First and Last: John Singleton Boyz N The Hood (1991) and Abduction

It can be easy to forget what a seismic cultural event 1991’s Boyz N The Hood represented. It wasn’t just a movie: it was a pop culture phenomenon, a game-changer that proved conclusively that it was possible for a realistic movie with integrity about the struggles of black America to make a whole lot of money while articulating a socially conscious message aimed at both white and black America.

Writer-director John Singleton’s revered debut has played such a crucial role in the evolution of African-American filmmaking that the history of black film can reasonably be divided into two categories: pre-Boyz N The Hood and post-Boyz N The Hood. Boyz N The Hood led to the rise of the “hood movie,” a boom in black independent filmmaking with roots in both the lurid, violent, sexed-up sensationalism of blaxploitation and in the socially conscious ambition of Singleton and Spike Lee.

Boyz N The Hood wasn’t just received as a debut of astonishing raw power and intensity: it became news. Though it is a fictional narrative film, it was received almost as if it were a documentary or a docudrama, as a brutal and lyrical slice of life with much to teach black and white audiences alike about the socioeconomic realities of being black and young in gang-ravaged South Central L.A.

Singleton, who died much too young at fifty-one, was one of American film’s true wunderkinds. In an astonishing feat of precocity, he was filming Boyz N The Hood at 22 and became a two-time Oscar nominee for Best Director and Best Screenplay at 24. Singleton certainly directs Boyz N The Hood with the urgency, energy and conviction of a young man.

Like S.E Hinton when she wrote The Outsiders and George Lucas when he wrote and directed American Graffiti, Singleton’s portrayal of teenage life gained a bracing sense of verisimilitude from its creator essentially being a kid himself. When he started shooting the film that would make his reputation and change black film forever, Singleton was just a few years removed from being a teenager so the experience of being young and frustrated and overflowing with hormones and emotions and anger was still fresh in his memory.

Future professional goofball and Boat Trip funnyman Cuba Gooding Jr. cuts an uncharacteristically dignified figure as Tre Styles, a young black man growing up hard in South Central under the watchful eye of single father Furious (Laurence Fishburne, burning with righteous intensity) and mother Reva (Angela Bassett), a strong, dignified professional who nevertheless has her son live with her father under the logic that only a man can raise a man. Despite Bassett’s fierce, loving and powerful performance that notion was regressive and more than a little sexist at the time of the film’s release; it hasn’t become any more progressive in the ensuing years.

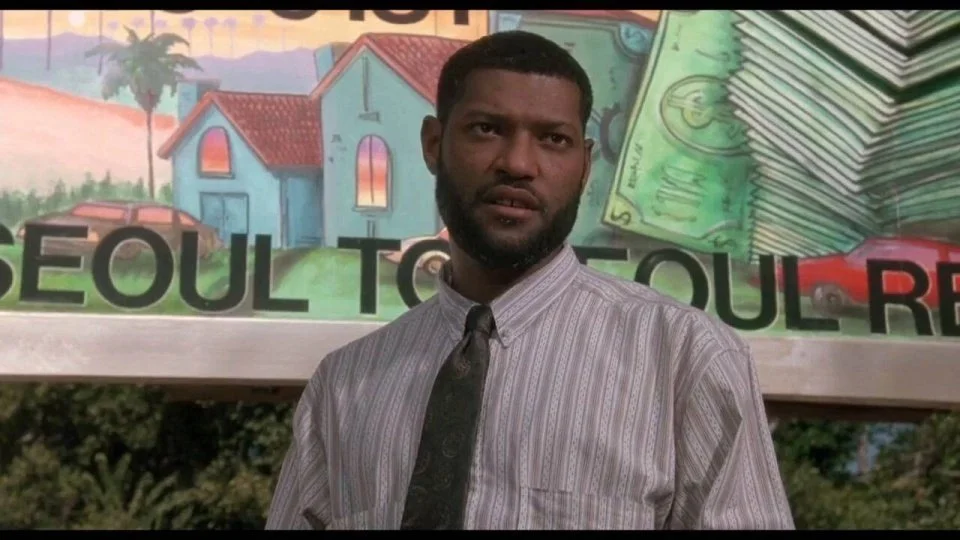

Fishburne is such a magnetic, explosive performer that he can loftily inhabit the role of the Soul of Black America and spend much of his time onscreen pontificating loftily about the nature of the black man in America and still register as a fiery, flesh and blood human being, not just a soapbox for Singleton’s ideas.

The chemistry between Gooding Jr. and Fishburne forms the film’s emotional core. If Gooding Jr. cuts a bracingly serious, even somber figure here as opposed to the flailing, mugging cartoon character he would go on to play in comedies that’s partially because a titanic, proud and idealistic figure like Furious Styles would not tolerate that level of foolishness from his flesh and blood.

Boyz N The Hood is one of the most powerful portrayals of paternal love in the history of American film. As a part of an ideology steeped in social conservatism, the film is, at its core, a love letter to strong black fathers as well as an ode to responsible gun ownership and black capitalism, which it presents as the salvation of America’s inner cities.

Singleton’s shatteringly powerful drama is fundamentally about a father who, through sheer force of will and deep, abiding love, saves his son from the deadly temptations of life in the hood not by coddling him but by giving him the inner strength, discipline and love for self that allows him to survive the perilous crucible of growing up in a war zone.

In his breakthrough role Ice Cube, who had just left NWA and was establishing himself as one of rap’s most incendiary and important provocateurs, is electric and alive as Doughboy, a gun-toting drug dealer and small-time criminal whose brusque demeanor and bleak fatalism can’t entirely hide a lyrical bent. Throughout the film we get tantalizing glimpses at the sensitive, poetic soul Doughboy might have been if he’d grown up in a place that nurtures and rewards openness and vulnerability instead of punishing them.

Morris Chestnut rounds out the leads in a similarly star-making turn as Ricky, a jock and star athlete who think athletics and a college scholarship are his way out of the hood, or possibly a character-building stint in the Army. He doesn’t realize that for some doomed souls escape simply is not possible no matter how badly you might long to get out.

Singleton’s rightfully revered debut is an emotionally authentic portrayal of what it’s like to be young and angry and confused so it’s at least partially about horny, rebellious teenagers’ attempts to get laid. Even at 22, Singleton was prematurely wise enough to realize that he did not have to choose between making a movie about teenagers’ attempts to get laid and making an important motion picture about the state of black youth in our nation.

Singleton understood that everything was inextricably intertwined, that he could make an important statement about the state of black youth through the story of their feverish attempts to get laid, of course, but also to understand themselves and their families and friends and futures and everything else that comes with coming of age, then, now and always.

In Boyz N The Hood the grim specter of violent death haunts every interaction, no matter how casual or joyful. It casts a long shadow every barbecue, every party, every lazy Friday evening spent hanging out and trying to get into trouble.

Boyz N The Hood was universal in its heart-wrenching depiction of coming of age in a society that doesn’t want you to succeed, or even survive, but it also benefits from cultural specificity, like the background roar of police helicopters that serve as an ever-present reminder of police surveillance.

Singleton became an instant auteur articulating the angst and joy and desperate yearning of communities that were invisible as far as Hollywood was concerned. From a geographical perspective, the bullet hole riddled streets where the existentially despairing young men of Boyz N The Hood come of age and/or die weren’t too far from Hollywood studios but they were a million miles away in terms of race and class.

Boyz N The Hood shook the conscience of white and black America alike. White people are relatively absent here with the exception of a teacher and cop who says little while his black partner terrorizes multiple generations of Styles men in explicitly racist, self-hating terms. So Singleton’s emphasis is on black on black violence from the first frame to the last.

Singleton told the stories of people who had never seen themselves and their lives onscreen before, let alone rendered with such power, authenticity and compassion. He told them with such humor, heart and drama that everyone could see themselves in the struggles of these beautiful young men, even people who might be tempted to judge them based on the color of their skin, the music they listen to, and the neighborhoods they live and die in.

Singleton’s first film was a tremendous gift not just to an American film landscape that did not realize just how desperately it needed it, and films to follow like Juice and Menace II Society, but to the public as a whole. It wasn’t just an assured, exciting, suspenseful and ultimately tear-jerking piece of entertainment; it served as a call to action to an apathetic populace as well as the inspirational first shot in a black filmmaking revolution whose aftereffects are still being felt today.

Singleton’s too brief career had three distinct phases. First and foremost there was the cultural Big Bang of Boyz N The Hood and then a series of ambitious, deeply personal auteurist efforts that explored the complexities and pain of the black experience from a series of different perspectives.

1993’s Poetic Justice is the quintessential messy, alive, ferociously ambitious and flawed follow-up, a dewy romance pairing Janet Jackson with Tupac Shakur. 1995’s wildly overreaching college message movie Higher Learning was, if anything, even messier, even more alive and even more ferociously ambitious and flawed while 1997’s overreaching and impressive Rosewood was a historical drama about the real-life 1923 Rosewood Massacre.

Singleton’s final movie as an auteur was another messy, electric personal film, 2001’s Baby Boy, a follow-up of sorts to Boyz N The Hood that once again shone a life on the complicated emotional lives of young black men in contemporary Los Angeles.

By that point Singleton had already made his first big action movie: the 2000 reboot Shaft. That kicked into gear the second phase of Singleton’s career, as a director for hire on action movies like 2003’s 2 Fast 2 Furious, 2005’s Four Brothers and finally 2011’s Abduction, an astonishingly stupid vehicle for oft-shirtless male starlet Taylor Lautner, who won the hearts of teenyboppers everywhere as the werewolf third of Twilight’s sizzling supernatural love triangle and lost them with everything he’s done since.

The final phase of Singleton’s career involves his shift to working primarily in television in the final decade of his life on acclaimed fare like 30 for 30, Empire, American Crime Story and Billions.

It’s easy to understand why Singleton might want to take a break from the big screen if Abduction was the kind of material he was being offered as a filmmaker.

Abduction presented Singleton with a formidable challenge, if not a downright impossibility: making the werewolf guy from the Twilight movies a movie star who can comfortably carry an action thriller and not be blown offscreen constantly by a cast full of ringers like Sigourney Weaver and Alfred Molina.

Alas, Abduction proved one of those unfortunate situations where a featherweight pretty boy with no business starring in a movie is given a role even an actor capable of expressing emotions would find impossible to play convincingly.

Lautner plays Nathan Harper, the movie’s protagonist, as a teenage idiot beefcake version of Jason Bourne, a jock dolt who spends his high school years begging for death by riding on the outside of a speeding truck, playing beer pong and passing out blackout drunk at raging keggers but displays Chuck Norris-like agility and fighting skills after he discovers that his entire life has been a lie and that the people he thinks are his parents are actually secret agents.

The simian-jawed teen idol begins the film leading the carefree life of a high school party animal. All he has to worry about is his suspiciously hard-ass father figure Kevin Harper (Jason Isaacs) insisting they put on some pads and beat the crap out of each other in the backyard, almost as if the older man is trying to train the younger man for some strange destiny he cannot envision.

Then one day our dim-witted hero and Karen Murphy (Lily Collins), the cute girl he has a crush on, are assigned to do a report on missing children. The attractive youngsters access the internet and discover a missing child who sure seems to have grown up to be Lautner. What are the odds?

Abduction has an adorably naive, wonderfully and painfully dated conception of computers and the internet as magical entities of limitless power. It’s the kind of movie where the heroes enter a chat room, which pings a hacker half a world away, which then brings them to the attention of the CIA.

That would feel anachronistic back in the totally 1990s days of The Lawnmower Man and The Net. It feels downright prehistoric in a movie from 2011.

Nathan and Karen go on the run in a bid to avoid sinister CIA operative Burton (Alfred Molina, collecting a paycheck) and sinister cold-blooded killer Kozlow (Michael Nyqvist). Along the way they investigate the mystery of Nathan’s true identity, particularly in regards to his real father.

The script for Abduction somehow made the 2010 Blacklist of best un-produced screenplays but the action is so insultingly preposterous that Singleton might have been better off leaning into the absurdity and campiness of its La Femme Nikita-for-jock-idiots premise and playing up the pulpy B-movie aspects rather than trying to generate real drama, emotion and suspense out of a screenplay that angrily demands suspension of disbelief but offers nothing in return. We cried for the doomed young men of Boyz N The Hood. It would be foolish to waste emotion on these cartoon characters.

Singleton and Lautner play things extremely straight, which ensures that the laughs are of the unintentional variety. Abduction does not have a sense of humor about itself, which helps explain why it’s unintentionally funny throughout.

Abduction was supposed to prove that Lautner could carry a movie by himself, that he didn’t need a huge cultural phenomenon like Twilight or the more charismatic likes of Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart, both of whom have gone on to tremendous careers post-Twilight, to make a movie people would want to see. Instead Abduction and its even more poorly received follow-up, the 2015 parkour-flavored action thriller Tracers, proved the opposite.

Abduction would benefit from a young Matt Damon type as its lead; instead it stars someone more realistically cast as the glowering bully who beats up the Matt Damon type and tries to steal his girlfriend.

Lautner did most of his own stunts here, which is impressive. Alas, he did ALL of his own acting, which is less impressive. Whether he’s grappling with family drama or outwitting secret agents twice his age and intelligence Lautner is perpetually unconvincing, eternally defeated by whatever melodramatic nonsense the film has in store for him.

Singleton began an impressive if much too short career with a ferociously alive, incontestably important message movie that illustrated that Ice Cube was just as explosive and undeniable a force on the big screen as he was on wax.

Like far too many great filmmakers, Singleton ended his career on a down note, with a movie that asked audiences to pay good money to see not just a movie with Taylor Lautner in it, but a Taylor Lautner movie. The public had no difficulty rejecting that particular proposition. Lautner’s smoking hot physique may put the “ab” in Abduction but Singleton’s dispiritingly impersonal and generic final film showed that some people are just not meant to be movie stars, Taylor Lautner chief among them.

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

AND of course you can also pledge to this site and help keep the lights on at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace