Barton Fink Is a Mesmerizing Nightmare of Hollywood Emptiness and Capitalist Depravity

Barton Fink semi-famously began life as the script Joel and Ethan Coen wrote while struggling to finish the screenplay for Miller’s Crossing. It’s a product of writer’s block that perhaps not coincidentally is about a ferocious case of writer’s block experienced by a painfully earnest, agonizingly sincere playwright based on Clifford Odets after he follows the money trail from dynamic, gritty, real New York to the sunny den of spiritual corruption and soiled innocence that is Hollywood, USA.

So Barton Fink’s strange legacy is tethered forever to the more ambitious film the Coens were writing when they decided to take a break and work on this weird, small little story about the gothic comeuppance of a self-styled poet of the common man. But the film is also linked inextricably to another Coen Brothers movie, Hail Caesar.

Barton Fink and Hail Caesar function beautifully as companion films defined as much by their differences as their similarities. Barton Fink is an inveterately Jewish film about Jewish studio executives and Jewish leftist activism and the rich, complicated history of Jewish writers being used and abused by Hollywood. Hail Caesar, in sharp contrast, is as Christian as the Coen Brothers get.

Barton Fink and Hail Caesar riff extensively on real-life show-business figures but Barton Fink centers on a man of ferocious inaction, a scribe who has temporarily lost contact with his muse, while Hail Caesar is about a man of action, a fixer whose existential purpose in life is to get things done.

Hail Caesar is about the ultimate insider while Barton Fink is about an outsider in a strange land, a man whose fierce if hypocritical code of ethics means nothing to the sausage-fingered vulgarians he works with. But before Barton Fink (John Turturro) fails spectacularly in Los Angeles, he triumphs in New York.

The Coens’ black comedy opens with Fink in a moment of neurotic triumph as critics and audiences swoon over his latest hymn to the fishmongers and laborers of the world. Odets is an irresistible satirical target for the Coens because he took himself incredibly seriously. He was earnestness personified. The purple poetry of his achingly sincere melodramas today radiate clunky self-parody rather than righteous rage. And though Barton Fink presents the Hollywood excursion of an Odets-like writer as a regrettable mistake, the best work Odets ever did was for the big-screen, specifically co-writing the screenplay for Sweet Smell Of Success.

Odets’ propaganda for the proletariat is otherwise hilariously dated. It represents less the actual lived experiences of the American working man than a ridiculously idealized progressive/Socialist fantasy of working-class nobility. The point the Coens drive home over and over again is that pretentious blowhards like Odets and Fink adore the working class in abstract, as a concept, as an amorphous entity to champion and defend, but are freaked out to actually encounter poor or struggling people in real life. In theory, their work represents an ongoing cultural conversation about class and revolution and solidarity. In actuality, they’re less interested in learning from their ostensible subjects than in talking down to them. They don’t want a conversation, they want to monologue.

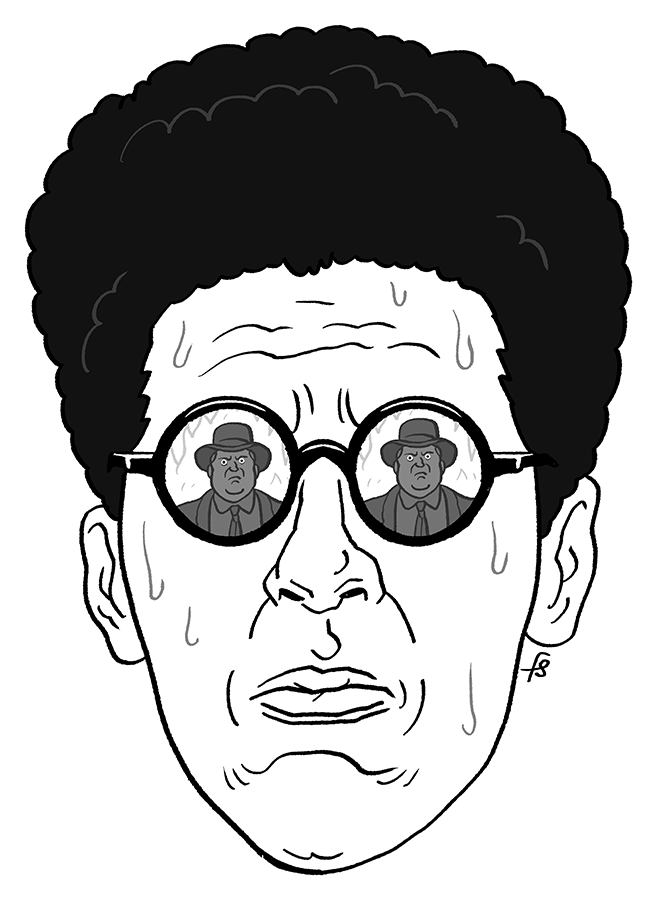

After making the trek to Los Angeles, Fink finds himself in the curious position of being asked to write a Wallace Beery wrestling picture by Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), a corpulent, motor-mouth mogul who elevates real-life MGM head Louis B. Mayer’s notorious penchant for personal histrionics and melodrama to hilarious extremes. Lipnick is even more intent on avoiding conversation than his overwhelmed new employee but he delivers his crackling banter at such a machine-gun clip and with so many asides that it almost sounds like he’s having an intense argument with himself.

Lerner acts as if talking is an Olympic event and he’s intent on winning the Gold Medal for speed and ferocity. Lerner’s performance is essentially one giant solo. He was nominated for an Oscar for best supporting actor for the role, and as is generally the case, he got the nod for both the quality and quantity of his acting.

Lerner embodies the sycophantic false promise of show-business. In lines that have been widely recycled in cult film and writing circles, Lipnick tells Fink, “The important thing is we all have that Barton Fink feeling, but since you’re Barton Fink, I’m assuming you have it in spades.”

Fink comes to learn just how little the “Barton Fink feeling” means when he holes himself up in a decaying slab of hell called Hotel Earle. Hotel Earle is no ordinary hotel. It has a tortured and twisted soul of its own. It sweats in the pounding, unrelenting heat. Sweltering weather causes the wallpaper to peel off the wall.

The hell hole where the vast majority of Barton Fink takes place suggests the Coen Brothers’ version of The Shining’s Overlook Hotel. They’re both bad places where bad things happen to bad people, animistic architectural beasts filled with the very worst vibes. They’re less places to stay than prisons to flee.

At various points, Hotel Earle suggests both a purgatory that our clueless protagonist has been banished to for some unknown sin, and hell itself. Cinematographer Roger Deakins emphasizes the sanity-shredding heat of Los Angeles, the way it grinds people down. The film’s characters are marinating in their own juices, particularly Charlie (John Goodman), an insurance salesman with a friendly smile and a jovial personality who offers his hotel neighbor booze and friendly conversation.

In Hollywood, people talk at Barton but Charlie is genuinely interested in forming a real human connection with Barton despite their obvious differences. Finally, Barton has a real working man to talk to and learn from, and a man overflowing with stories he’s eager to share with Fink. Yet in one of the film’s central tragedies, Barton is patently uninterested in anything Charlie has to say. He’s intrigued by him as a symbol of the working class but he’s not only unwilling to actually listen to Charlie, he seems incapable of listening as well. He’s more interested in explaining his take on the plight of the common man than in letting this seemingly humble and unassuming man talk about his own plight.

Barton is damned by his own arrogance, narcissism and overbearing pretension. In Hollywood he’s utterly lost. He cannot understand or comprehend the weird power dynamics between Lipnick and the people who work for him. He reaches out to a legendary Southern novelist based on William Faulkner and played by John Mahoney for direction in this strange new world, and only discovers that this great man, this icon of the written word, is even more lost than he is, and relies on a “secretary” played by Judy Davis not just for emotional support, but to do much of his actual writing for him.

Fink initially seems to see his Hollywood jaunt as a means to an end. He views it as a short, lucrative way to finance his leftist-theater-writing compulsion, but the longer Fink stays in L.A, the more it comes to feel like something he can’t, and won’t be able to escape. It’s his Hotel California, and he can check in whenever he wants, but it’s not clear that he’ll ever get to leave, or whether this monstrous city and this monstrous industry will swallow him whole.

Once the bodies begin to pile up, Barton Fink shifts from being an inside-baseball dark comedy about a road to hell paved with Socialist good intentions and becomes equal parts psychodrama and gothic horror film. The friendliest, most affable person in the movie (Charlie) turns out to be not just a little off but a raging sociopath, a serial killer who punishes his friend Barton for his hypocrisy and self-absorption by transforming their shared dwelling from a hell hole to a literal hellscape.

That agonizing, ambition-killing Southern California heat morphs into the very flames of hell as Charlie, his mask of sanity and good-natured affability finally removed, burns down Hotel Earle as his magnum opus of insane destruction. Barton gets close enough to one very strange working man to nearly be destroyed by the encounter.

Like Hail Caesar, Barton Fink is minor Coen Brothers. But its bleak, gothic charm is wrapped up in its relative modesty, in the way it reduces the rollicking, maddening carnival of show-business to the tortured interior of an outsider who just barely survives Hollywood. It may have began life as an escape from Miller’s Crossing but its legacy is just as substantial as the brothers’ characteristically brilliant foray into mob movies.

We still all have that Barton Fink feeling but Barton Fink has got it in spades. It has the curious quality of being at once highly specific and oddly relatable. Not everyone tangles with serial killers, famous writers or Wallace Beery but Fink’s disillusionment at the hands of a business he’s right not to trust is surprisingly universal.

In Barton Fink, Hollywood is less a dream factory than a waking nightmare. It’s about a man and a hotel that are both ineffably haunted, and its most resonant horrors are of the psychological variety.

Want an entire book full of pieces like this? Then check out the Kickstarter for The Happy Place’s next book, The Fractured Mirror: Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place’s Definitive Guide to American Movies About the Film Industry here: https://tinyurl.com/2p8dn936

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!