The Movie Mad 1971 Oddity The Projectionist is Notable for Reasons Beyond Rodney Dangerfield's Debut Performance

1971’s The Projectionist belongs to the curious, scrappy subgenre of movies about movies that are partially made up of other movies. Like the hilarious blaxploitation parody Black Dynamite, Allan Arkush and Joe Dante’s ingenious exploitation spoof Hollywood Boulevard and Tom Schiller’s lovely comic fantasy Nothing Lasts Forever, The Projectionist combines original footage with excerpts from a dazzlingly diverse array of movies from throughout the decades.

This lends the film an undeniable split personality. On one level, The Projectionist is a grubby, scrappy, very 1970s independent film full of atmospheric, documentary-style footage of sweet-faced, toddler-bodied protagonist Chuck McCann walking glumly through the bustling, impersonal streets of Manhattan like a doughier, more benign Travis Bickle. On another, it’s got all the production values in the world, since it does things like “sample” the lush melodramas of Humphrey Bogart (incorporating selectively edited selections of footage from the icon’s work into its own story) with the aggressiveness and shamelessness of a Golden Age Hip Hop producer recycling James Brown’s pioneering grooves.

Bogart is only one of a series of icons gracing The Projectionist thanks to the magic of constructive editing; Orson Welles and John Wayne show up, as does Hitler and just about anyone and everything else writer, director, co-star and editor Harry Hurwitz can fit into his simultaneously over-stuffed and under-written tribute to Hollywood’s Golden Age. The movie’s “stars” are huge and many. Its actual cast is a lot more modest but impressive in its own right.

Star Chuck McCann, ostensibly playing himself, the title role, was a popular children’s entertainer, voiceover artist, actor and impressionist, a talent that is given quite the workout here via his character’s compulsive need to trot out good if groaningly familiar impersonations of the legends of yore, your John Waynes and James Stewarts and whatnot. “Special Guest Star” Ina Balin, who plays the projectionist’s love interest in the elaborate homages to silent and French New Wave film that take up much of the film’s running time, was a popular and prolific actress with the distinction of being nominated for two separate Golden Globes for From the Terrace. She was nominated for both best supporting actress and most promising newcomer and won for promising newcomer.

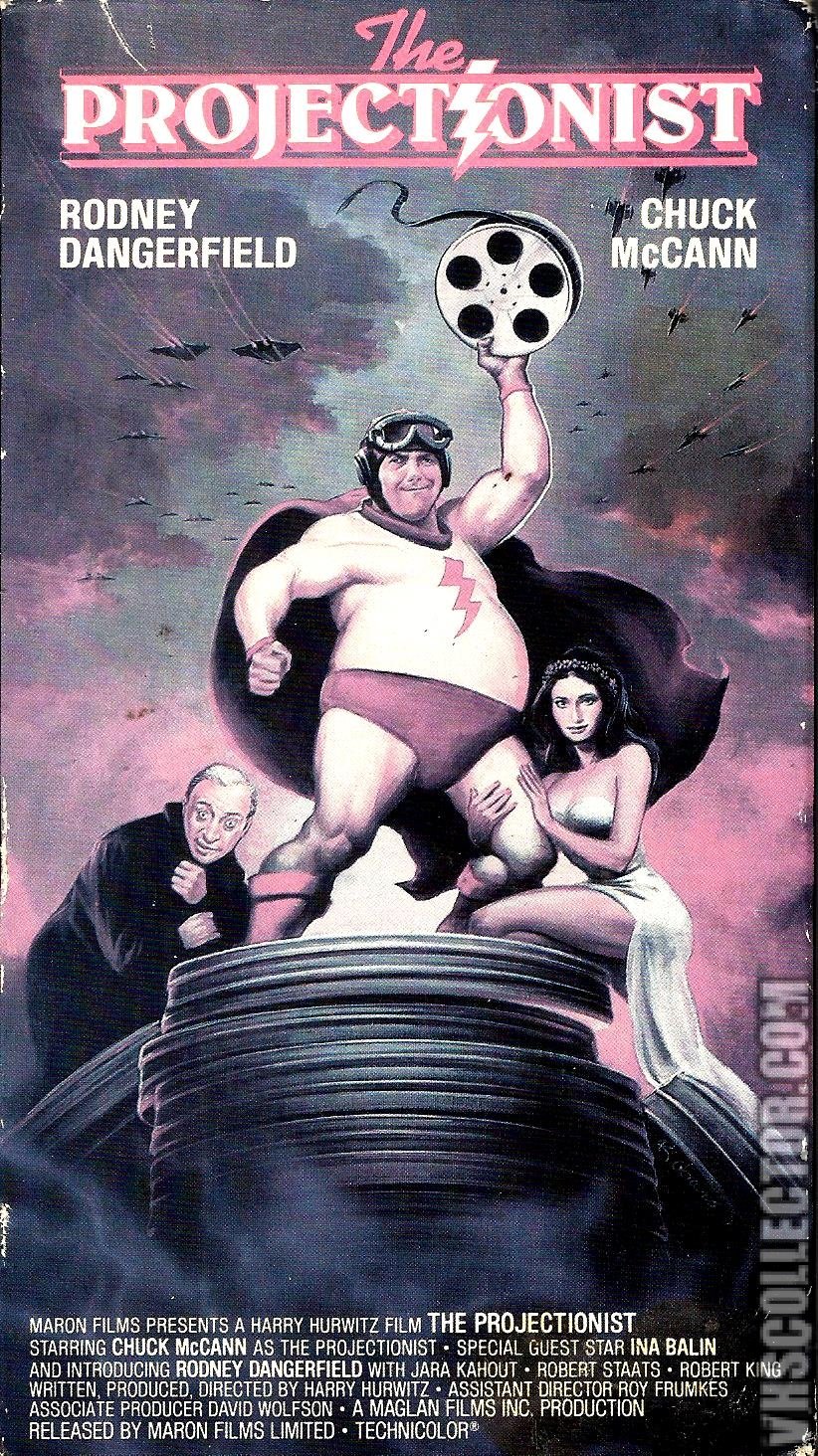

But the film’s most auspicious cast member, indeed its biggest claim to fame, somewhat famously had not earned that kind of respect from the industry. He was a struggling stand-up comedian named Rodney Dangerfield who made an indelible debut here in the dual role of Renaldi, the movie theater’s stern, authoritarian, Mussolini-like manager, and the Bat, an evil villain who squares off against the projectionist’s alter-ego Captain Flash, a silent movie serial hero in a deeply unflattering costume, in fantasy sequences.

When Rodney returned to the big screen nearly a decade later in Caddyshack, he had one of the most defined personas in comedy history. But when he made The Projectionist he was still a struggling, unknown stand-up comedian so the rhythms and inflections and vocal and physical tics and mannerisms that would soon be set in stone aren’t present. The Rodney we see here is one we’ll never see again, lending the film an intriguing element of novelty, particularly for students of comedy history.

The Projectionist marks one of the only times, if not the only time, when Dangerfield would play a character that had absolutely nothing to do with his stand-up act or his persona. In his later vehicles, Dangerfield wouldn’t really act: he did shtick. In The Projectionist, there is no shtick, just a surprisingly straight-faced character actor turn as a sad-eyed ball-buster who takes sour delight in abusing what little power he possesses.

This Dangerfield is also of course about a decade younger than the one that would win our hearts with Caddyshack but he’s still deep into middle age. If Dangerfield’s turn as Renaldi is uncharacteristically restrained, Dangerfield plays the The Bat with a hammy, theatrical bigness befitting a silent film bad guy.

Yes, there’s a whole lot going on in The Projectionist, and, paradoxically, not much going on at all. There isn’t really a story to speak of. The projectionist daydreams. The projectionist walks around. The projectionist walks around some more. The projectionist daydreams about being a hero and getting the girl. The projectionist’s daydreams are invaded by the heroes and villains of Hollywood past, just as he fantasizes about transgressing the barrier between his humdrum real life and the exciting world he projects onto that beautiful, beautiful movie screen.

The Projectionist is edited as much as it is written or directed, if not more so. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that many, if not most, of the key creative decisions were made in the editing booth, where the instantly recognizable and utterly obscure of our shared cinematic past mix and mingle and intertwine to create wild and weird new mutations.

In a sense, the movie and pop-culture mad Hurwitz was doing, within the context of a narrative comedy, what Joe Dante was doing when he stitched together commercials and serials and everything else that captured his manic and fertile imagination into 1968’s The Movie Orgy, a free-flowing stream of consciousness proto-mash up that at its longest ran some seven and and a half hours, or enough for a good-sized LSD trip.

With The Projectionist and The Movie Orgy, Hurwitz and Dante were turning something old into something new. They were also entertaining stoned audiences with funky head films whose plotlessness and free associative riffs and digressions appealed to the scrambled sensibilities of stoned late 1960s/early 1970s audiences.

The original footage in The Projectionist reflects the film’s fascinatingly bifurcated personality. Half of it has the gritty naturalism of cinema verite or the grubby character studies that were temporarily in vogue in Hollywood at the time, as studios embraced experimentation and social commentary in a way they never had before and perhaps never would again, and turned people like Peter Boyle into movie stars.

But even a groovy, progressive studio wouldn’t touch a movie like this, although a surprising number signed off on letting the film use footage of some of the biggest stars in film history, a veritable who’s who of Golden Age icons. Judging by the kind of low-budget and scruffy productions that were able to use footage of old movies back in the 1970s, all you seemingly had to do was get a studio archivist stoned and they’d thank you by letting you use as much of Citizen Kane as you’d like.

The other half of the original footage in The Projectionist has been shot and edited to look like alternately a silent adventure serial with McCann waddling into action as Captain Flash, dashing superhero and maker of many comical faces, or a French New Wave romance with McCann as a brooding young romantic opposite the lovely young Balin. Half the movie is so contemporary it hurts while the other half beckons fondly to a pre-Jazz Singer era of film and, in the French New Wave, a recent development it nevertheless depicts with the dreamy, faraway nostalgia of something that happened long ago.

A deep love and understanding of film permeates every frame, original and borrowed, but the film’s homage to silent comedy would have been benefitted from more in the way of actual comedy.

Hurwitz nails the visual language of silent films and the arthouse dramas of Truffaut, Godard and the like but the movie is sorely and strangely lacking in jokes. That consequently gives it the strange distinction of being a Rodney Dangerfield movie (after a fashion, he is unmistakably a supporting player here) that’s seemingly devoid of any punchlines, let alone that distinctive set-up/punchline delivery rhythm that would distinguish Dangerfield in the years and decades ahead as one of our most beloved shtick and joke-slingers.

The Projectionist may be short on traditional jokes but there’s nevertheless a trippy, Firesign Theater culture-jamming spirit that similarly carbon-dates the movie as a product of its tumultuous era. The movie is a shaggy, backwards-looking cousin to the experimental comedies Robert Downey Sr. was making on shoe-string budgets around the time, a scruffy oddity unencumbered by the dreary dictates of genre and convention and plot.

In keeping with its casually avant-garde bent, The Projectionist is full of meta-texual touches, like the marquee for the movie theater where McCann works listing The Projectionist itself as the movie showing, and McCann, Balin and Dangerfield as its stars. Through the magic of editing McCann attends the gala “premiere” of The Projectionist alongside folks like Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe and talks earnestly about, what else, his love of film and the essential escape he found in it as a young man.

Hurwitz, who also appears as an usher, obviously loved films. In the years ahead, he’d alternate between more movies about movies (the 1972 Charlie Chaplin documentary Chaplinesque, the clever 1989 mockumentary That’s Adequate, which lovingly mocks Roger Corman and his legacy of idealistic schlock) and soft core porn under the pseudonym “Harry Tampa.” Hey, everyone’s gotta pay the bills and he sure wasn’t going to do so with the royalties from a movie as tiny, if charming as The Projectionist.

An appealingly retro if terribly slight concoction, The Projectionist proceeds like a dream, but not, alas, a particularly memorable one.