Dennis Hopper Changed Everything With His 1969 Debut Easy Rider and Nothing With His Final Film, 1994's Chasers

Like a number of great auteurs I have written about for this column, from Bob Fosse to Garry Marshall, Dennis Hopper would have enjoyed an extraordinary career even if he’d never contemplated directing a movie.

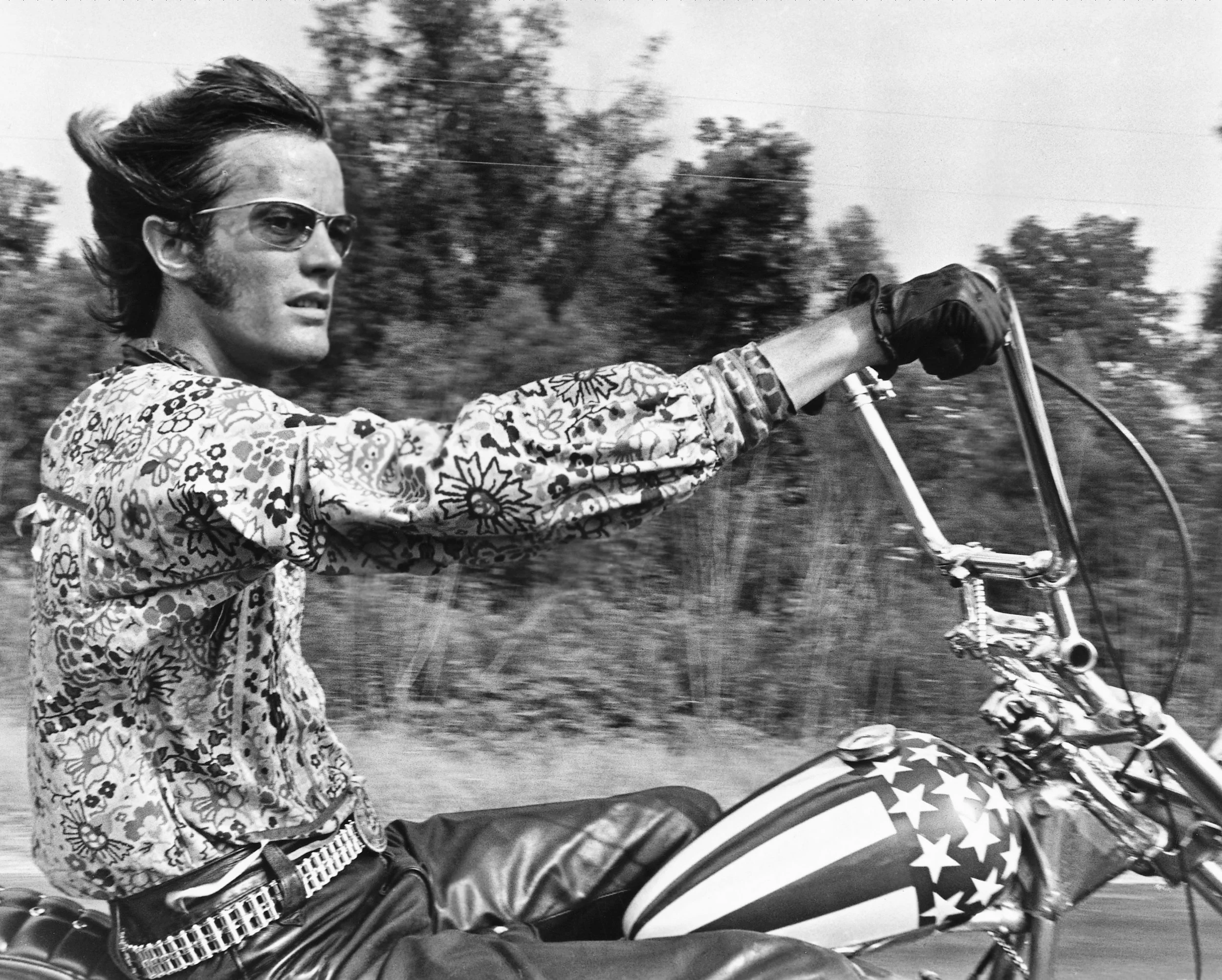

Hopper continually reinvented himself as an actor. He first rose to prominence as a heavyweight method actor pal and contemporary of James Dean, whom he costarred with in Rebel Without a Cause and Giant. Then Hopper became the ultimate hippie maverick outlaw with the release of 1969’s Easy Rider, before becoming the ultimate drug casualty playing the ultimate drug casualty in 1978’s Apocalypse Now.

Hopper got sober and reinvented himself yet again as an Oscar-nominated character actor in Hoosiers and possibly the most charismatically demonic figure in all of cinema in David Lynch’s 1986 masterpiece Blue Velvet. Hopper’s legendary turn as the malevolent personification of evil in Blue Velvet anticipated a late-in-life turn towards villainy in big, mainstream movies like Speed, Super Mario Bros. and Waterworld.

Hopper died at 74 in 2010 a wealthy art collector, Hollywood legend and Republican a world away from the wild-eyed hippie he unforgettably played in Easy Rider. It’s a testament to what an incredible impact Hopper made in beloved pop classics like Apocalypse Now, Blue Velvet and Speed that when the public remembers Hopper and his remarkable contributions to American film, the first image that pops up in their minds is not always going to be of a shaggy and mustachioed young and free Hopper behind the wheel of a motorcycle, luxuriating in the freedom and spiritual ecstasy of the open road alongside platonic soulmate and partner in crime (literal and metaphorical) Peter Fonda as Captain America in Easy Rider.

His first time up to bat as a director, Hopper made a film that can legitimately be said to have changed American cinema, to have ushered in a golden age of daring and artistry in Hollywood, when studio films engaged with the harsh realities of life among outsiders and the underclass in ways they seemingly never will again, because, you know, money.

On paper, however, the low-budget biker movie from a first-time director almost assuredly on The Drugs, must not have looked too different from plenty of other exploitation movies about long-haired young men riding motorcycles, smoking dope, chasing chicks and pursuing some vague notion of freedom that put them into direct conflict with “The Man,” many of them starring Fonda or Hopper.

What set Easy Rider apart was a level of artistry, ambition, soul and beauty that none of its grubby contemporaries from the Corman b-movie factory could approach, let alone match. It also did not hurt that the film’s Oscar-nominated screenplay was co-written by Terry Southern, the legendary novelist and screenwriter whose credits included Dr. Strangelove, The Loved One and The Cincinnati Kid.

Director Hopper, producer Fonda and Southern co-wrote the countercultural touchstone about a pair of dope-smoking outlaw bikers, Captain America (Peter Fonda) and Billy the Kid (Hopper) who decide to use the money they’ve made smuggling cocaine from Mexico to Southern California to fund a trip to New Orleans for Mardi Gras.

En route they encounter a hippie commune engaged in a noble struggle to live off the land in harmony with nature and away from the all-corrupting forces of commerce and end up in jail, where they join forces with George Hanson, an oddball, alcoholic attorney and the ragged black sheep of a prominent family, played by Jack Nicholson in the movie that launched him to superstardom.

How good is Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider? He comes damn close to making you forget Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda in possibly their greatest and most iconic roles. Decades of tacky impersonations and knock-offs and lucrative self-parody have done nothing to remove the freshness and brilliance of Nicholson’s Oscar-nominated, star-making turn here. Oozing devilish sexuality, an impossibly young Nicholson positively burns up the screen as one of the great scene-stealers in the history of American film. It’s a good thing for Fonda and Hopper that Nicholson doesn’t make it to the end of the film or audiences might have forgotten that they were in Easy Rider altogether.

At its best, Easy Rider approaches the effortless transcendence of pure cinema. Hopper and his obscenely gifted collaborators combined music and image in ways that would prove revolutionary. Over a decade before the launch of MTV, Easy Rider fused rock and roll and gorgeously filmed and edited outlaw imagery in a way that resonated with a younger, impatient generation bored with the old way of doing things.

Easy Rider understood that the hippie generation had a connection to music that was too powerful to put into words, that was more powerful than words, more powerful than language. For the free love movement, this overriding, generation-defining passion for music was inextricable from its hedonistic embrace of free love and sensory experimentation with pot and LSD and, in the case of Easy Rider, motorcycles.

Easy Rider was a movie by, for, and about hippies. Hopper was making a movie for a new kind of audience that would look at characters snorting cocaine, or smoking a joint, or dropping acid with palpable excitement and no small amount of vicarious enjoyment instead of sour judgment or disgust. When it came to embodying, and not just chronicling the counterculture, Hopper and his collaborators were the real thing, and audiences could sense that.

In himself, Fonda and, for a spell, Nicholson, Hopper had three utterly magnetic subjects who didn’t have to do anything, really, to be captivating, for the camera to adore them. For all of its rightly revered set-pieces involving the jail, and the diner, and the whorehouse and cemetery acid freak out, many of Easy Rider’s most enjoyable moments come from the endlessly fertile terrain of Fonda and Hopper silently exploring the highways and back roads of our sometimes great land to the accompaniment of a rock and roll song, the wind in their hair, smiles on their faces.

Fonda and Hopper make for one of cinema’s all-time great duos. They’re a complementary pair of opposites, physically and personality-wise. Fonda is tall and lanky, Hopper short and mustachioed. Fonda is all stoic dignity and laconic self-restraint. Hopper, in sharp contrast, is a manic, chattering force of nature.

In its first hour Easy Rider is a deeply American celebration of the open road, small towns and good-hearted people trying to find their own truths and cast off the lies and conformity of mainstream society. Hopper’s vastly influential directorial debut grows darker and darker the closer it gets to New Orleans. Easy Rider ends on such a stone-cold bummer of a note that it’s easy to overlook how much joy it takes in the people and places and faces of our crazy American parade. The lightness, beauty and nomadic bliss of the film’s first two acts make the turn into darkness all the more shattering.

Easy Rider elevated the sweaty, sleazy conventions of the outlaw biker movie to the level of high art. Hopper made his reputation as a filmmaker with a tragedy on two wheels, an elegant meditation on the price of freedom and the cost of the American dream that would explode in ways its makers could never have imagined.

To paraphrase some of Nicholson’s dialogue about space aliens, Easy Rider represented such a devastating blow to the studio system that its aftershocks are still being felt strongly to this day.

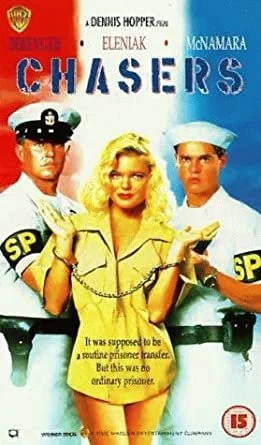

If Easy Rider famously CHANGED EVERYTHING, defining a generation and whatnot and launching New Hollywood along with 1967’s Bonnie & Clyde, then Hopper’s final film as a director, 1994’s Chasers, can safely be said to have changed nothing. Hopper concluded his career as a filmmaker with an exceedingly slight country-fried action-comedy, the kind of trifle you would ideally take in as the lesser half of a double bill at a drive-in in the South.

Chasers’ generic name did not endear the film to the moviegoing public, nor did the existence of a similar movie called The Chase starring Charlie Sheen, the name brand version to Chasers star William McNamara's off-brand knock off, which hit theaters the same year. And it would be difficult to imagine less imaginative or appealing advertising than a poster that relentlessly highlighted the presence of two actors audiences probably didn’t recognize (the aforementioned McNamara, a callow Tom Cruise type) and Playboy and Baywatch alum Erika Eleniak and medium-level star Tom Berenger, seemingly in the film under duress judging by his indignant scowl, Berenger and McNamara in Navy whites, Eleniak in handcuffs and a prisoner’s paper sack-brown garb.

Yes, somehow the moviegoing public was able to resist the siren song of “Berenger-Eleniak-McNamara”, especially when the poster perversely sold this low-wattage combination as the movie’s primary/sole selling point. The film certainly boasted more notable and commercial elements, most notably the director of Easy Rider and Colors in the director’s chair for what would turn out to be the final time.

While Chasers is no lost masterpiece, or even a particularly good film, it highlights what an auteur Hopper really was, how he brought so much to the table with each film, whether it’s a cockeyed patriot’s keen eye for the textures and flavors of our great land, particularly the South, a photographer’s eye for composition or an actor’s feel for getting the most out of every performance, gesture and line of dialogue.

Even when the material was less than stellar, Hopper found ways to put his stamp on movies, to infect them with his wild man personality and sense of craft. Chasers is, for example, a character actor’s delight that finds Hopper dipping deep into his Rolodex and reuniting with fellow heavyweights like Blue Velvet’s Dean Stockwell as an easily distracted car salesman and River’s Edge’s Crispin Glover as a jittery military clerk rightfully aghast at being conned by McNamara’s Sgt. Bilko type. Glover gets more out of a single word like “No!” than McNamara does out of a starring role that leaves a serious charisma void at the film’s core. It’s tempting to imagine what a New Hollywood-era version of this movie might have looked like with Jack Nicholson, Warren Oates and Tuesday Weld in the leads and while the eternally solid Berenger delivers a perfectly workmanlike performance as a hardass who is definitely getting too old for this shit, Chasers suffers from all of its best and most charismatic actors playing supporting roles rather than leads.

Seymour Cassel, Marilu Henner and Gary Busey round out a supporting cast rife with ringers who make the most of their limited time onscreen. The exception, surprisingly, is Hopper, who gives himself the perversely unrewarding role of Doggie, a salesman who picks up Eleniak’s bombshell on the run, barks like a dog and yells something about crotchless panties, then leaves the movie forever. It’s not the most dignified directorial cameo and the movie actually seems to get markedly dumber following Hopper’s weird, regrettable, showboating cameo.

A sort of Touchstone-light slapstick comedy version of The Last Detail, Chasers casts McNamara as Eddie Devane, a Navy grunt, lady’s man and all-around hustler a mere day away from being honorably discharged.

The slick young man’s plan to lay low until he’s out of the military hits a snag when he’s assigned to accompany gravel-voiced, by-the-book lifer “Rock” Reilly (Berenger) in transporting prisoner Toni Johnson (Eleniak), a blonde bombshell eager to avoid spending the next 7 to 10 years of her life in military jail as planned, to prison.

So Toni makes a run for it every chance she gets, using her wiles, her sexuality and a con artist’s instinctive cunning to try to escape from her mismatched captors. Eddie in particular is easily beguiled, and ends up in bed with her in a scene that today raises troubling questions involving power dynamics, consent and free will but at the time seemed exclusively concerned with how hot it would be to see the chick from Baywatch’s naked breasts.

Like Hopper’s aptly named 1990 neo-noir The Hot Spot, Chasers captures the feeling of pounding, laziness-inducing, crazy-making heat on such a visceral level that it feels like the film stock itself is sweating alongside the characters.

Hopper was an unabashed sensualist, in Easy Rider, in Chasers and elsewhere. There’s a tactile quality to Hopper’s compositions. A successful photographer as well as a filmmaker, Hopper specialized in images so vividly and intensely realized that you feel like you can touch, taste and feel them, not just look at them passively.

Hopper had a genius for faces and places, for undiscovered nooks and crannies of our great land, settings bursting with local color and flavor and personality. Chasers has such a nice feel for the backroads, motels and greasy spoons of the South and the ball-busting, macho universe of the Navy that it’s easy to forgive the clunkiness of its dramatic elements and McNamara and Eleniak’s underwhelming performances.

There’s not a lot to Chasers but it’s full of breezy pleasures all the same. Hopper wasn’t out to change film or define a generation this time around. He only wanted to deliver a breezy good time and largely succeeded, in no small part due to the modesty of his ambitions. If Chasers was doomed to be a footnote to Hopper’s epic career as an actor and filmmaker, at least it’s an enjoyable one, one hundred painless minutes at the movies from a consummate entertainer as well as a true American artist.

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!