to write about the Teen Wolf Blu-Rays Scream Factory just put out. Honestly, folks, I just want to live in a world where a man like me can do things like write about Gus and be able to support myself and my family with my labor.

But I’m also writing about Gus because there’s absolutely noting in the rulebook that says that I can’t.

And having finally satiated 41 years of curiosity about the movie with the Yugoslavian mule that kicks hundred yard field goals (Yes, I was curious about Gus before I was able to talk), I'm pleased to report that the reality of Gus is even more impossibly beautiful and perfect and pure than I could have dreamed of. You’d think a premise like a field-goal kicking mule would be impossible to live up to, but it's not.

I could explain this still but I'd rather just respect the mystery

The magic begins in Yugoslavia with some of the most exquisitely fake rear projection I’ve ever seen. The rear projection is so hilariously unconvincing that whenever it’s employed to give the illusion of depth and massive crowds, it just looks like the stars are standing in front of a giant, extremely blurry, dirty television screen displaying a large, out-of-focus mass of impossibly fuzzy human beings.

We’re introduced to Andy Petrovic (Gary Grimes, in the role that launched him to anonymity), an inept Eastern European farm boy blessed but mostly cursed to live forever in the shadow of his brother, one of the best soccer players in Yugoslavia. How do we know? Well, early in the film Andy’s dad tells Andy, “Watch your brother, the second greatest soccer player in all of Yugoslavia!”

How can a man whose life seems to consist of falling down, falling down things (including a well) and being embarrassed by his father compare to the glory and heroism of his older brother, who rumor has it is nothing less than the second-best soccer player in Yugoslavia? Thankfully Andy has a mule named Gus capable of kicking a soccer ball one hundred yards.

That, in itself, is not impressive. What American gives a fuck about soccer? Thankfully, Gus has a more important talent as well: he can kick a football a hundred yards. This brings him to the attention of Hank Cooper (Edward Asner), the cranky owner of the California Atoms, a team that somehow manages to go entire seasons without scoring a point, let alone winning a game.

Gus becomes a human interest story in Yugoslavia that reaches Hank, who tells his plucky, mule-loving assistant (who will become Andy’s love interest) “Even if I was Yugoslavian, I’d have trouble laughing these days.” I am pleased to report that that is wonderfully representative dialogue in a role that plays more like an extended and successful assault on a proud man’s dignity.

Between Mary Tyler Moore, Lou Grant and his leftist political activism, Asner has developed a reputation as a fearless seeker of truth and justice, but to me the undisputed highlight of his life is the career-defining moment when his character here tells his confused coaches, with the same unearned swagger President Trump brings to everything that he says, “The mule stays in. AND he kicks.”

Why isn’t that moment number one on every list of sports movie highlights? Probably because it has to contend with the even more iconic moment here when play is laboriously interrupted after Cooper decides to bring in Gus to kick a field goal and the rule book is consulted before it is announced over the loudspeakers that the rules merely say that 11 players must be on the field, without specifying species or gender, so, astonishingly, there’s nothing in the rule book that says a mule can’t play football or kick field goals.

I try not to be a stickler for verisimilitude when it comes to movies about animals improbably gifted at athletics but I’ve got to admit this is where the movie lost me a little. I’d have no problem believing a mule could kick thirty or forty yard field goals with unnerving accuracy. It probably happens all the time. But one hundred yards? C’mon, that’s just not realistic. Sorry.

I'm pleased to report these fragile dishes make it to the end of the film unharmed and intact.

Bob Crane provides the only intentional laughs as Pepper, a motormouth announcer who never shuts up long enough for partner Johnny Unitas to say anything, a dynamic that at its best recalls a similar vibe between Fred Willard and his announcing partner in Best in Show. Unitas, one of a number of real-life football players in the cast, makes for a surprisingly able straight man to Crane, whose loving lampoon of a supreme narcissist of the airwaves marked a breezy return to his early days in show-business as a popular LA DJ whose machine-gun delivery and wholesome charm won the attention of the makers of POW camp-themed-and-set wacky sitcoms.

Gus constitutes Crane’s final and most unforgettable appearance, not counting his many appearances in early homemade pornography of his own devising.

Sports are exciting (theoretically, at least) because there are so many intriguing variables. Anything could happen so it’s exquisitely perverse for Gus to envision a sports world almost entirely devoid of the variables and the surprises that make sports sports.

Gus shows very little of the actual games Gus wins more or less by himself. I suspect that’s because, judging by the film, the filmmakers have only a passing familiarity with football, and its rules, but also because watching someone do the same thing over and over and over and over again is by definition boring, even if it’s something like an Eastern European mule kicking a hundred-yard field goal. Having Gus always kick hundred yard field goal to single-handedly win games is like expecting audiences to be emotionally invested in the outcome of baseball games always won by a robot that invariably hits home runs in the exact same way.

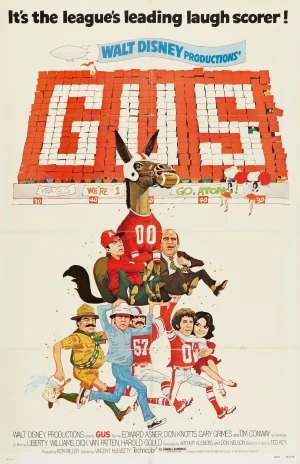

Gus never misses unless his oats have been laced with alcohol by low-level criminals played by Tom Bosley and Tim Conway, who lead a semi-star-studded cast that’s a veritable “who’s who” of people you would imagine would be in a 1976 Disney live-action comedy about a field-goal kicking mule, including, but not limited to, Dick Van Patten, Harold Gould, Bob Crane, Dick Butkis, Johnny Unitas and Richard Kiel.

Kiel plays a character identified only as “Tall Man” and I hear that during auditions he loomed head and shoulders above the competition. Ha! We have fun here. Actually there’s a scene where Kiel stands up through the sun roof of a Volkswagen Bug (an in-joke perhaps to the director’s work on the Love Bug series, particularly its later installments) that recalls a similar gag in The Simpsons involving a similarly comically large man in a comically small car.

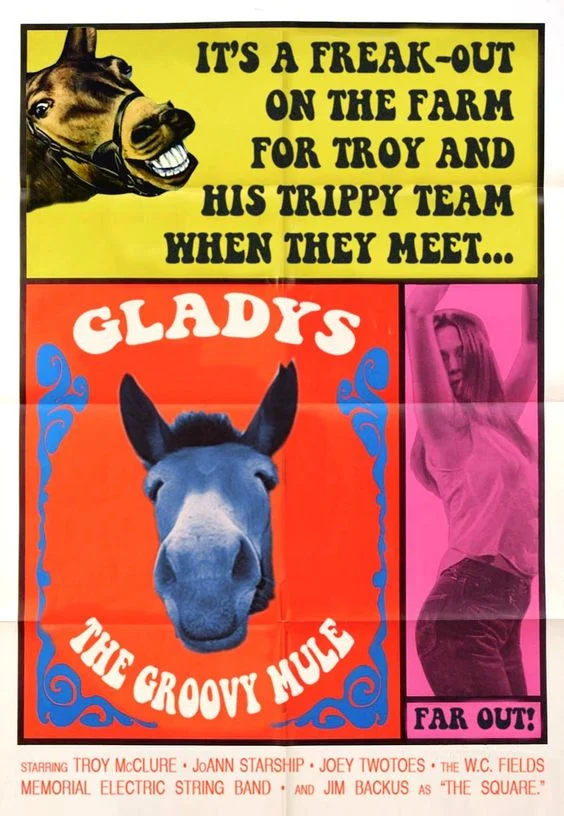

That’s not the only time I thought about The Simpsons while watching Gus. If Gus did not exist The Simpsons would have to create it, which they kind of did with Gladys, The Groovy Mule, whose name, animal and idiocy references both Gus and the Francis the Talking Mule series.

It goes beyond that. The name of the team takes from the gutter to the Super Bowl is named the California Atoms, not unlike the Springfield Atoms. Incidentally, if you were to find me a "California Atoms" jersey and send it to me. I will be your best friend forever. It’s easy to imagine actual dialogue from Gus like the following as spoof dialogue of a comically terrible kid’s movie in a golden-era episode of The Simpsons

* “No mule is going to outsmart us!”

* “That mule’s gone ape! What’s the matter with him?”

* “The mule knappers are on their way to the rock pile!”

* “Gus the Mule? I got that Yugoslav coming out of my ears!”

* "Never switch mules in the middle of a shave.”

Knotts and the mule who plays Gus apparently really hit it off when they took this picture together. You can tell. Their chemistry really comes through

Since there’s no suspense regarding games where Gus is working his magic, the filmmakers introduce the unlikely criminal duo of Tom Bosley and Tim Conway as a pair of recently released jail birds tasked with ensuring Gus doesn’t make it to his games through a series of low-level ruses, or that Andy doesn’t make it to the game, or, if Gus does indeed make it to a game, he’s too soused on booze to effectively kick a hundred yard field goal.

I am not too proud to concede that I laughed, and laughed loudly, when Gus drunkenly sat on a football instead of kicking it through the goalposts. Was I laughing with, or at, the movie? I’m pretty damn sure I was laughing at the movie, and the movie seems fine with that.

Gus is very comfortable with its own ridiculousness. It remains snugly in a pocket of oblivious self-parody throughout, right up until a climax that calls upon Gus to kick a hundred and ten yard field goal, and, when he stumbles, for Andy, who had never done more than hold the football and yell encouragement to his magical mule, to run one hundred yards to win the game and finally prove himself to his father, and to society, and to emerge from the shadows of both his brother and mule.

I don’t want to be “that guy”, but the scene where Andy goes from never having done anything but hold a football for a horse to kick to running for a hundred yard touchdown is one of several moments where the film strains credibility.

There. I said it.

I will close by saying that Gus is far more righteously, unabashedly stupid than I ever imagined even a movie about a field goal kicking mule could possibly be, and that might be the single highest praise I have ever given anything.

Support Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place, Shaggy Sportsman and the beautiful dream of a man being able to make a living writing about ridiculousness like Gus over at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace