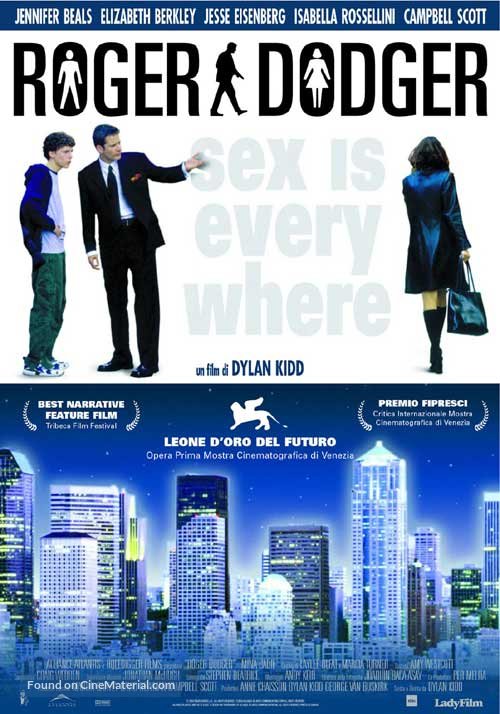

Control Nathan Rabin 4.0 #30 Roger Dodger (2002)

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the site and career-sustaining column that gives patrons an opportunity to select a movie that I must watch and write about in exchange for a one time, one hundred dollar pledge to our Patreon account.

I write about horrible movies for a living. So it’s not surprising that the movies I’ve covered for this feature have tilted heavily towards the unspeakably, surreally awful. Sometimes that awfulness becomes transcendent and fascinating, like previous entries Rad and Miami Connection. Sometimes y’all just want me to write about a Police Academy sequel or late-period Mel Brooks sub-mediocrity and I am totally cool with that. I am beyond cool with that. I’m alarmingly, distressingly appreciative that for the time being at least I’m able to make a living writing about my beloved garbage.

But sometimes readers want me to write about movies that are not fascinatingly, singularly terrible for this feature and I’m grateful for the change of pace. Despite vague memories of liking 2002’s Roger Dodger very much (if I recall correctly, it made my top ten list) I took my sweet time re-watching it.

I’m glad that I did because I ended up re-watching Roger Dodger not long after writing the liner notes for the Criterion Collection Blu-Ray of Mikey & Nicky and one of the many things I like about writer-producer-director Dylan Kidd’s acclaimed debut is how much it reminds me of Elaine May’s unflinching exploration of toxic masculinity.

Like Mikey & Nicky, Roger Dodger is a darkly funny comedy-drama about two men drinking and talking and bullshitting and chasing women and trying desperately to get laid, more to bolster their perpetually threatened sense of their masculinity and virility than out of any real desire for sexual gratification or release.

Elaine May was enormously prescient in her depiction of toxic masculinity but our understanding of misogyny, entitlement and male fragility have evolved tremendously since then. When I first saw Roger Dodger not long after the turn of the millennium in my capacity as a professional film critic for The A.V Club I saw Roger, the rage-choked copywriter Campbell Scott plays magnificently, as a deeply flawed anti-hero or a garden variety misogynist.

From the viewpoint of 2018, however, he cuts a decidedly darker, less sympathetic figure. For much of the movie Roger comes off as what are known as “pick up artists”, awful, awful men who see the entirety of male-female romantic relationships as a cynical, rigged game where the only goal is to have sex as often as possible with the most attractive partners.

Like Dennis in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Roger has a system rooted in what pick-up artists refer to as “negging”, or strategically insulting a woman you want to have sex with as a way of bruising their self-esteem and sense of attractiveness to the point where they’ll feel the need to have sex with the man verbally abusing them as a way of re-establishing their desirability.

Roger says horrible, horrible, unforgivably cruel things to the attractive strangers he wants to have sex with in Roger Dodger but his cynical belief in the power of “negging” extends to his understanding of his job as a hotshot, albeit soon to be unemployed copywriter. Roger sees his work, perhaps not inaccurately, as undermining the self-esteem of the American consumer so that they’ll feel worthless and inferior and doomed to die alone and unloved unless they purchase whatever consumer product is being advertised.

If someone approvingly quotes Campbell Scott from this film, get the hell away. They are a bad human being.

We’re introduced to Roger, a sort of sociopathic latter day would-be Don Draper, holding court at a bar with coworkers who include Joyce (Isabella Rossellini), his boss and lover. We catch him deep into a never-ending rant depicting women as a threat to the virility, usefulness and power of men on a biological and evolutionary as well as social level.

He’s talking for the pleasure of hearing himself talk. But he’s also talking because he sees everything as a game to be won or lost and he’s not about to let any of his professional peers win the meaningless game of dominating that night’s conversation.

Roger’s friends seem amused and annoyed by him in equal measure. He’s smart and, because he’s played by Campbell Scott, intimidatingly handsome in a cold, WASP manner but he’s nowhere near smart or attractive enough to get away with being such a raging, world-class, unrepentant asshole. Roger seems tragically unaware that opening his mouth and talking makes him infinitely less attractive to the women he’s trying to fuck.

Joyce treats Roger like a toy that once gave her tremendous pleasure but that has outlived its usefulness. So she breaks up with Roger even if it seems clear that in her mind at least, they were never anything more than fuck buddies. Getting dumped not just by a woman but by his substantially older boss wounds Roger deeply. In his desperation and hurt he lashes out by trying to hurt as many people as possible while also trying to have sex with them. To womanizers like Roger, there’s no contradiction between those two impulses. On the contrary, they’re complimentary impulses. Roger relentlessly pursues casual, meaningless, demeaning sex because that’s a way to hurt women the way he feels he’s been hurt by Joyce.

Roger’s downward spiral is interrupted by the unexpected appearance of Nick (Jesse Eisenberg, in his film debut and star-making performance), his 16-year old nephew. Nick is in town interviewing at Columbia and has the questionable judgment to seek out an uncle who is as bad at being a brother and son and uncle as he is in every other facet of his life.

When he discovers that the fawn-like progeny of his estranged sister is a virgin this horrible, toxic man’s awful night suddenly becomes infused with a sense of meaning and purpose. He now has a mission. Roger knows what he must do: he must get his nephew laid. It’s Roger’s chance to make it up to the great Gods of sex for the crime of getting dumped by his boss by ushering his nephew into the complicated, fraught, exciting and terrifying world of hook-ups and casual sex, closing time flings and disastrous one-night stands.

Stick with me, kid. You’ll be badly photoshopped like you can’t believe!

Roger functions as a douchebag Yoda to his inexperienced relation’s adorably neurotic Luke Skywalker. Alternately, he’s Phil Jackson dispensing life lessons as well as coaching advice as he tries to get his protege off the bench and on the board. For Roger, sex is about domination. It’s about winning. It’s about volume. It has nothing to do with love or emotional connection.

In his capacity as the world’s sleaziest life coach, Roger takes Nick to a bar where they strike up a flirtation with Andrea and Sophie, single women on the town played by legendary beauties Elizabeth Berkley and Jennifer Beals of Showgirls and Flashdance respectively.

Roger wants Nick to do anything in his power to get laid, particularly if it’s unethical and amoral, but when the women seem infinitely more interested in the teenager’s stumbling, fumbling innocence than his uncle’s curdled, verbose “worldliness” the older man becomes threatened and emasculated and lashes out at the women in a way that ensures that nobody will be getting laid that night, even after Nick enjoys a long, warm and tender kiss with Sophie that stands as the film’s only real moment of emotional connection.

Roger acts like what he wants is sex but what he really wants, what he needs, what he lusts for, and desperately lacks, is control. He lost what little control he had in his relationship with Joyce when she dumped him and when two women Roger wants very badly to sleep with lose interest in him quickly and deservedly, he ruins things for his erstwhile student in an angry, bitter, doomed attempt to regain control.

Roger is of the mindset that the quickest way to a woman’s heart is through her self-loathing and self-destructiveness. He tries to infect Nick with his ideas and his poisonous sexism but as the night grows darker and darker it becomes apparent just how little control and power Nick has in his life and particularly in his career.

After a disastrous visit to a work party where Roger tries to convince Nick to try to have sex with a professional colleague on the verge of passing out Roger decided to implement what he referred to earlier as the “Fail-safe:” getting Nick laid at an underground sex club where a nameless naked woman will have sex with him for one hundred dollars.

In the sex club sequence, Roger’s emptiness and loneliness are laid bare. For him, everything in life comes down to a sleazy, self-interested transaction. When clever conversation, good looks, provocative ideas, charm, confidence and good old fashioned insults and emotional abuse don’t succeed in getting a woman to debase herself by having sex with you all that’s left are women who will sex with you in exchange for money.

Roger Dodger is much lighter than Mikey & Nicky, if only because it does not involve murder, hired killers or deadly betrayal and also because Eisenberg’s fawn-like charm has a way of cutting through the darkness. But the two films are similarly wise in their portrayal of how our society’s conception of masculinity turns men into misogynistic monsters who don’t seem to realize that their obsessive quest for sex without emotion or tenderness hurts them just as acutely as it does women they see only as prizes, conquests, rewards for being funny and smart and good-looking and clever and persistent and aggressive.

Roger Dodger was a hell of a directorial debut. I expected big things from writer-director Dylan Kidd, but in the ensuing 16 years, he’s only directed two theatrical motion pictures, once of which I remember quite liking (2004’s P.S with Laura Linney and Topher Grace) and the other I found utterly worthless, 2016’s long-shelved Get A Job. I similarly thought Roger Dodger would catapult Campbell Scott to A-list movie stardom. That didn’t quite happen either.

Of Roger Dodger’s principals, only Eisenberg has realized his extraordinary potential and he’s best known these days for playing super villains both real (Mark Zuckerberg) and fictional (Lex Luthor). Re-watching Roger Dodger, I was reminded why I found Eisenberg so charming and appealing at the beginning of his career. He delivers a terrific performance here characterized by a tricky combination of guile and guilelessness, calculation and aw shucks innocence.

The world has changed tremendously in the 16 years since Roger Dodger’s release in ways that have only made it timelier and more relevant and resonant.

If you’d like to make a Control Nathan Rabin 4.0 pledge, you can do so over at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace