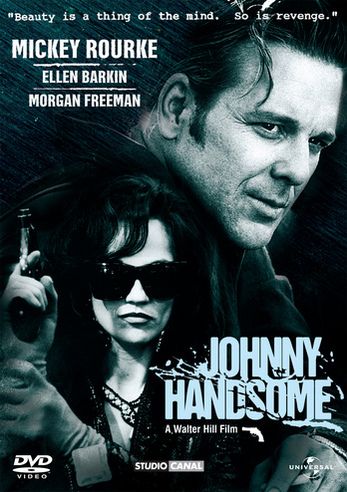

Control Nathan Rabin 4.0 #37 Johnny Handsome (1989)

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the site and career sustaining column where I give you, the kind-hearted, philanthropic, Christ-like Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch, and then write about, in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to 75 dollars with each subsequent choice.

The woman who chose Johnny Handsome saw it at the tender and, I would argue highly inappropriate age of nine. She thought it was the worst movie she’d ever seen, although unless she was a precocious young cinephile I’m not sure how much formidable competition it had at that point. A nine year old’s frame of reference for bad movies, and anything else really, for that matter, is inherently going to be smaller and more subjective than a forty-two year old’s, if I might pick an age at random that I happen to be.

The patron grew up to discover, to her surprise, that the film has its defenders and champions who see it as a nifty neo-noir from a master of the form. I’m something of a Walter Hill fanboy so I dug Johnny Handsome when I saw it during its theatrical release in 1989, I dug it when I re-watched it on video and I liked it all over again when I saw it again for this column.

But I can understand how a child, a literal child, might look at Walter Hill’s moody meditation on fate, second chances and physical and moral ugliness and see a laughably over-the-top camp riot impossible to take seriously.

For starters, Johnny Handsome pushes Mickey Rourke’s marble-mouthed method Marlon Brando mumbling to such extremes that it can be very hard to understand what he’s saying when his speech is impaired by physical disfigurement from birth and even after he’s made beautiful and his speech impediment mostly disappears.

In a way, the patron considering Johnny Handsome the worst movie they’d ever seen represents a form of backwards praise. It means that the movie made an indelible impression on her, that it stamped itself onto her consciousness as the worst of the worst, cinema’s true nadir, the standard against which all future cinematic abominations would be judged. Best/worst, they’re two sides of the same coin. They both make intense impressions.

I can see how Johnny Handsome might make such a striking impression on a suggestible young mind. It has the spooky, archetypal feel of a hard-boiled, neo-noir fairy tale about a brutal beast of a man who is made beautiful by kindly helpers, only to fall victim to the ugliness in his soul and an all-consuming hunger for revenge that takes precedence over more honorable emotions and ambitions. Alternately, it has the pleasantly disorienting vibe of a waking dream.

Adapted from The Three Worlds of Johnny Handsome, a novel by John Godey, who also wrote the novel that inspired The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Elliott Kalan’s favorite movie, Johnny Handsome casts Mickey Rourke as John Sedley, a man who turned to a life of crime after being born disfigured.

He’s the hate that hate made, an angry, small-time hood who goes in on a job with old pal Mikey Chalmette (the great character actor Scott Wilson, making the most of his very limited time onscreen) despite their scumbag accomplices (Ellen Barkin breathing fire as prostitute turned femme fatale Sunny Boyd and Lance Henriksen as Rafe Garrett, a non-blood-drinking version of the iconic country bloodsucker he played in Near Dark) doing a very bad job of hiding their eagerness to kill their co-conspirators at the first possible opportunity.

A good rule of thumb for criminal lowlifes in movies like these is that if someone insults your looks repeatedly and seems eager to murder you as soon as it becomes convenient and lucrative to do so, you should not go into business with them, especially a life-and-death endeavor like armed robbery.

Alas, Rourke’s cursed hood doesn’t have more appealing options, so he just barely survives a botched robbery that leaves Mikey dead. Johnny is not a good man yet he nevertheless receives the opportunity of a lifetime when a big-hearted doctor played by a young Forest Whitaker decides to give the luckless career criminal a new face, a new name, a new history and a new life working on an honest job.

You can take the man out of the underworld, alas, but you can’t take the underworld out of the man. Though Johnny strikes up a tentative romance with a company bookkeeper played by Elizabeth McGovern he wastes no time blowing the chance to go straight by dreaming up a big-money, big-danger heist that will finally allow him to get revenge on Sunny and Rafe for killing what appears to be his only friend.

Before he was very lucratively typecast as God and various God-like figures, Morgan Freeman was brilliant at playing devilish bastards like Johnny Handsome’s Lt. A.Z. Drones, a cynical lawman who correctly sizes up Johnny as someone whose criminality goes much further than skin-deep.

Hell, Freeman got nominated for an Academy Award for Street Smart despite playing a vicious pimp in a goddamn Cannon movie. He’s similarly sly and savvy here playing a demon hovering over our anti-hero’s shoulder, reminding him that he’s a criminal and a hood destined for a bloody, tragic demise no matter what his face looks like or how much misplaced faith his benefactors might have placed in him.

Committing crimes isn’t something Johnny does because he lacks better, less criminal options. It’s who he is as a human being. No amount of cosmetic surgery can possibly change that. The nice doctor who fixes Johnny’s face and the nun who gives him encouragement might like to imagine otherwise, but Johnny’s fate has already been sealed. This is one crook who defiantly refuses to be rehabilitated.

There is no salvation in the world of Johnny Handsome. There is no redemption. Rourke gives the movie’s doomed anti-hero a powerful internal quiet, even gentleness, that never quite masks the brutality at his core. The moment Rourke sees his new, beautiful face he exudes a guileless, child-like joy at finally being freed from the prison of looking like a monster but he’s too far gone to ever be able to live a straight life. Honest lives and jobs mean nothing to men like Johnny with vengeance and larceny in their souls.

Barkin and Henriksen are not subtle in their villainy. Metaphorically speaking, Barkin’s scheming opportunist has blood dripping from her fangs. She exudes pure evil. She’s all raw, dangerous sexuality, greed and naked calculation. Henriksen is similarly volcanic as a wild-eyed sociopath with murder in his soul. There’s goodness and gentleness in Johnny to go along with all the anger, rage and violence but there does not seem to be an iota of good in any of the thieves, hoods and murderers Johnny is doomed to call contemporaries.

Time has a way of turning all beauties into beasts. Women get it worst by a huge margin, as always, but time has been particularly cruel to Rourke in no small part because he was exceptionally handsome as a young man. He wasn’t just handsome: he was beautiful. In his radiant prime (think Body Heat or Diner), Rourke had a very Brandoesque combination of macho brutality and feminine beauty.

Johnny Handsome makes inspired use of both the sensitivity and the savagery at Rourke’s core. Seeing Rourke play a man who goes from beast to beauty is a surreal and deeply sad experience in 2019 considering that Rourke now looks more like pre-surgery version of his character in Johnny Handsome than the post-surgery version.

Walter Hill’s grubby crime paperback of a B-movie can be campy and mannered and over-the-top but there’s a resonant sadness at its core rooted both in Rourke’s trajectory as an actor and man and the film’s deftly handled fatalism. It’s a sad movie about a sad man who cannot escape a sad fate from a master of neo-noir operating at the peak of his abilities.

Johnny Handsome is at once a modest yarn and a movie interested in lofty issues of fate and destiny and rehabilitation that holds up nicely three decades on largely because its visual and thematic aesthetic is based in the style and sensibility of classic noir and hardboiled 1950s fiction rather than the hideous fashions of the late 1980s, which were monstrous in their own right. Hell, the hair helmet that Barkin rocks here is so stiff with hairspray that it could seemingly deflect bullets.

Speaking of noir and retro stylization, Johnny Handsome reminded me at times of the hardboiled side of Tales from the Crypt. That shouldn’t come as a surprise considering that Walter Hill was working on the iconic HBO anthology around this time as both an Executive Producer and occasional director, including a memorable episode with Henriksen as a psychotically driven gambler. I mean that as high praise rather than criticism: Johnny Handsome is a lurid, vulgar, B-movie pulp with panache. That’s precisely what I love about it.

If you’d like to participate in this column you can do so over at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace .