Who Framed Roger Rabbit Will Always Be a Marvel and a Miracle

When Who Framed Roger Rabbit was released in 1988 it was rapturously received as a technological marvel, sure, but also as something approaching a miracle. Like similarly revolutionary but inferior films such as The Jazz Singer and The Birth of a Nation, it’s one of those milestones that single-handedly pushes an art form forward and expands the vocabulary and possibilities of film. Live-action characters and cartoons had co-existed onscreen before. Disney had experimented with combining live-action and animation in movies like Mary Poppins, Song of the South and Bedknobs and Broomsticks but never with the sophistication and flair exhibited here.

Combining animation and live action had always felt a little like a stunt before, a novelty, something that could be sustained for a set-piece or two but was too costly, complicated and difficult to sustain for an entire film. Who Framed Roger Rabbit made it feel real. It was the first live-action/animation hybrid to attain an unmistakable verisimilitude. If, as its tagline famously bragged, Superman made you feel like a man could fly, then Who Framed Roger Rabbit made you believe that cartoons and human beings could co-exist in the real world and the reel world.

It’s doubtful a production as insanely, almost prohibitively expensive, not to mention complicated and time and labor-intense as this could have been made without the enthusiastic backing of Executive Producer Steven Spielberg, at the time perhaps the single most successful filmmaker in Hollywood and, consequently, also a man people are very eager to please. It similarly did not hurt that Roger Rabbit reunited the Executive Producer with director Robert Zemeckis, whose similarly beloved Back to the Future he’d worked on a few years earlier.

Spielberg’s muscle helped make the impossible happen on a pretty regular clip in Roger Rabbit, whether that meant Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse sharing a screen together (to enjoy a chuckle at protagonist Eddie Valiant’s possible imminent violent demise) or the animated world’s two greatest duck entertainers, Daffy and Donald, realizing their destiny by playing a particularly violent and acrimonious round of dueling pianos.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit consequently represents a once in a life symbiosis of cultural and corporate interests, when Warner Bros. and Disney were willing to overlook their differences and rivalry and come together to help create the movie’s shadowy, impeccably lived-in cartoon universe.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit captured animation at a crossroads; the hand-drawn animation that gives the film much of its beauty and enduring power, the product of genius animators slaving away at their masochistic trade in pursuit, and realization, of perfection, was on its way out. Computer animation was the wave of the future. In this world of smooth, impersonal digital landscapes, animated characters would share the screen with human beings plenty, in the 2010 Yogi Bear movie, for example, but the frequently sorry results inevitably lacked the artistry, warmth and humanity of Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s animated, live-action and animated/live-action worlds.

Zemeckis, ever the restless pioneer of onscreen technology, would later attempt a fusion of animation and live acting with Polar Express, which is certainly a notable animation milestone, albeit of the nightmare-inducing variety.

In that respect, Who Framed Roger Rabbit represented the best of the old and the best of the new, a gorgeously realized 1940s setting that’s also a dizzily inventive meditation on the 1940s via state-of-the-art, never-to-be-surpassed live-action/animation rooted in the artisanal history of hand-drawn animation.

A spirit of free-floating anarchy defines the film even as every element has been designed and realized down to an almost molecular level. Every scene works on its own while further fleshing out the film’s singular universe and relentlessly pushing the film’s exquisitely conceived plot forward.

At the time of its release, Who Framed Roger Rabbit felt like an exhilarating new beginning, like the first in a series of films that would masterfully fuse the worlds of live action and cartoons. It turns out that the film represented such a dramatic evolutionary leap forward that nearly three and a half full decades later subsequent filmmakers never came close to matching Zemeckis’ instant classic in terms of combining live-action and animation, let alone topping it. Three decades on, Who Framed Roger Rabbit remains the gold standard. It seems safe to assume that it will never be topped.

In the years following the film’s zeitgeist-capturing success and ubiquity rumors swirled of a sequel, including a war-themed follow-up called The Toon Platoon, and lovingly animated, extremely expensive Roger Rabbit shorts, theatrically distributed like Disney and Warner Brothers shorts of yesteryear, kept these characters in the public circulation for a few years following Roger Rabbit’s release. But the long-threatened sequel never materialized, in no small part because of the incredible cost and work entailed, but also because the original would be impossible to match, both creatively and in terms of cultural impact. That’s probably for the best. A computer-animated Roger Rabbit movie would be no kind of Roger Rabbit movie at all to a lot of fans.

But it isn’t just Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s technological sophistication and beauty that has not been matched. We revere Who Framed Roger Rabbit because it is such a stunning, unmatched technological achievement, sure, but also because it represents just as audacious a creative achievement.

With Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Robert Zemeckis perfectly combined the worlds of Raymond Chandler and Tex Avery, creating the first ever Cartoon Noir, a world of shadows and darkness, shenanigans and pratfalls, femme fatales with gams that don’t quit and novelty moguls with hand buzzers and disappearing ink.

Forget The Two Jakes: Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a more satisfying spiritual sequel to Chinatown. Like Roman Polanski’s masterpiece, this posits a secret origin story for contemporary Los Angeles, a fiendishly believable riff on how a city of Angels and Devils got so exquisitely, hopelessly messed up and corrupt. Who Framed Roger Rabbit is one of the all time great neo-noirs and one of the all-time great cartoons but it’s also one of the great Los Angeles movies. It’s a movie as inveterately rooted in the oil-rich soil of Southern Los Angeles as American Graffiti or Los Angeles Plays Itself.

The wonderful Bob Hoskins, in a performance all the more effective and funny for the actor playing everything more or less completely straight, trades his Cockney accent for an American one as Eddie Valiant, a troubled gumshoe who has drowned his troubles in hooch ever since his brother and partner was offed by an evil toon. Eddie’s days are a dreary blur of dirty jobs done solely for the loot until he becomes mixed-up in the complicated romantic and professional life of Roger Rabbit (voiced by Charless Fleicher), a slapstick cartoon superstar who has been missing pratfalls because he’s afraid his sex-bomb lounge singer wife Jessica (Kathleen Turner, with an incendiary sensuality that makes her performance in Body Heat seem positively schoolmarmish by comparison) is stepping out on him with another man.

In the grand tradition of hardboiled fiction, this is an infidelity case that turns out to be about a whole lot more, namely a massive, sinister conspiracy involving Toontown, the surreal ghetto where toons live, and the future of Los Angeles public transportation.

It would be inaccurate to describe Who Framed Roger Rabbit as a movie that prioritizes intricate plotting or characterization over gags. For cartoon characters, gags are characterization. Gags are life. Toontown is a world of cartoons so it is by definition a world made up of gags. Who Framed Roger Rabbit represents a masterful exercise in world-building, and the world it builds is made up of gags, of jokes, of laughs.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit opens with an elaborate fake out in the form of a gorgeously animated short film in the vein of Merrie Melodies or early Disney cartoons in which disaster-prone baby Huey just barely averts death thanks to his overwhelmed baby-sitter Roger.

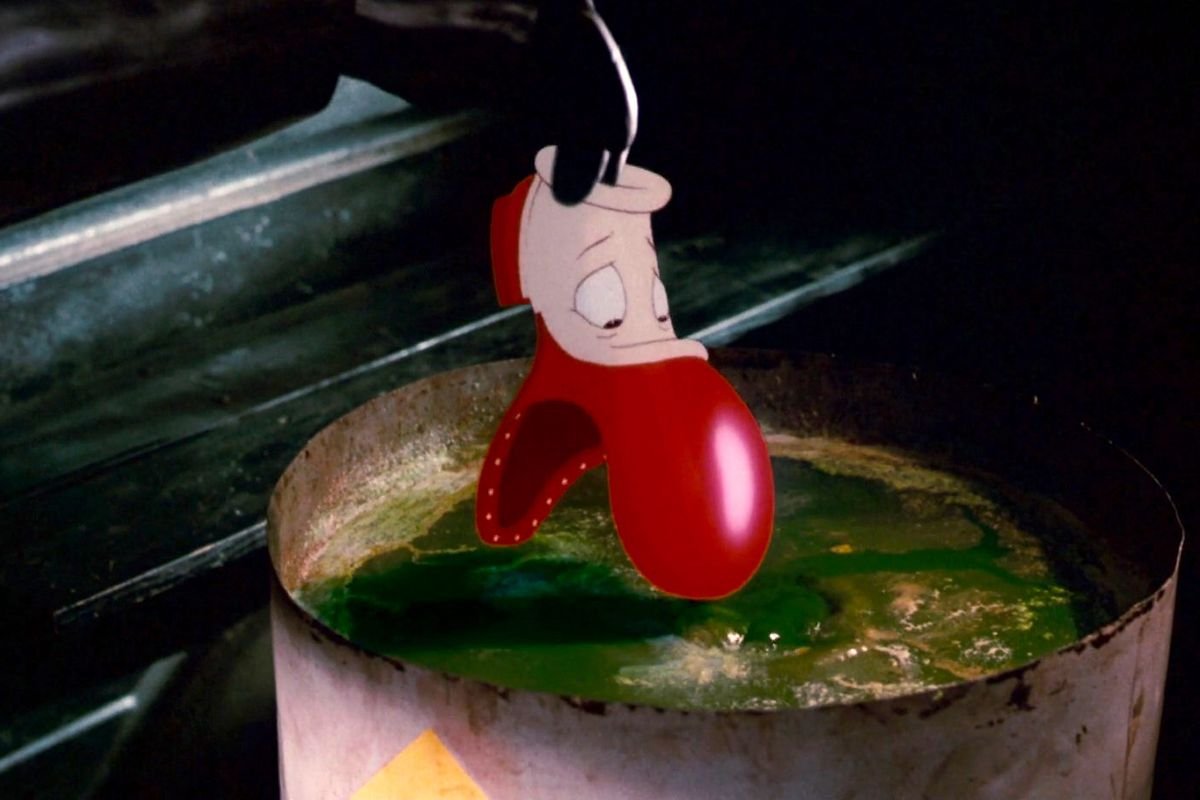

Even at its most kid-friendly and cartoonish, Roger Rabbit inhabits a universe where violence and death lurk around every corner. Rabbit explores to both comic and tragic effect the considerable overlap between nihilistic cartoon slapstick and the very real violence of hardboiled fiction and Film Noir.

Given the character’s extraordinary popularity, perhaps it’s not surprising that Jessica Rabbit might just be the element of the film that has been ripped off the most extensively. It’s similarly unsurprising that she’s also the element that has been ripped off the least successfully. Countless animated and animation/live-action hybrids that followed in the wake of Roger Rabbit’s success tried to replicate the character’s heat, glamour and sensuality and only ended up with characters that are inappropriately sexual, like Space Jam’s Lola Bunny.

The genius of Jessica Rabbit is that she’s appropriately sexual. She’s designed to be a roaring hurricane of ripe sensuality. The movie needs her to be so overwhelmingly sexy and desirable that her mere presence transforms grown men, toon and human alike, into stuttering, stammering, overwhelmed children. In hindsight, it’s amazing the movie slid by with a PG when Jessica’s curves and essence alone would seem to push things deep into PG-13, if not R territory.

It seems weird to say this, since his name is in the title, but Roger Rabbit might be the film’s most underrated character. It’s certainly tough to compete with a force of nature like Jessica Rabbit (the sexiest ever woman in a movie other than Maggie Cheung in In the Mood for Love) and a preeminent bogeyman like Judge Doom (Christopher Lloyd truly had a powerful link to the imaginations of kids in the 1980s) but as voiced by journeyman comedian and voiceover artist Charles Fleisher in his greatest role, Roger is a surprisingly three-dimensional character, a sweetheart of a guy with a big heart and a poignantly irrepressible need to entertain and please no matter the circumstances. The not-so-smutty joke at the film’s heart is that Roger and Jessica’s marriage is a real and healthy one and Fleischer’s performance makes it strangely palatable that a woman who looks like her could genuinely love such a genial idiot.

On a similar note, pretenders to Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s throne have aspired to be as bracingly dark and adult as the Disney blockbuster and only succeeded in being astonishingly inappropriate for children.

Roger Rabbit is dark alright, but it’s appropriately dark. It’s deliberately, purposefully, meticulously adult in its sensuality but also in its pitch-black humor, its violence and its overarching cynicism regarding human, and toon nature. For a Touchstone production, it’s remarkable how much bracingly adult content slipped in. This is a movie with an alcoholic protagonist who drinks constantly, terrifying weasel henchmen toting around all-too-real guns, one of the sexiest characters in the history of film, a Toontown that’s more like a bad peyote trip than a sunny nostalgic reverie and, in Judge Doom, a character who isn’t just scary: he’s nightmare-inducingly disturbing. This is a PG movie with an R-rated soul, a high-class Touchstone smash encouragingly and surprisingly in touch with its inner Ralph Bakshi, an instant smash that manages to sneak a whole lot of adult darkness and perversion into the margins.

Roger Rabbit has enough respect for audiences to understand that sometimes the best thing you can do to a family audience is traumatize them in an incongruously healthy way. Roger Rabbit made a fortune playing to the broadest possible audiences without taming the exquisite naughtiness at its core. It’s a waking nightmare, a feature-length sex joke rich in lusty double entendres and an appropriately apocalyptic explanation for Los Angeles car culture in the 1940s that just happened to be a movie families loved, one that would prove impossible to follow up, for an entire industry and art form, not just for a prodigiously talented set of filmmakers and craftsman working at the apex of their extraordinary ability.

Would you like to read a MASSIVE book about movies like Who Framed Roger Rabbit?! Then check out the Kickstarter for The Happy Place’s next book, The Fractured Mirror: Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place’s Definitive Guide to American Movies About the Film Industry here: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/weirdaccordiontoal/the-fractured-mirror?ref=project_build

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al, Felipe Sobreiro and my “Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring. book when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store! That’s a 10.50 value for free!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!