There Will Be No Blues Brothers Convention This Year, Tragically, But I'll Always Have My Golden Memories of Last Year's Celebration

When I was researching You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me, my 2013 book about my deep immersion in the surprisingly simpatico fandoms of Phish and Insane Clown Posse I fell in love with the spooky, gothic Midwest.

I grew besotted with nowhere towns full of struggling, soulful people, with industrial hellholes where hope left ages ago along with anything resembling good jobs.

These are the places I rocketed through on buses and trains and planes, chasing a band, a festival, a feeling and ultimately redemption. These curious burghs are where I found salvation, personally and professionally.

My love of the gothic midwest is a big part of the reason I go to counter-intuitive extremes to ensure that I am at the Gathering of the Juggalos, Insane Clown Posse’s annual festival of arts and culture, year after year.

I love the world ICP has created in its music, but I’m also fascinated by Cave-In-Rock, Illinois and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and Thornburg, Ohio and all the other weird places Juggalos have gathered.

I’m awful nostalgic for the Gathering of the Juggalos but this year the Gathering-shaped and sized hole in my soul was filled by the first ever Blues Brothers Convention in Old Joliet Prison in Joliet, Illinois.

It’s not the Gathering but it fulfills many of the same emotional and professional needs, chief among them a desire to once again leave my comfortable womb in the South and plunge deep into the heart of my beloved Midwestern gothic.

A two day celebration of a silly Saturday Night Live comedy in a haunted realm where generations of doomed men fought and fucked and died and suffered unimaginable torments sounded gothic as hell.

He’s not Shaggy 2 Dope or Violent J but Old Joliet Prison has wicked clowns of its own.

I’ve seen Insane Clown Posse play such spooky locales as a haunted house designed by Rob Zombie (you know he’s spooky because his last name is Zombie!) and a strip mall in Canada and no place I’ve ever seen the Wicked Clowns perform has been a fraction as unnerving as Old Joliet Prison.

I felt like I was in a heavy-handed horror anthology, possibly one directed by Rusty Cundieff, and the spirits of all the men who died unmourned deaths in this pit of suffering would rise up and attack us for partying in their forever homes.

It was not unlike a ghost tour I took with my wife and her family in Savannah, Georgia. For some reason, I thought it would be fun but it didn’t take long to figure out that all the ghosts were angry because they were slaves who were murdered and vivisected and then set on fire.

Being reminded constantly of our nation’s shameful racial history took all the fun out of the Savannah Ghost Tour. The real, enduring horror has nothing to do with ghosts or ghouls or things that go bump in the night. It’s capitalism. It’s always capitalism!

That’s certainly true of the Old Joliet Prison. It’s a sad realm of broken lives and lost souls where you can feel the dark, violent energy deep in your bones. The overwhelming aura of misery, suffering and despair sometimes makes it hard to enjoy the singing of James Belushi.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

In true Midwestern gothic form, Old Joliet Prison is beautiful in its ugliness.

It’s a towering monster of brick and steel and wire, broken and falling apart, a grotesque caricature of its former self.

It is, in other words, a weird fucking place to throw a party and the Blues Brothers Convention’s setting in a former prison was simultaneously amoral and borderline unforgivable and the most fascinating and memorable element of the whole cursed, blessed weekend.

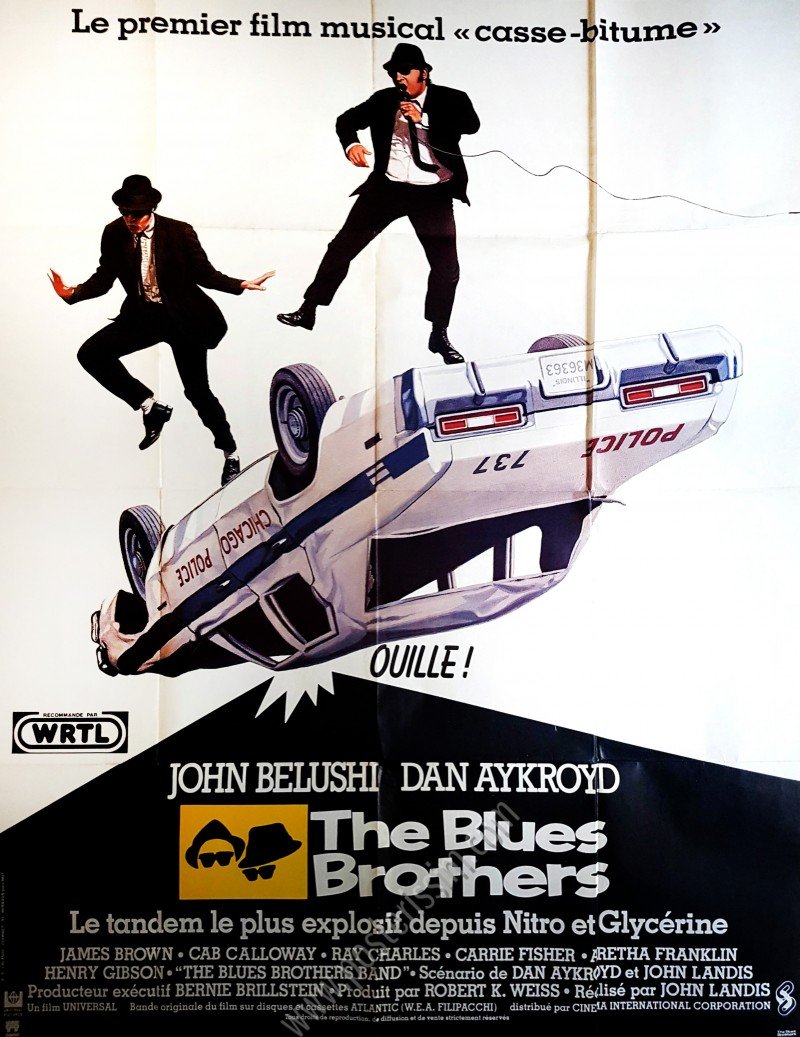

Within the context of The Blues Brothers, Joliet Correctional Center is the hellhole out of which Joliet Jake (John Belushi) emerges after three years in the big house.

The film’s opening shot depicts industrial Illinois as a circle of hell, a smokestack and pollution-choked wasteland. One of the things that I love about The Blues Brothers and if this weekend did anything, it reaffirmed that I do, indeed love the motion picture The Blues Brothers is how fucking dirty it is.

In his god-like late 1970s/early 1980s prime, when he gave the world Kentucky Fried Movie, Animal House, The Blues Brothers, An American Werewolf in London and Trading Places before, you know, all that unpleasantness happened, John Landis gave The Blues Brothers a pervasive sense of grit and grime.

The Blues Brothers is cinematic in a way subsequent Saturday Night Live movies never aspired to be. Landis set out to make the It’s a… Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World of the early 1980s, a wonderfully wasteful exercise in cinematic slapstick that achieves the dream of countless five year olds in smashing up over one hundred cars pretty much for the thrill of it.

In the 1970s and 1980s a magical substance known as “cocaine” allowed filmmakers to make movies on a scale previously never imagined possible, at least by people who were not coked out of their gourd 24-7.

Because of all the drugs, and the waste, and the insanity, The Blues Brothers’ budget swelled from seventeen and a half million dollars to thirty million dollars. That massive budget was necessary in order to blow up all of that stuff as well as possible.

When newcomers do not know the limits or what they cannot do, they sometimes accomplish the impossible the first time around, and are cursed to chase that naive masterpiece the rest of their careers.

That’s Aykroyd as a screenwriter here. He apparently wrote a three hundred and twenty-four page original draft designed to be a two-part film. It was not unlike his original draft for Ghostbusters, which was similarly prohibitively long and prohibitively expensive.

In both cases Aykroyd’s scripts were re-worked into something more palatable by a more pragmatic collaborator. With The Blues Brothers, that was director John Landis. With Ghostbusters, it was co-star Harold Ramis.

As a child I understood intuitively that by wasting as much of Universal’s money as possible by blowing up buildings and crashing cars the filmmakers were doing God’s work and creating a legacy that would live forever.

I was right! In 2020, the fancy folks over at The National Film Registry deemed the Saturday Night Live spin-off “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” and on August 19th I attended the very first Blues Brothers Convention inside the aforementioned Joliet Prison.

I know that The Blues Brothers is culturally, historically and aesthetically significant in my own life. I grew up seeing The Blues Brothers as the unofficial official movie of Chicago.

Growing up in Chicago, everybody had seen The Blues Brothers, generally more than once. It didn’t matter that it was rated R for profanity and violence. It didn’t have boobs or anything, so obviously it was acceptable for everyone.

The guy who ran the group home where I grew up before he was given the boot for smoking the sweet leaf used to turn his smirk in my direction, wink at me and say, “We’re on a mission from God” whenever we had to pretty much anything.

It was corny and moderately annoying yet endearing at the same time. That he never had to tell anyone where the reference was from speaks to how deeply pretty much every element of The Blues Brothers is woven into the fabric of American but particularly Chicago life.

As a young critic I rebelled needlessly against the cult of The Blues Brothers as well as associated fare like Ghostbusters and Caddyshack. I thought it was part of my sacred duty as a snob to turn up my nose at these lowbrow romps populated by TV-trained vulgarians.

Then I got the fuck over myself and realized that the reason my generation has an intense relationship with these movies is because of nostalgia and childhood and seeing them for the first time in a pre-critical state.

I’m not exactly sure when, but sometime deep in adulthood my father developed an interest in the blues. I didn’t exactly know why at the time but I do now. My dad dug, and continues to dig, the blues because my dad has experienced the blues.

He’s known divorce and heartbreak and unemployment and disease and the vulnerability, despair and dread that comes with being a disabled, unemployed single dad with no idea how he’s going to get by.

When he was still able to leave his nursing home, when I visited my dad we’d go to Rosa’s Lounge in Chicago and see whoever happened to be playing that evening. My dad just wanted to hear someone sing about sadness and confusion. He wanted the consolation of knowing that pain and suffering are universal, that we’re all united in feeling the blues.

That was a bond we shared and continue to share: blues music and clinical Depression. It’s the family curse, my unfortunate birthright and something that I am terrified I have passed down to my two sons.

Chicago was another bond we have shared. I was a third generation Chicagoan but I got the hell out in 2015 after getting laid off by The Dissolve and sold my condo on the north side at a massive loss. I bought my condo for 185,000 dollars and sold it for 153,000 dollars just a few years later. Factor in twenty grand in unexpected random fees and I lost every penny I put into that place and more.

That couldn’t help but have a profound effect on how I see Chicago. I loved it with my whole goddamn soul. It never stopped breaking my heart. Being Nathan from Chicago and Nathan from The Onion were so central to my identity and my self-esteem in my twenties and thirties that I had to figure out who I was when I lived in Georgia and no longer wrote for my old employer.

So my feelings about The Blues Brothers are intensely personal, emotional and wrapped up in nostalgia, family and my love-hate relationship with Chicago.

But the soul deep affection I feel towards The Blues Brothers is also rooted in its grubby glory, its cockeyed, coked-up majesty.

For the first and last time, a Saturday Night Live movie somehow had all the resources in the world, including a shockingly justified ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY TWO MINUTE RUNTIME.

Why did it need well over two hours to tell the story of two deadpan musical dudes trying to raise money to save the orphanage where they grew up? For starters, it takes time as well as money to blow shit up and crash cars and few films have been as ferociously devoted to blowing shit up and crashing cars as The Blues Brothers. It feels like it was made by the world’s most talented and least disciplined twelve year olds in the best possible way.

Then again, Aykroyd was only twenty-eight when he co-wrote and starred in The Blues Brothers so he was still a kid in many ways. He was a Canadian by birth, regrettably, but a Chicagoan in spirit. A Canadian does not write and star in the ultimate Chicago movie by accident.

Aykroyd created such a profound legacy as a young man that forty-two years after The Blues Brothers’ release he could return to Joliet, where its opening scenes take place, a conquering hero alongside James Belushi, nobody’s idea of an acceptable substitute for John.

Because of the unusual way my brain works, I have spent way too much time thinking about the curious existential plight of James Belushi. I can’t imagine what it would be like to grow up in the vast, intimidating shadow of an older brother who was arguably the most explosively talented comic performer of his generation.

What Brando was to drama Belushi was to comedy. He embodied the form. He was pure. He was intuitive. He was a genius. For seven glorious years he blazed brightly before burning out.

Instead of pursuing a different path in order to escape his brother’s shadow, James chose to do EVERYTHING that his brother did. He did Second City and then Saturday Night Live, just like his brother, before becoming a movie star.

And, somewhere along the line, James Belushi joined Dan Aykroyd in what passes for the Blues Brothers these days.

Going the Second City-Saturday Night Live-Blues Brothers route didn’t just invite comparisons between the preeminent comic martyr of his generation and his hopelessly inferior younger relation: it demanded them.

Those comparisons couldn’t help but make Jim seem hopelessly inadequate by comparison. Indeed, the best that could be said of James Belushi’s performance Friday night at the Con alongside “The Blues Brothers” is that it was good enough, and I don’t think it merited even such mild praise.

James has led a charmed life of wealth and fame and opportunity but it came at the cost of existing forever in his dead brother’s outsized shadow, of knowing that people would look at him and always see someone who was just like John Belushi but much less talented, charismatic and likable.

Why do I look like a cut-out here?

If James is doomed to a cushy if existentially uncomfortable existence as the ersatz Belushi/Blues brother, Aykroyd is the real thing. But he’s the real thing over four decades later, so it’s a softer, squishier, less hungry and more complacent version of the virtuoso who dominated mid to late 1970s television and early to mid 1980s film.

The primary visual motifs of The Blues Brothers Convention were Dan Aykroyd alongside a Belushi of wildly variable quality and human suffering. Everywhere you looked you were reminded of the classic 1980 comedy and all of its quotable lines, iconic scenes and unforgettable characters, or the broken, sadistic and ultimately unsustainable nature of our prison system and how its woeful inadequacies reflect and mirror the savage iniquities of late-period capitalism.

The Joliet Prison, which was turned into a museum in 2018 after being shut down as a prison in 2002 partially due to what Wikipedia refers to as the “obsolete and dangerous nature of the buildings”, several of which burned down, was transformed into a gloomy theme park version of Chicago. There were DJs and art instillations and a food court styled after Chicago’s old Maxwell street fair and a stage for local acts where the sound was consistently drowned out by the bands playing the main stage.

The Kid!

Most excitingly, there were an assortment of famous cars to take pictures with. One of these automobiles, gloriously enough, was the Blues Brothers 2000 Mobile.

That’s just like the regular Blues Brothers Mobile but a massive failure that everybody hates.

I was psyched! As someone perversely fascinated by Blues Brothers 2000 I wondered if there would be ANY acknowledgment whatsoever that eighteen years after The Blues Brothers became the 10th top-grossing film of 1980 a late-in-the-game sequel was released that pursued a quantity over quality approach to replacing the utterly irreplaceable John Belushi by introducing John Goodman, some child actor and the great Joe Morton as replacement Blues Brothers so woefully lacking they make James Belushi seem like a satisfying replacement by comparison.

Ah, but it was not the ACTUAL car used in the flop. It was instead a replica commissioned by a private collector who is also apparently the world’s biggest/only Blues Brothers 2000 super-fan.

The real Blues Brothers 2000 mobile is, of course, in the Smithsonian. Or so I imagine.

Blues Brothers 2000 is represented by a cut out of Aykroyd in costume and a cut out of J. Evan Bonifant, AKA the Kid. John Goodman and Joe Morton were nowhere to be seen. It was almost as if they realized that the sequel was an embarrassment and are appropriately ashamed.

The cars included the iconic automobiles of The Blues Brothers as well as the Ghostbusters car. It was decidedly off-brand but as a Gen-Xer I was not about to complain about excessive access to one of the most iconic vehicles of my childhood.

My inner child was deliriously happy, in part because I had fed it the kind of adult drugs that allow you to stay up late and genuinely enjoy listening to James Belushi perform music.

But nothing made as big of an impression on me as the jail. It didn’t just have bad vibes or an unfortunate past: it was fucking evil. Listen closely and you could hear the ghostly howls of long-dead inmates as they unsuccessfully fended off sexual assaults or bled out after getting shanked in the prison yard.

The Old Joliet Prison houses a Haunted House during the Halloween season. That seems appropriate, in that the former prison already feels like a horror movie set, and in terrible taste, since it’s ghoulishly trading on Joliet Prison’s real life history as a place where violent, hopeless men suffered and died. And those were just the wardens and guards! The prisoners had it worse .

Who you gonna call?

The museum’s displays do not sugarcoat its past. They make it clear that the prison was designed as a bad place to punish terrible people. I couldn’t begin to imagine the torment of actually living in a place like this.

The Old Joliet Prison is consequently a strange place to open a raucous musical comedy but it also establishes Joliet Jake as a man who knows the blues intimately.

Even when he’s released, Joliet Jake is still an ex-convict. In our society, that’s only a step up from being a convict. You’re free but held in perpetual suspicion.

Surveying the disproportionately mustachioed, aggressively Midwestern crowd at the Blues Brothers Convention I couldn’t help but notice that this celebration of black music and black culture was almost entirely devoid of black people.

David Duke rallies are more diverse. It boggles the mind, but it is entirely possible that people of color are somehow averse to paying money to hear James Belushi perform black music.

At any given time, there seemed to be more black people on the main stage than in the audience. This only added to the perception that The Blues Brothers is a love letter to black music with a following that is blindingly white.

Aykroyd set out to make music that would lead listeners to his heroes. Instead comedy fans bought the band’s multi-platinum breakthrough album Briefcase Full of Blues and dug it enough that they figured that it was the only blues album they would ever need to own.

To their credit, Aykroyd, Belushi and Landis very aggressively shone a light on a who’s who of all-time great soul legends like James Brown, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and Cab Calloway at a time when the studio was aggressively pushing the likes of Donna Summer and Rick James.

The Blues Brothers’ albums and movie were supposed to serve as a gateway to a wonderful world of black music but plenty of white folks seemed to have stopped permanently at Belushi and Aykroyd.

The Blues Brothers are essentially a cover band. The essence of a cover band is that if you like the covers then you will LOVE the originals but Blues Brothers fans frustratingly seem to feel that the covers will do just fine.

The groups that opened for “The Blues Brothers” perform the style of contemporary blues where a singer will complain about a woman for a verse and then there are fifteen minute guitar and organ solos. That’s a style of music than generally leaves me cold unless I am on a lot of drugs. In that case I feel like I have a weird spiritual connection to the electric guitar.

The performer who played just before the night’s closing act was Carlos Delgado. He’s legendary in Blues Brothers circles as the man who got Belushi into blues music when Belushi was shooting Animal House in Oregon.

It’s crazy to think that a pair of hipster comedians got a hard on for the blues in the late 1970s and that changed the trajectory of their lives and careers, and the blues itself, for posterity.

At the Blues Brothers Con we were experiencing that weirdly massive legacy in its purest form.

It was a family affair, so after Carlos Delgado, the man who infected John Belushi with a life-altering passion for the blues, performed there was a surprise performer in the late, beloved Saturday Night Live legend’s wife, Judith Jacklin Belushi Pisano.

Back in Wheaton, Illinois, where it all began, John Belushi and his future wife were small town high school sweethearts. They were a study in contrasts. He was famously a seemingly indestructible wrecking ball of a man, a fire hydrant-shaped dynamo with enough energy to power several small countries. The love of John Belushi’s life was a small, waif-like spirit with a lilting bird voice.

She began her surprise set by announcing that she had laryngitis but was going to try to sing anyway.

As the responsible, sensitive keeper of John Belushi’s legacy, she had all the goodwill in the world but this was a crowd that was eager to hear aging funnymen perform sloppy party music so she was at a distinct disadvantage.

She persisted all the same, with the considerable assistance of back-up singers who clearly had better, stronger voices than the Samurai Widow even when she did not have laryngitis. But none had her simultaneously tragic and triumphant history as the soul mate of one of the greatest American entertainers.

Her performance was politely received before the main event: what my ticket for the convention referred to as Dan Aykroyd and James Belushi as “The Blues Brothers.”

Fun!

I’m not sure whether it was designed as such, but this billing clearly acknowledged that what we had paid a modest sum of money to see was not, in fact The Blues Brothers but rather a passable simulacrum featuring a younger brother whose sad existential destiny is to never be good enough, no matter how hard he tries.

And oh sweet lord does he ever try! As Joliet Jake Blues, one of the REAL Blues Brothers, John Belushi was a passionate, enthusiastic amateur who made up for in energy, charisma and personality what he lacked in polish, experience and technical skill.

James Belushi likewise goes all in on energy and enthusiasm but that’s all he’s got. He doesn’t have the charisma and personality that made his brother so beloved but he is almost suspiciously peppy.

As the headliner Saturday night, James Belushi gave it his all, God bless him. He did crowd work. He rubbed his big middle-aged belly in a way that was disturbingly sensual. He talked lasciviously about the ladies, and invited a number on stage to dance very whitely.

James Belushi was the rampaging id to Aykroyd’s cool, restrained ego. He worked up a sweat while the older man hung back, letting the music do the work.

The Blues Brothers opened, inevitably, with “Sweet Home Chicago.” It’s an ancient blues standard that has been performed by countless artists countless ways, most notably by Robert Johnson, who sang of this new promised land for Southern black Americans at the height of the Great Migration.

My fellow Chicagoan Barack Obama sang “Sweet Home Chicago” in the White House alongside B.B King.

It’s a song I will always associate with The White Sox. For many years, the Blues Brothers’ version of “Sweet Home Chicago” played when the White Sox won. I consequently will always associate that sing-along anthem with victory and winning and the good parts of being a hardcore Chicago sports fan.

Magic was in the air that night. It was tacky and vulgar and in eminently questionable taste but it was also unexpectedly powerful and profound.

Watching these strange men perform sloppy blues for well-fed Midwesterners in a spooky apogee of Midwestern gothic made me realize that, in spite of everything, I still love Chicago.

Loving Chicago became too goddamned painful at some point. I had taken on too much damage. I couldn’t go on. I needed to go somewhere else in order to find myself as a father, writer and man.

I willfully abandoned all of the things that I adore about my hometown because they were inextricably intertwined with the things that were just too goddamned tough to bear.

That night in Joliet I fell back in love with Chicago, home, bittersweet home Chicago. I don’t love Chicago despite it being weird and fucked up and filled with sadness and despair; I love it because it is such a strange and difficult and sometimes dark place.

That’s okay! Life is strange and difficult and often dark. That’s why we sing the blues. That why we listen to the blues. That’s also why we elevate funnymen like John Belushi to the level of Gods because they have the ability to distract us from the world’s brutality.

No idea who these guys are.

It’s not about avoiding darkness and sadness and hurt; it’s about transforming that darkness and sadness and hurt into something joyful and cathartic, of feeling the good pain deep within your bones.

In an early program for the convention, the climactic screening of The Blues Brothers was going to be preceded by a lengthy Q&A featuring Aykroyd and the Beloosh.

I noticed that disappeared from later programs and schedules. During the set, a possibly oblivious Aykroyd said that The Blues Brothers would be playing a marijuana festival the next evening in Niles, Michigan and that we should check it out.

I would love to have gone, but I was seriously locked into attending the Blues Brothers Convention at Joliet Prison. It’s kind of a big deal but also, weirdly, something you can also just kind of blow off even if you are the Blues Brothers guy.

The gig suggested a distinct lack of investment on the part of “The Blues Brothers”, like they were hedging their bets in case no one showed.

For reasons I do not understand, when thanking the people who made the Blues Brothers Con possible, Aykroyd singled out people who helped raise something in the area of three and two and a half million dollars respectively.

That meant that the soiree must have cost over five million dollars at a minimum. It was hard to know exactly where all that money went. I hope they REALLY over-paid all of the blues acts that performed to help make up for, you know, everything.

It all ended up being moot. I was buying a lawn chair for the second night of the convention at Wal-Mart, as one does, when I got an email informing me that due to rain, the festival was closing at 4 PM.

I was bummed but figured I would hold a mini-Blues Brothers convention in my hotel room at the Hollywood Casino Hotel. After ingesting various substances, I re-watched The Blues Brothers on my laptop.

Instead of watching The Blues Brothers in the best possible context—on a giant screen at Joliet Prison alongside hundreds of other deliriously happy super-fans—I would be watching it on a ten inch screen in my lap.

It didn’t matter. I could watch The Blues Brothers on a Gameboy and it would still rock my world. It hit all my nostalgia sweet spots, particularly my fascination with movies as sociological documents and time capsules.

Among its myriad other gifts, The Blues Brothers provides an endlessly mesmerizing look at what Chicago looked and felt like in the summer and early fall of 1979.

That weird, wonderful, abbreviated weekend, I went home in more ways than one. For that, I will always be grateful.

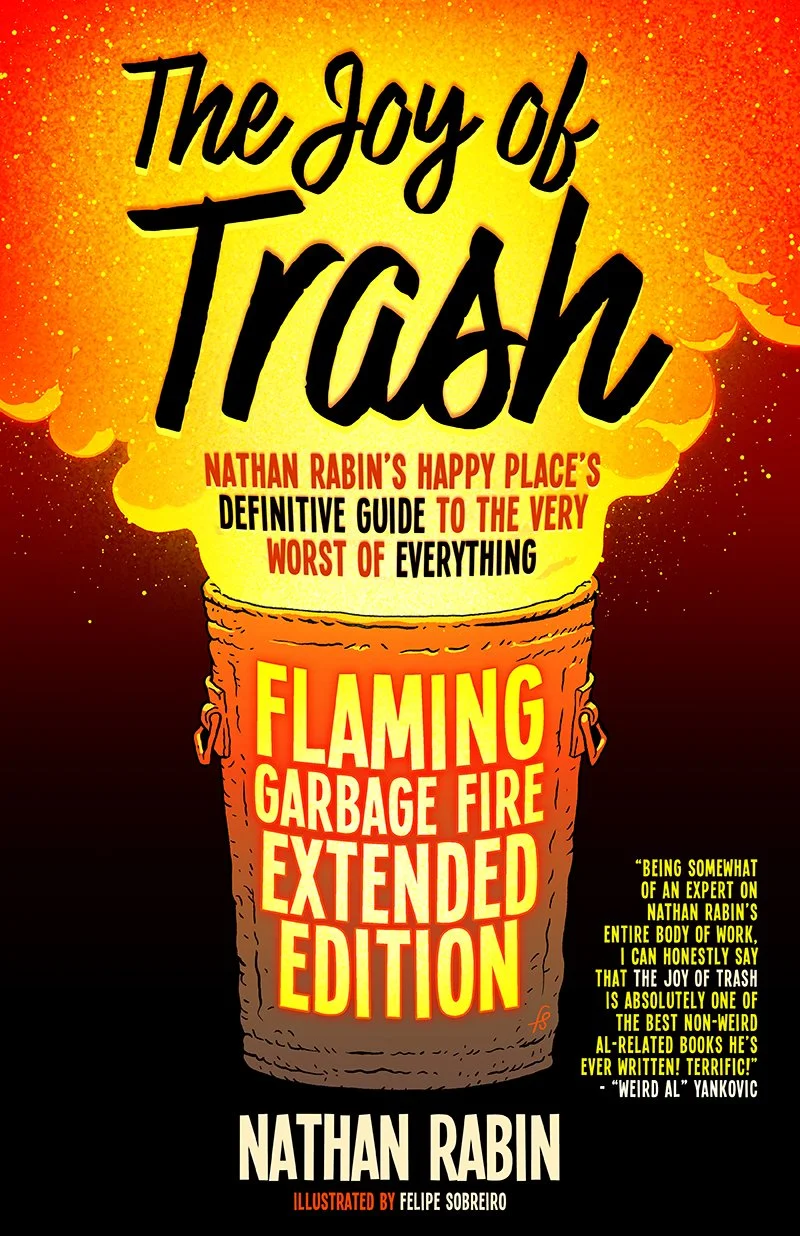

Would you like a book with this exact article in it and 51 more just like it? Then check out my newest literary endeavor, The Joy of Trash: Flaming Garbage Fire Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free, signed "Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring book for free! Just 18.75, shipping and taxes included! Or you can buy it from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Joy-Trash-Nathan-Definitive-Everything/dp/B09NR9NTB4/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= but why would you want to do that?

Check out my new Substack at https://nathanrabin.substack.com/

And we would love it if you would pledge to the site’s Patreon as well. https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace