Control Nathan Rabin 4.0 #259 Nixon (1995)

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the career and site-sustaining column that gives YOU, the kindly, Christ-like, unbelievably sexy Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch, and then write about, in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to seventy-five dollars for all subsequent choices.

Or you can be like four kind patrons and use this column to commission a series of pieces about a filmmaker, actor or television show. I’m deep into a project on the films of the late, great, fervently mourned David Bowie and I have now watched and written about every movie Sam Peckinpah made over the course of his tumultuous, wildly melodramatic psychodrama of a life and career. That’s also true of the motion pictures and television projects of the late Tawny Kitaen.

A generous patron is now paying me to watch and write about the cult animated show Batman Beyond and I just finished a look at the complete filmography of troubled former Noxzema pitch-woman Rebecca Gayheart. Oh, and I’m delving deep into the filmographies of Oliver Stone and Virginia Madsen for you beautiful people as well.

As readers of this site are well aware, I am a man of many obsessions. Indeed, Nathan Rabin’s Many Obsessions would be a fine alternate name for Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place.

Richard Nixon is one of my myriad fixations. He was the most human of American presidents, and consequently the most fascinating and relatable.

From famously modest origins, Nixon became a Senator, then a two-term Vice President before getting elected to the highest office in the land twice. That is a staggering amount of success yet through it all Nixon somehow managed to maintain an image as a sad, sweaty, pathetic loser who nobody liked.

Tequila!

For a consummate loser, Nixon sure seemed to win a lot yet for a man with extraordinary, historic achievements he never stopped seeming like a luckless, hopeless, self-defeating schmuck.

Is it any wonder that I identify deeply with this miserable man? I identify with Nixon’s class resentments, his loneliness, depression and anxiety as well as his sense that he would never be good enough.

It seems safe to assume that Oliver Stone is obsessed with Nixon as well. Nixon reigned as the preeminent bogeyman of the 1960s countercultural, the very personification of Conservative corruption yet in Nixon Stone depicts Nixon in a surprisingly empathetic, if not heroic light.

Stone makes Nixon a historical horror movie, Presidential Noir. He depicts the disgraced ex-President as a Frankenstein’s Monster of a politician, at once horrifying and deeply sad, a monster to be sure, but also one in tremendous, almost inconceivable pain.

Nixon opens with the words, “This Film is a Dramatic Interpretation of Events and Characters Based on Public Sources and an Incomplete Historical Record . Some Scenes and Events Are Presented as Composites Or Have Been Hypothesized Or Condensed.”

That’s a not particularly subtle way of saying that they made a bunch of shit up wholesale when it suited their purposes. Stone has an adorable habit of establishing, then re-establishing the themes of his films over and over again, until even the slowest audience member knows exactly what he’s trying to say.

For example, it is, in fact, possible to ascertain that Nixon is the story of a man who gained the world but lost his soul by the fact that the opening disclaimer is immediately followed by the bible quote, “For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his soul?”

Nixon is not subtle. It’s not understated. Stone does not bring a light touch to the material. But for once the material suits Stone's pulpy, maximalist aesthetic. Nixon is one of Stone’s best and deepest films largely because of its innately compelling subject.

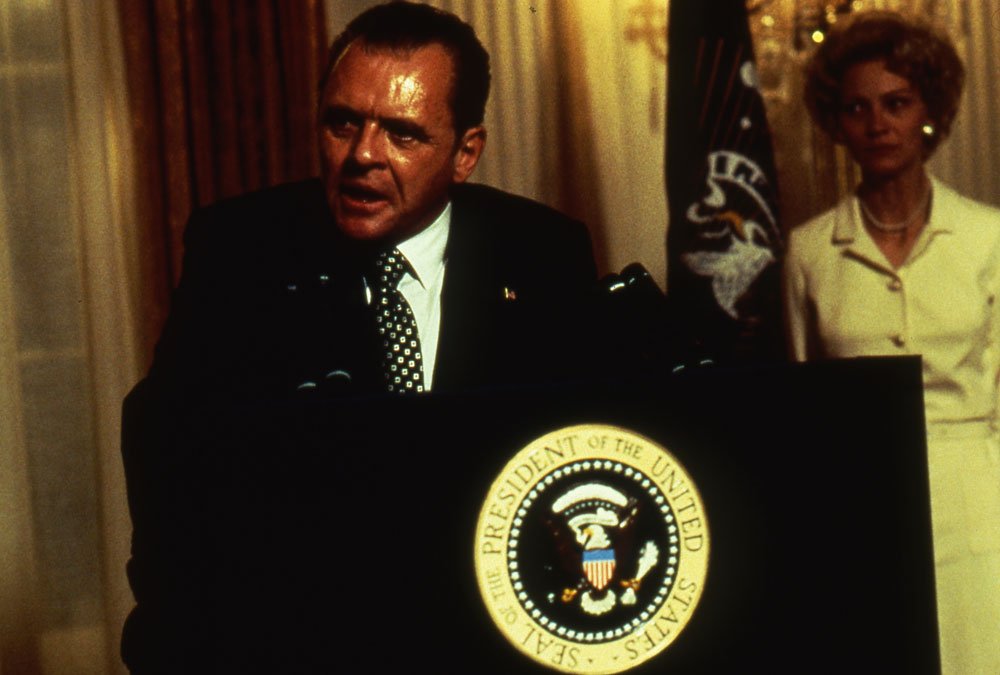

In an unconventional but inspired bit of casting, the very British Anthony Hopkins plays the very American Richard Nixon as a man of constant sorrow who perpetually looks both constipated and like he just accidentally ate something unbearably bitter and sour.

They have fun!

Stone and ace cinematographer Robert Richardson depict Nixon as a figure of shadows thematically and visually. In the first act of a one hundred and eighty nine minute epic, Hopkins is frequently shot in near total darkness from extreme, distorted angles, like a hunched-over fiend who recoils from sunlight, light and warmth.

He is a cursed creature born of suffering and loss, to a failure of a father and a stern, bible-thumping mother (Mary Steenburgen), who put the fear of god in her earnest, melancholy child and didn’t stop until she filled his suggestible young mind with dread and self-loathing.

Nixon is close with his mother in much the same way that Norman Bates is close with his ma. Nixon’s young life is shrouded in tragedy. He lost two brothers to Tuberculosis and his father died poor and bitter.

Even Nixon’s successes are rooted in failure and humiliation. He successfully wooed the iron-willed Pat (Joan Allen) and won her hand in marriage, but only after first chaffering her on dates with other boys.

“I am disgusted by you and everything you represent, you hollow, empty shell of a man” is the subtext of every exchange between the ambitious politician and his long-suffering wife although it’s frequently text as well.

Throughout the film’s first act, people never stop telling Nixon that he fucking sucks and is a colossal tool, often, if not invariably, to his face.

Stone really piles on the humiliation. He stops just short of adding ADR to the end of each scene of an anonymous voice hissing, “Man, does that Nixon guy ever suck! What a fucking loser.”

Of course plenty of people hated Nixon in his lifetime. Yet it nevertheless often feels like the characters are responding, with visceral, overwhelming disgust not to the sad man in front of them but rather to the Nixon of the historical record, who resigned from office in disgrace rather than risk going to jail and is now synonymous with failure and public humiliation.

Hopkins makes Nixon masochistic and pragmatic enough that he more or less accepts being continually insulted, belittled and emasculated by seemingly everyone around him, from his wife to his political colleagues to the press, as a steep but acceptable price to pay for attaining such incredible, undeserved success.

Stone skips Nixon’s many victories in order to focus monomaniacally on his many crushing defeats. He’s all ambition and ruthless guile and cynical calculation unmoored from ethics or integrity, a hollow man who sought ultimate power and control at any cost because he felt utterly powerless in his personal life.

For this ramble through Nixon’s life, times and crimes Stone has assembled what can genuinely be deemed one of the greatest casts of the past fifty years. In addition to Hopkins and Allen, Nixon stars James Woods, J.T Walsh, Paul Sorvino, Powers Boothe, E.G Marshall, David Paymer, David Hyde Pierce, Tony Goldwyn, Kevin Dunn, Saul Rubinek, John C. McGinley, Fyvush Finkel, Ed Harris, Madeline Kahn, Robert Beltran, Bob Hoskins, Edward Herrmann, Dan Hedaya, Tony Lo Bianco, Annabelle Gish and Larry Hagman.

Hell, even George Plimpton shows up late into the proceedings. It’s a murderer’s row of great character actors playing cold-blooded opportunists who will do anything to attain and hold onto power.

Hoskins is appropriately terrifying as J. Edgar Hoover and Boothe is a force of nature as a power-mad Alexander Haig while Pierce delivers his finest film performance as John Dean, the conscience of the film and the Nixon administration.

Propped up by sinister businessmen with decidedly impure motives, Nixon keeps failing upwards until Watergate causes everything to come crashing down around him and he becomes an American King Lear, a half-mad monarch terrified of a world he no longer understands.

As its subject spirals further and further into madness Stone’s delirious psychodrama becomes increasingly abstract and free-associative. It goes so deep into Stone’s obsessions and recurring motifs that I half-expected Nixon to commune with a Native American shaman and rock out at a Doors concert.

Nixon illustrates that sometimes the saddest, darkest and loneliest place in this whole miserable nation is The White House. Part of what makes Nixon so compelling are the Trump parallels.

Trump may ostensibly be a handsome winner born into wealth and privilege and coddled throughout his sheltered existence while Nixon came from nothing and was ugly, sweaty and unappealing but they share a hatred of elites and the establishment and a populist conviction that they, and they alone, represent the common people who make our country great, the Silent Majority and MAGA mob.

In that respect Nixon feels like it’s about Trump and his uniquely American madness as much as it is its title character.

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!