1928's The Cameraman Features Buster Keaton at his Daredevil Best

As an actor, filmmaker and all-around superstar, Buster Keaton was a huge talent but a small man. Like contemporary and rival Charlie Chaplin, who was also five feet, five inches tall, that smallness had a symbolic as well as literal dimension. Keaton and Chaplin did not just play gentleman who were small of stature: they personified the Little Guy, the underdog, the scrappy, pushed-around nobody who cannot catch a break.

In their prime, these diminutive titans of silent comedy reigned as idealized everyman, pure-hearted dreamers innocently pursuing the girl and the American dream while beset at all sides by bullies, cops and other corrupt authority figures. They were Davids taking on Goliaths and triumphing because they were heroes as well as clowns, inspirational figures of pluck, resilience and all-American gumption as well as buffoons to laugh at.

In 1928’s The Cameraman, Buster Keaton’s protagonist, an aspiring newsreel photographer named Buster, is the smallest man onscreen at any given moment, often by a great margin. But it’s not just height that sets sad-faced little Buster apart from other men he’s competing with feverishly for the overlapping, intertwining prizes of his dream job as a dashing cameraman for MGM (who also produced and distributed the film, its first with Keaton, who would describe signing with the powerhouse studio as the worst mistake of his career) and his dream girl, Sally (Marceline Day), who works as an MGM secretary.

Buster isn’t just considerably shorter and smaller than his rivals; he also lacks their breezy self-confidence, bordering on cockiness. He’s the adorably scrawny runt of the litter scrambling madly to compete with Rottweilers and German Shepherds. Buster ekes out a modest living as a tintype photographer leading a Willy Loman-like existence selling his wares for ten cents a pop.

Then the would-be filmmaker falls head in love with Sally and sets out to be an achiever worthy of her, despite a near-total lack of talent combined with an equivalent dearth of common sense.

Buster trades in his trusty still camera for a more expensive, newfangled movie camera and sets about seeing what kind of danger he can get himself into. The Cameraman depicts newsreel cameramen as pioneers in the field of shameless, lurid tabloid entertainment. Buster and his peers (or rather the people he desperately wants to be his peers) are professional parasites, camera-toting vultures who swoop in where there is death and violence and misery and dismay and document the madness for the benefit of a rubbernecking public and their ghoulish bosses.

Buster is ambitious. He’s hungry but he’s also so green and incompetent that the first batch of footage that he shoots is so crazily over-exposed and double-exposed that it accidentally feels avant-garde, the unintentionally boundary-pushing work of someone unaware that rules even exists, let alone that he’s breaking them.

The picture of ragged formality in his neat little suits with ties, his face a tragicomic mask of perpetual low-level suffering, Buster is indefatigable in pursuing his goals no matter how impractical or impossible.

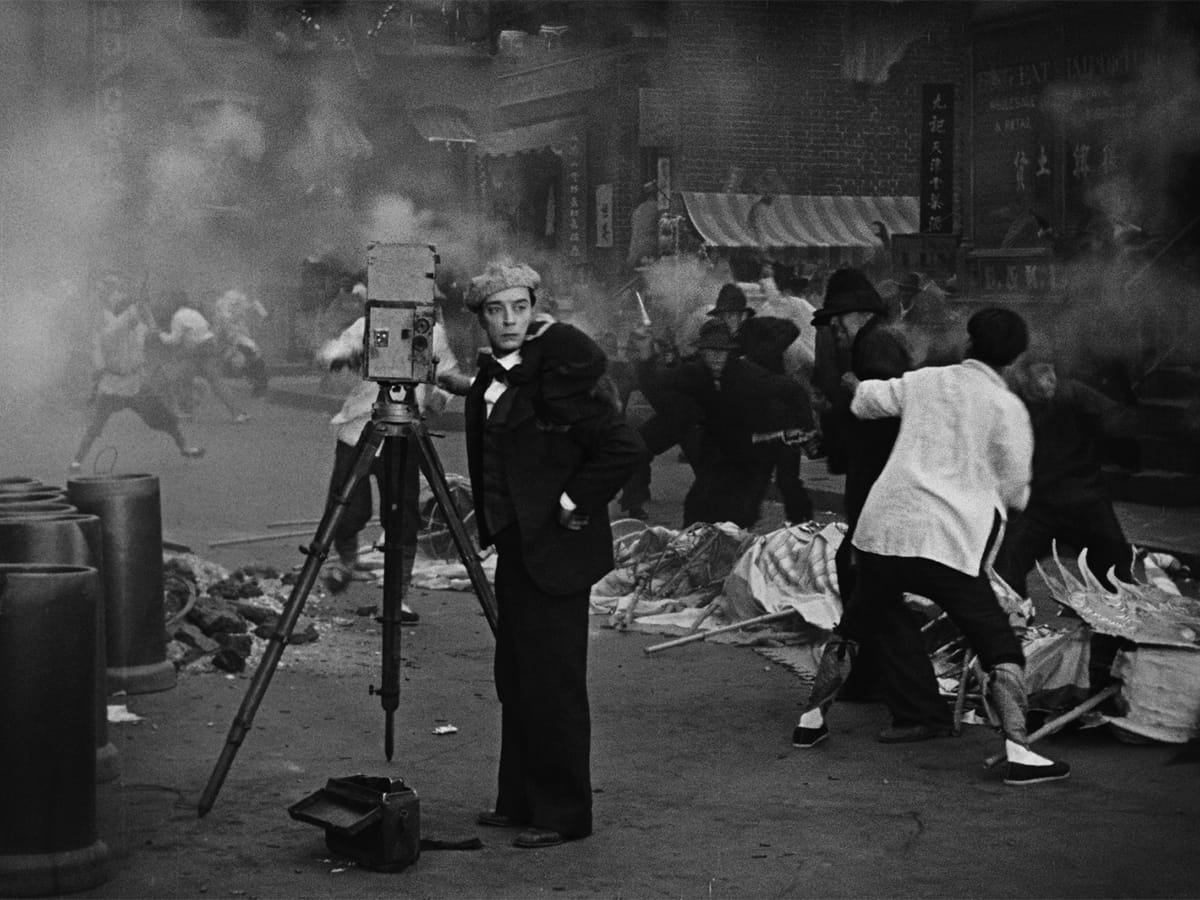

Buster is the hypnotic, unflappable calm in the eye of some violent storms, most notably a Chinatown celebration that devolves almost instantly into a vicious gang war between rival Tong gangs. Where saner, more reasonable souls would flee in terror out of concern for their safety and life, Buster just keeps on shooting, assisted, after a fashion, by a new primate sidekick.

The Tong War sequence illustrates what made Keaton, who, uncredited, co-directed the film with Edward Sedgwick, the credited director, such an incredible force as a filmmaker. It’s a spectacular, spectacularly funny comedy set-piece but it’s also a genuinely impressive piece of action filmmaking and even has elements of docudrama, since the gang war at the heart of the most impressive sequence actually happened, primarily in San Francisco, over a period of decades.

In its third act Buster has the good, if curious and zany fortune to pick up a simian sidekick who gets separated permanently from his organ grinder master/owner/partner in crime. This serves as another powerful illustration of one of the fundamental truths of comedy, silent or otherwise: everything can be made funnier through the addition of a funny little monkey, particularly a funny little monkey wearing human clothes.

Throughout all of the zaniness, all of the madcap action, all the intricately choreographed physical comedy Keaton maintains his trademark air of perfect deadpan, his legendary stone-face betraying nothing.

It takes the grace and dexterity of a world-class ballerina to so nimbly and convincingly portray a complete maroon the way Keaton does here. At multiple points in The Cameraman Keaton comes close to being naked for various gags and set-pieces and it becomes apparent that the comedy legend and counterculture icon was in almost suspiciously good shape physically.

Why wouldn’t he be? That’s another area where being short worked in his favor. In The Cameraman Keaton has the tight, sinewy, quietly muscular physique of someone who makes their living with their body, like a bantamweight boxer, a dancer or a gymnast. Keaton was an unexpectedly impressive physical specimen in his prime but the body that allowed him to do stunts and slapstick and shenanigans so effortlessly did not read onscreen as powerful. Instead it registers as something closer to the opposite: the tiny, inconsequential frame of a man who fundamentally does not matter, whom other, bigger, more confident men brush aside as someone who can’t possibly serve as competition or a threat.

MGM insisted that Keaton use stunt doubles for the first time to protect its new star/investment, but The Cameraman nevertheless benefits from the very real sense of danger that comes with real movie stars putting themselves in real peril for the sake of a gag.

Buster the wannabe cameraman will literally do anything to break into the film business, up to and including dying a horrible and easily avoidable death in the process. The actor and filmmaker playing him would similarly do anything for a laugh, even if it meant risking broken bones and the kinds of brutal injuries you never quite recover from, physically or mentally. The Busters share a sense of foolhardy fearlessness and total, pathological commitment; there’s a whole lot connecting them beyond a name and an industry.

Keaton was a daredevil as well as a craftsman, a stunt man as well as a stone-faced clown. Buster spends an awful lot of The Cameraman in harm’s way of various automobiles; he seemingly spends as much time riding vehicles from the outside as he does the inside.

That fearlessness is reflected in the character as well; he continuously puts himself in harm’s way, endangering his life in the process, because he simply doesn’t know any better. He’s a complete naïf who will not let anything get in the way of accomplishing his two big goals in the world but he’s also pure in that inimitable Buster Keaton way, an innocent spirit running amok in a corrupt world and business.

In many ways, The Cameraman marked the end of an era. It was not Keaton’s final silent film. That distinction belonged to its poorly received follow-up, Spite Marriage, which Keaton wanted to be a sound film, given its voluminous dialogue, but that MGM decided should be silent like all of Keaton’s biggest, most beloved and iconic hits.

In the years and decades to come the film business would change dramatically. Sound was of course the big game-changer. Being one of the kings of silent comedy, as Keaton undoubtedly was, rendered him a man instantly and permanently out of time and out of fashion, a relic of an earlier, more primitive era in film and comedy.

The Cameraman consequently represents the end of Keaton’s golden age and a particularly inspired stretch in his career that also produced such unassailable masterpieces of silent comedy as 1927’s The General and College and 1928’s Steamboat Bill, Jr.

The movies that follow would have an exciting, terrifying new element called sound but whether the film was silent or what was once known as a “talkie,” the goal for comedy lifers like Keaton and key collaborator Clyde Bruckman (who worked on the script for the film, as he did so many of Keaton’s classics) remained the same: make people laugh, and engage them emotionally in the process as well, something The Cameraman does extraordinarily well, with a deceptive ease that can only really be the product of hard work.

Check out my newest literary endeavor, The Joy of Trash: Flaming Garbage Fire Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free, signed "Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring book for free! Just 18.75, shipping and taxes included! Or, for just 25 dollars, you can get a hardcover “Joy of Positivity 2: The New Batch” edition signed (by Felipe and myself) and numbered (to 50) copy with a hand-written recommendation from me within its pages. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind collectible!

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Joy-Trash-Nathan-Definitive-Everything/dp/B09NR9NTB4/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= but why would you want to do that?

Pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

Check out my new Substack at https://nathanrabin.substack.com/

And we would love it if you would pledge to the site’s Patreon as well. https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace