The Legendary Gordon Parks Sr's Career Began and Ended Strongly With the Seminal Coming of Age Movie The Learning Tree and Powerful Biopic Leadbelly

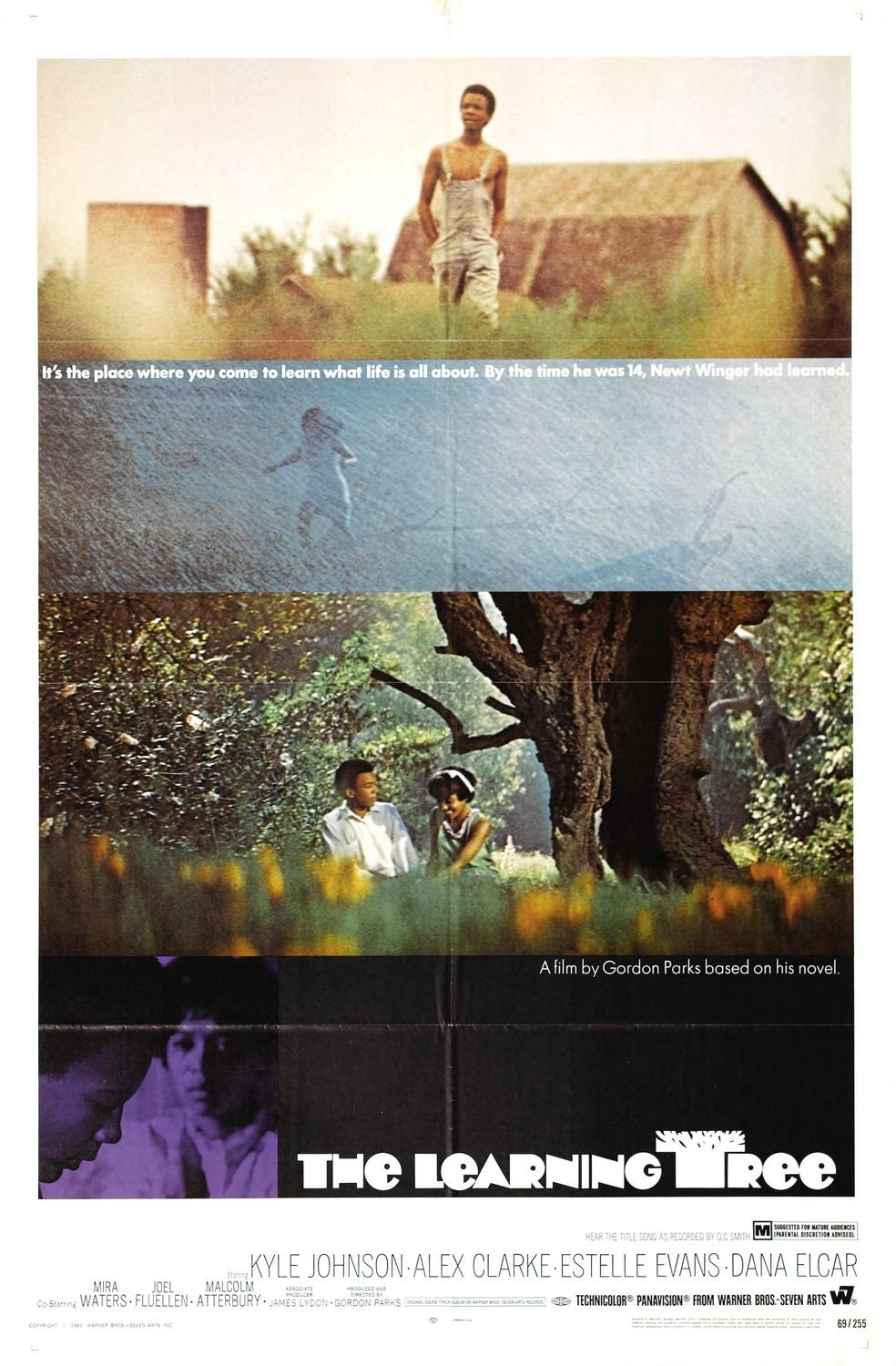

After establishing himself as one of the nation’s top photographers and photo-journalists, regardless of race, Shaft director and all-around national treasure Gordon Parks Sr. made history as the first black man to direct a major motion picture for a studio in the lovely 1969 coming of age drama The Learning Tree.

Ah, but it wasn’t enough for this overachiever to break the color barrier for black filmmakers looking to work in the studio system. Parks didn’t just direct The Learning Tree. He also produced it and wrote the screenplay, as well as the novel it’s based upon. If all that weren’t impressive enough, Parks also composed the film’s score, lest anyone think he was a slacker and not a renaissance man.

When Parks made The Learning Tree he was neophyte when it came to directing feature-length films but he was anything but a newcomer to the arts. He’d published books of photography as well as novels and had made a series of short documentaries. Going into The Learning Tree, Parks possessed all of the skills necessary to become a great filmmaker, including a connection to his subject matter that could not be more personal. Parks knew the world of The Learning Tree intimately because it was the world he grew up in, the world that shaped and molded him and made him the superlative artist he would become.

Rooted indelibly in Parks’ complicated, fraught experiences dealing with race, death and sex in 1920s Kansas, The Learning Tree stars Kyle Johnson (son of Star Trek’s Nichelle Nichols) as Newt Winger, Parks surrogate, a sensitive, smart and willful fifteen year-old trying to navigate the tricky racial politics of his time and his community.

In its early going, The Learning Tree depicts life for Newt and his buddies as idyllic and pastoral, a nostalgic, gorgeous expanse of green trees, swimming holes, youthful shenanigans and skinny dipping.

Life in Kansas in the twenties would be paradise if it weren’t for the people and the toxic institutions. God gave the people of Kansas an Eden of lush, fertile land that they corrupted with racism and brutality, ugliness and violence.

The same swimming hole where Newt and his overalls-clad pals strip off their clothes to cavort in becomes a place of killing and bloodshed more than once thanks to cops who think that a white man’s apple tree has more value than the lives of the black teenagers who purloin fruit, in the kind of shenanigans that would be happily written off as boyish antics if white children did it but is seen as a crime punishable by murder when black teenagers are the guilty party.

Newt is haunted irrevocably by the death of his friend at the hands of a cop and the knowledge that it could easily be him. Newt understands all too well that at any time being black in the wrong place and the wrong context could get him killed, that for black men of his time simply living through your fraught adolescence to become any kind of a man represents an achievement in itself.

His friend’s death by cop gives Newt a sense of life’s urgency and a desire to make something of himself. Not every obstacle that he faces is violent in nature. There’s a wonderful scene where Newt pushes back against a racist white teacher and guidance counselor’s insistence that it would be a waste for Newt or any black child to try to go to college, but then finds a receptive audience in a sympathetic white principal dedicated to bringing the school into the present over the fierce objections of his teachers and community. Race and racism are toxic and ever-present here but they’re also extraordinarily complicated and Parks does justice to racism’s infinite nuances.

Newt spends The Learning Tree navigating a racial line that shifts constantly. Yet there are deadly consequences for transgressing these ever-shifting, fundamentally unknowable boundaries and limitations.

Newt’s friend Marcus (Alex Clarke) deals with the killing much differently. For Marcus, the killing is incontrovertible proof of the world’s unfathomable cruelty. He’s too overcome with rage to be able to play the game of compromise that white society demands he play. He’s not going to scrape or bow or prostrate himself before anyone, even if he’s signing his own death certificate in the process.

The Learning Tree establishes the template for what would eventually be known as the “hood movie,” a coming-of-age genre that flourished in the late 1980s and early 1990s with zeitgeist-capturing hits like Boyz N The Hood, Juice and Menace II Society. But where those movies were urban, The Learning Tree is rural.

Newt is like the protagonists of Boyz N The Hood and Juice, a pragmatic figure of assimilation who wants to get out of a neighborhood that feels more like a prison or a trap than a welcoming home and make it in a white man’s world.

Marcus, meanwhile, is too angry and uncompromising for assimilation. Like Ice Cube’s Doughboy in Boyz N The Hood, Larenz Tate’s O-Dog in Menace II Society and 2Pac’s Bishop in Juice he’s the hate that hate made, a powder keg of barely suppressed rage primed to explode at any moment.

Time has done nothing to dim The Learning Tree’s power or painterly beauty. Parks’ semi-autobiographical drama has aged elegantly, in no small part because it was a gentle period film when it was released. It’s a backwards-looking exploration of its creator’s complicated youth that helped set the stage for the cinematic revolution of blaxploitation and independent black film that would kick into high gear with Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, Parks’ Shaft and Gordon Parks Jr’s Superfly. Needless to say, for Parks and his preciously gifted son, movie-making and icon-creating was a family business.

A mere seven years after The Learning Tree made Parks the Jackie Robinson of studio filmmaking, Parks’ brief but seminal career as a feature film director ended prematurely but triumphantly with 1976s Leadbelly, a wonderful biography of folk-blues legend Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, a man who changed American music forever in between prison stints.

It was a music-saturated biopic epic for the tail end of the blaxploitation era about a larger than life icon. Parks’ admiring but clear-eyed musical drama chronicled for posterity a folk hero as well as a folk musician, a musical genius whose hardscrabble life was shaped irrevocably by the brutal anti-black institutional and personal racism of the time and a never-ending, often losing struggle with his own fierce demons, most notably a violent temper that landed him in jail and on the chain gang at various points in his life when he should have been entertaining sold-out shows and taking his rightful place as one of American music’s true geniuses.

Roger Moseley, who would go on to spend much of the eighties at Tom Selleck’s side on Magnum, P.I., plays the blues pioneer throughout his adult life as a prodigiously, almost scarily talented country boy for whom playing the guitar and singing come as naturally as breathing.

With his haunted good looks, brawling charisma, infectious smile and formidable physique, Leadbelly cut an imposing figure but put a guitar in his hand and he transforms into Superman. He was a strapping superhero of roots music, a sort of real-life John Henry whose talent and charisma opened doors his explosive temper and penchant for violence promptly shut.

Leadbelly didn’t just sing the blues and pick the blues as well as anyone alive. He lived the blues as well. He lived and worked in the places that he wailed about. He understood the agony of the hot box, the misery of being shackled to his follow prisoners on a chain gang under a blazing sun, the sweaty loneliness and desolation of the Southern prison cell.

But Leadbelly was equally at home in funky pleasure palaces like juke joints and the whorehouse where he meets a madam who changed his life and teaches him the blues in more ways than one.

Leadbelly depicts its titular hero as an unabashed hedonist, a man whose weakness for wine, women and song landed him in some pretty dark places. Parks’ film is accordingly a sensual, musical feast for the senses, gorgeously filmed by frequent Clint Eastwood collaborator Bruce Surtees, wonderfully unhurried and percolating happily with wall-to-wall music.

Parks has the good judgment to realize that for all of his remarkable gifts as a storyteller and crafter of unforgettable images, nothing he can do as a filmmaker can compete with the sorrowful wail of Leadbelly’s music for sheer visceral emotional power.

Even at its most joyful, pain is never far beneath the surface in Leadbelly. It comes with being a bluesman, of course. But it also comes with being a black man yearning for dignity and freedom in a time and a place intent on denying the fundamental humanity of anyone that is not white. Leadbelly’s body was imprisoned throughout his simultaneously tragic and triumphant life, but in his music he found freedom.

Pleasure and pain and joy and despair are inextricably intertwined in Leadbelly, just as they are in life. Leadbelly had to experience the blues, and experience it intensely, to be able to exorcise it so powerfully that his music ended up liberating everyone who listened to it, not just a man who sang about life’s vicious brutality as a way of making it bearable. Singing cathartically about seemingly insurmountable hardships gave Leadbelly the tools he needed to survive.

Before Parks broke the color barrier as a studio director, Hollywood was woefully short of representations of black life, particularly from black artists. The success of Shaft proved a double-edged sword for Parks and black filmmakers. Its zeitgeist-capturing success showed that there was an audience for black movies for black audiences, but skittish, safe studios and independent producers gravitated towards cynical, derivative exploitation movies that told the same kinds of stories as Shaft, but without the style and flair. For all its commonalities with blaxploitation (graphic sex and violence, prison, whorehouses, music, a complicated anti-hero, overwhelmingly black cast), Leadbelly told a bigger, deeper and more important story than the gritty narratives found in Shaft or Shaft’s Big Score, which Parks also directed.

The story Parks here was telling was a quintessentially musical one, one rooted in the fertile soil of classic American song. Leadbelly captures the potent essence of the blues, alchemizing profound, infectious joy out of soul-shattering pain. Leadbelly did a whole lot of hard, bad time but it resulted in a unique body of transcendent music celebrated and explored in this New Hollywood-era masterpiece.

It’s unfortunate a talent as profound and singular as Parks didn’t make more movies. Heck, Dennis Dugan has thirty-eight directorial credits to his name and he’s contributed almost nothing to cinema, or society. But we’re fortunate that Parks came along when he did, with credits and a background at the apex of photography too impressive for even racist Hollywood to ignore or deny. He kicked off the studio blaxploitation era with Shaft, sure, but more importantly he told stories that no one else was telling, about tragically under-represented communities in ways so entertaining and successful they helped prove the commercial and creative viability of movies about the black experience to studio heads who only understood profit and attention.

Parks ended his feature film directorial career with a great film about a great American. He began his directorial career on a similar note, only the great American whose unique experience he so masterfully dramatized happened to be his own.

Check out The Joy of Trash: Flaming Garbage Fire Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free, signed "Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring book for free! Just 18.75, shipping and taxes included! Or, for just 25 dollars, you can get a hardcover “Joy of Positivity 2: The New Batch” edition signed (by Felipe and myself) and numbered (to 50) copy with a hand-written recommendation from me within its pages. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind collectible!

I’ve also written multiple versions of my many books about “Weird Al” Yankovic that you can buy here: https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Joy-Trash-Nathan-Definitive-Everything/dp/B09NR9NTB4/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= but why would you want to do that?

Check out my new Substack at https://nathanrabin.substack.com/

And we would love it if you would pledge to the site’s Patreon as well. https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace