Great Moments in Comedy: "Beautiful Ride" from Walk Hard

From the vantage point of 2018, it can be easy to forget what a massive cultural force Judd Aparow was for much of the aughts, as a writer, director, producer, mentor and one-man comedy factory.

For a while there, Apatow wasn’t just cranking out hugely successful and mostly pretty terrific comedies at a Fassbinder-like clip, he was making careers with everything he did. He wasn't just a producer and writer and director and mentor to the young people of comedy: he possessed the gift of fire, the ability to get movies made, and transferred it, Zeus-like, to disciples like Seth Rogen and James Franco and the rest of the young cast of Freaks & Geeks, almost all of whom went on to have careers as writers and producers and directors in addition to their often secondary acting careers.

Apatow wasn’t just a one-man industry pumping out comedies that became instantly iconic and made superstars out of his junior proteges; he was also running a makeshift comedy graduate school whose alumni include women like Lena Dunham and Amy Schumer, who have helped defined contemporary comedy and contemporary pop culture, for better or worse.

I am a fan of Schumer but have never seen any of her films because I think she promotes a poisonous ideology called "feminism" that encourages housewives to leave their homes and their husbands and experiment with lesbianism and witchcraft. As one of the leading lights of what’s known as the “Men’s Rights” movement, I am against that and in favor of entertainment that reinforces traditional gender roles and vigorously punishes—often through public spanking—any deviations.

So I choose not to see movies where Schumer displays her sinful body. It’s weird that I’ve never watched Girls because I have heard nothing but good things about Dunham and her comedy and her television program, especially among my men’s rights amigos, who are all, “Feminism is a cancer upon the face of white Christian society but Girls is a lot lot more conscious about issues of class and race and gender than it’s generally given credit for. It’s an examination of privilege, not an apologia for it. ”

In a seven year stretch Apatow produced, among many other, less successful film and television projects Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, The 40 Year Old Virgin, Talledega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, Knocked Up, Superbad, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, Step Brothers, Pineapple Express, Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Get Him to the Greek and Bridesmaids.

I don’t care if you’re a fan or not, and I happen to enjoy his movies a lot, and am up for seeing pretty much all of the above movies when they pop up literally every weekend throughout the basic cable universe as they inevitably do. They’re not all masterpieces, or movies that have changed the direction of comedy, as The 40 Year Old Virgin did, but they’re almost always re-watching or, in the case of Walk Hard worth re-watching and listening to.

In 2007, Apatow was at the height of his powers, creatively and commercially. Not everything he was successful, as evidenced by the presence of stinkers like Drillbit Taylor and Year One on his resume during this heyday but a lot of what he did connected in a big way that’s still being felt today.

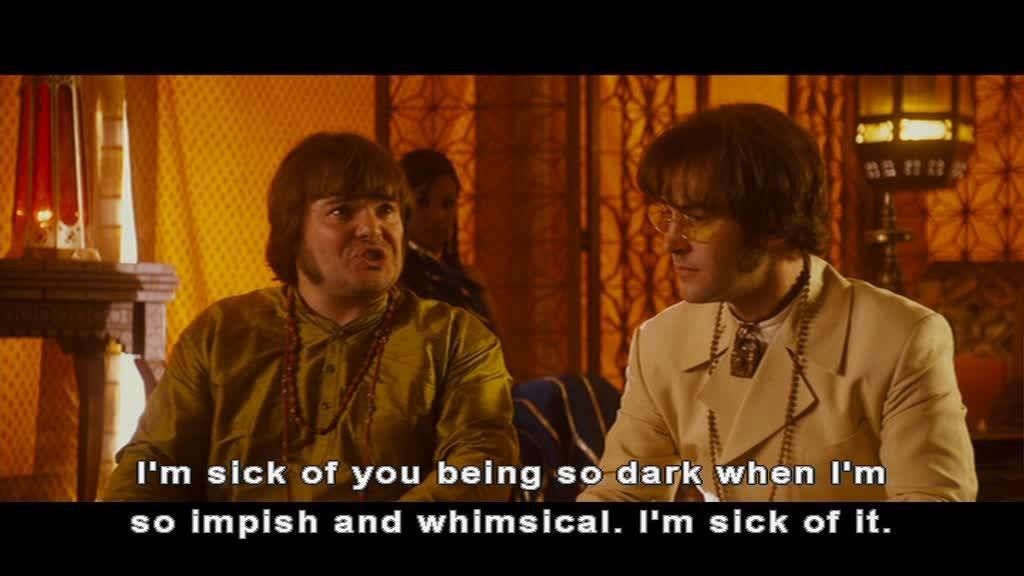

That’s certainly true of Walk Hard: the Legend of Dewey Cox. The film underperformed commercially at the time of its release, particularly for an Apatow production (he produced and co-wrote with director Jake Kasdan, son of Darling Companion screenwriter Lawrence) and for a film of its hype.

The studio pursued a risky promotional strategy for Walk Hard. They promoted the character of Dewey Cox—a gloriously larger-than-life amalgamation of Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Brian Wilson, Bob Dylan and myriad other legends who rocked and fucked and snorted their way to both glory and infamy—as much as they did the film. They wanted the audience to fall in love with Dewey Cox, its lovably degenerate anti-hero. They did but it took some time. Dewey might have died at the box office but he lives for eternity as a pop star, not unlike his contemporary Conor4Real in Popstar, another Apatow-produced instant cult classic of inspired pop culture pastiche.

The legend of Dewey Cox is inspired primarily by the enduring cult of Johnny Cash but its ambitions and its scope are bigger and broader than that. The film essentially sets out to lovingly lampoon the sum of the second half of the twentieth century in American music in a single overstuffed comic and musical extravaganza.

Miraculously, it succeeds, never more so than in its closing number, “Beautiful Ride”, where Cox, literally mere minutes from the sweet release of the grave, sings an anthem that summarizes everything he’s learned in four tuneful minutes.

He’s introduced, inevitably and perfectly, by Eddie Vedder, the ruggedly handsome face and trembling voice of Serious Rock Music, an exemplar of crunchy rock authenticity who has lent his somber presence to countless documentaries and tributes and adds the perfect note of solemnity to an introduction of Cox “performing his final masterpiece, that will sum up his entire life.”

He then returns to the stage a wizened old man, an elder statesman, a legend in the flesh returning to the stage after a prolonged absence for one final triumph. Reilly plays Cox as both a bumbling moron and a great, great man, a man who has attained true and lasting greatness despite being a bumbling man-baby.

We start on a note at once sonically intimate and thematically sweeping, with Cox reflecting against the primal scrape of an acoustic guitar, “Now that I have lived a lifetime full of days, Finally I see the folly of my ways” as that guitar is joined by the lonely whine of a slide guitar and then a sweeping arrangement lifting things effortlessly to the heavens.

With death literally minutes away, this wised-up former man-child is suddenly able to look back at his life, his triumphs and his tragedies from a God’s eye view, methodically dispensing pearls of wisdom, nuggets of truths that collectively add up to the meaning of life and one ridiculously over-achieving comedy song from a ridiculous movie that, honestly, has me weeping copiously in the McDonald’s where I’m writing this article. Yeah, I hang out sometimes at McDonald’s for the free wi-fi but I try not to brag about my lifestyle because I don’t want people to be jealous.

I wonder if I have a ridiculously outsized reaction to “Beautiful Ride” because my stupid baby animal brain loves Walk Hard so much that it secretly believes that Dewey Cox was a real man and that this was his actual heartbreaking, heartstrings-tugging, big screen Cinemascope final magnum opus.

Since Cox represents pretty much every rock legend from the early days of Sun records, I suppose when I mourn the ridiculous cartoon character of Dewey Cox I’m also mourning all the icons that went into his creation, your David Bowies and Johnny Cashes and whatnot.

In its own goofball way, there’s something almost hymnal about “Beautiful Ride”, something sublime and even transcendent about its epic sweep and desire to say everything that needs to be said about how to live a meaningful life in just a few minutes.

There’s a brilliant sort of meta joke that a man like Cox, who spent his life behaving like a drugged-up maniac, would end his existence standing on a stage in front of an adoring audience and disseminating profound existential truths through song.

But that’s the curious magic of the degenerate idiot savants we elevate to the level of Gods: One minute they’re accidentally destroying whole forests via the magic of fire in a doped-up delirium; the next they’re figures of Old Testament authority gloomily imparting wisdom to their adoring public.

One of the many things I’ve learned over the course of writing The Weird Accordion to Al is that a comedy song does not need to be hilarious, or even funny, to be great. “Beautiful Ride” is not a laugh out loud funny song.

But if there is a surprisingly effective dearth of hard jokes in the song itself there are a whole mess o’ inspired gags in the way Kasdan stages the performance, intercutting to flashbacks of things that either never happened or aren't in the film, and cutting to characters from over the course of Cox’s life and career, some of whom end the performance in a different state of existence than when they began. They die, and join the literal ghosts watching Cox put on one last unlikely master class before he joins them in rock and roll heaven, where the heroin is always pure and there’s no such thing as “underage” when it comes to groupies.

“Beautiful Ride” It’s a motherfucking anthem, is what it is. It’s words to live by, to tattoo on your chest. They’re words I personally try to live by.

I remember listening to that “Always Where Sunscreen” song Baz Luhrmann produced for my Now That’s What I Call Music! project and was surprised and a little alarmed to see so much truth and wisdom in the song’s banal, cliched words. The older I get, the more truth I see in cliches and the less point I see in denying them, particularly when they are executed as elegantly as they are here.

“Beautiful Ride” offers not just words to live by, but words to die by as well.

“Beautiful Ride” accomplishes the seemingly impossible feat of joining the small but impressive pantheon of epic life-summarizing ballads it’s simultaneously spoofing and paying rapturous tribute to. I’d put it up there with “My Way” and “In My Life” and other songs that attempt to say everything there is to say about life and being a man and an artist within the sometimes elegant but inherently insufficient vehicle of the pop song. It’s a loving and pitch-perfect pastiche of the life-summarizing magnum opus that just so happens to be a sneakily brilliant and convincing life-summarizing magnum opus in its own right.

Y’all know the deal: I make most of my living from the Patreon, man, so if you would throw me a couple of nickels over at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace that’d be groovy.