Francois Truffaut Changed Film Forever with his Debut The 400 Blows and Ended an All Too Brief Life and Career with the Nifty Confidentially Yours

Film critic turned filmmaker and Close Encounters of the Third Kind supporting actor Francois Truffaut (he played the guy with the French accent) was an astonishingly young twenty seven years old when he changed film forever with 1959’s The 400 Blows, only two years older than Orson Welles when he set the all-time record for precocious cinematic genius by making Citizen Kane at twenty-five.

When he shocked and dazzled the world with The 400 Blows, Truffaut wasn’t too far removed from the exquisite agony and feverish melodrama of childhood, adolescence and teenhood himself. He was relatively uncontaminated and uncorrupted by adulthood. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that the exceedingly, impressively young auteur was able to not only remember on a deep, profound emotional level what it’s like to be young and aimless and angry and alone, but to recreate that experience with a verisimilitude and power seldom matched, before or since.

Like J.D Salinger’s strangely simpatico Catcher in the Rye, 400 Blows reveals the world of youth as it actually is, in all of its ugliness and sadness and wonder, and not through the maudlin distortion of foggy-headed adults. Truffaut’s first masterpiece depicts rudderless protagonist Antoine Doinel's (Jean-Pierre Leaud, in the role that would make him a star and that he’d return to four more times, in subsequent “The Adventures of Antoine Doinel" entries Antoine and Colette, Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board and Love on the Run) inveterate rule-breaking and low-level juvenile delinquency as organic components of his personality, not as a pathology. It sees its anti-hero’s reflexive need to rebel at all times as a set of fairly common impulses, not an affliction.

In a performance devoid of the artifice, mugging and studied precociousness that characterizes so much child acting, Leaud plays Doinel as a restless soul and latchkey kid whose life is a never-ending quest for trouble to get into.

400 Blows offers a revelatory portrait of the artist as a young creep, a thief, a liar, a truant, a criminal and a bad influence on other bad boys. In other words, he behaves like a slouchy, sullen, hands-in-his-pockets real 14 year old instead of the patently artificial imitations found in lesser movies about growing up.

Trouble is Antoine’s natural state, his true north. He spends most of the film either misbehaving or being punished for his myriad transgressions but The 400 Blows is no dour message movie about rootless kids drawn to crime and criminality due to a lack of parental guidance. A message of any sort would violate the film’s simultaneously ferocious and casual commitment to naturalism, to verisimilitude, to creating something realer and rawer than anything that had come before it.

The 400 Blows, like Confidentially Yours, the film that would end Truffaut’s beautiful career far too soon twenty-four years later, is filmed in gorgeous black and white. Truffaut uses handheld cameras and overhead shots to create the sense that the camera can go anywhere and do anything, that it is no longer imprisoned by the visual vocabulary of film as it was understood at the time.

It’s as if Truffaut’s camera is freer than any camera before it, that it has been liberated not just from the tripod but from all of the convention and cliche that goes along with it.

We’ve seen the Eiffel tower and the chic neighborhood that surround it countless times before, but never quite like this. It’s as if Truffaut was creating a new language for film as he went along that combined the painstaking craft of art with the startling spontaneity of life.

The 400 Blows is uniquely attuned to the throbbing rhythms of city life, to the hustle and bustle and crowds, to the reflexive rebelliousness of characters in that strange in-between time between childhood and adulthood, dependence and freedom, following the orders of your parents and teachers and authority figures and following the wild dictates of your own wandering spirit.

The 400 Blows liberates the coming of age movie from the strictures of genre, of cliche, of convention, of filmmaker’s insistence on characters learning lessons, growing up and experiencing tidy redemptive arcs. There’s nothing tidy about The 400 Blows, least of all Antoine’s complicated and multi-dimensional relationship with his parents.

Some of The 400 Blows most powerful moments arise out of Antoine’s dawning realization of just how profoundly human and flawed his parents are, particularly a sexy and troubled mother with a complicated past that casts a long, dark shadow over her son’s already complicated existence and wavering sense of self. If Antoine is troubled that’s in no small part because he is the progeny of two profoundly troubled human beings, and he carries that pain and messiness with him as a biological curse.

Antoine begins the film, fittingly enough, by getting into trouble for looking at a girlie picture in class. Over the course of the film, he sinks deeper and deeper and deeper into trouble. Yet in The 400 Blows, trouble and punishment and the never-ending sanction of teachers and principals and jailers is ultimately a small price to pay for the tireless pursuit of freedom at all costs that drives Antoine above any conventional sense of morality.

With 400 Blows, Truffaut created not just a new film, and the first masterpiece in a career full of them, but a whole new way of looking at film, at the world, at young people. The film boasts one of the most rightfully revered and imitated endings in film, a freeze frame on its protagonist on the run (of course) that doubles as an existential question mark.

What does the future hold for Antoine? Can his wild spirit be broken? Further entries in the Antoine Doinel saga would provide answers to those questions without compromising that free-floating air of mystery, of tension, of drama, that characterizes the all-time great final frame to one of the all-time great films of any genre.

Truffaut’s life and career both ended long before they should have, with the beloved, vastly influential New Wave icon dying in 1984 of a brain tumor at the age of 52, to the shock and sadness of multiple generations of cinephiles and movie lovers around the world. He died a martyr, a romantic, a legend, a man who didn’t just make and love cinema but embodied it in human form.

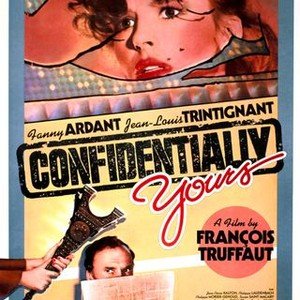

Truffaut at least got to go out on a high note with the 1983 Hitchcock homage Confidentially Yours. The romantic thriller represents a throwback for Truffaut in a couple of different ways. Most audaciously, it’s in black and white, which was already anachronistic back in the late 1950s and 1960s when the New Wave was employing it in movies like 400 Blows and Breathless.

But the film’s deft use of black and white, courtesy of Néstor Almendros, who shot one of the all-time masterpieces of color cinematography in Days of Heaven, also hearkens back to the iconic thrillers of Hitchcock, the master of suspense about whom Truffaut, as a journalist, author and eternal student of film, quite literally wrote the book on, or at least a seminal tome in the revered 1966 interview book Hitchcock/Truffaut.

Truffaut learned much at the master’s feet because Confidentially Yours feels like a dual valentine to Truffaut’s beloved Hitchcock and leading lady Fanny Ardant, who happened to be Truffaut’s offscreen partner at the time as well. Ardant is magnetic and radiant in the juicy role of Barbara Becker, the ass-kicking secretary for Julien Vercel (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a buttoned-up businessman whose life is upended when his deceitful, adulterous wife’s lover is murdered and he becomes a primary suspect.

Julien’s state grows even more perilous when further bodies begin piling up but the flustered businessman is lucky to have a secretary who is secretly in love with him and has the additional advantage of being smarter, sharper and cannier than everyone around here.

It’s a quiet indictment of France’s mistreatment of assertive, aggressive women that a force of nature like Barbara even has to waste her time with dictation and getting coffee for a schmuck like Julien in the first place instead of running the company or moving to England to work for the Scotland Yard.

Julien does not deserve a woman like Barbara, particularly since he spends most of the movie in various sedentary positions, waiting patiently for his much smarter partner to solve the murders he’s accused of, and with them, all of his problems. Then again, nobody really seems worthy of a woman of this stature.

Truffaut famously loved women, particularly actresses. Heck, he made The Man Who Loved Women, which Blake Edwards remade as a Burt Reynolds vehicle (why does the phrase “lost in translation” spring to mind?) the year of Confidentially Yours’ release so it’s unsurprising that Confidentially Yours works smashingly as a vehicle for Ardant, who is funny and fearless, charismatic and sexy.

It would take a heart of stone not to fall hopelessly in love with our leading lady alongside our patently unworthy leading man, who makes for an awfully passive protagonist. It’s not quite on the level of Entrapment, where Sean Connery’s character told Catherine Zeta-Jones’ lithe young thief what rigorous physical endeavors she’d need to perform, then seemingly spent the rest of his time sleeping, but there is a similar imbalance when it comes to which half of the team actually goes out there and makes things happen despite the danger and physical peril involved and which half sits back and waits and coasts on being a white man.

Confidentially Yours explores a prototypically Hitchcockian conceit: a pair of relative innocents become unexpectedly accused of a terrible crime, plunging them into a seedy underworld of killers and thugs and secrets they barely knew existed as they struggle to solve the central crimes and by doing so clear their names.

It’s partially due to Truffaut’s work as an author, specifically with Hitchcock/Truffaut, and partially due to his direction of movies like this that Hitchcockian is an adjective with a pretty clear-cut definition. Confidentially Yours is Hitchcockian in the best sense, a graceful and elegant tribute to one of its creator’s true Gods that moves along at a brisk clip, even if the answer to the mystery ends up being somewhat anti-climactic. That’s okay. With Confidentially Yours, the breezy pleasures lie in the ride and not in the destination.

Thanks in no small part due to the gorgeous cinematography, Confidentially Yours feels like it could have taken place any time between the 1940s and the 1960s. It’s blessed with a purposeful timelessness; with the possible exception of some deeply regrettable perms on bad guys, almost nothing in the film betrays that it was made in the 1980s, and not at either the heyday of New Wave or Hitchcock’s golden age.

Truffaut’s film concludes on note of conventional morality, with our hero and heroine doing the proper thing and getting married, but because this is a French film, she’s also hugely pregnant. After all, you wouldn’t want to just go rushing into things, now would you?

In real life Ardant was living with Truffaut towards the end of his life and would have a child with him the year Confidentially Yours was released. Given the writer-director and sometime actor’s love of women and particularly actresses, it seems fitting that his three children were all daughters.

So while Truffaut died tragically young, the cycle of life continued, and with his awful, unthinkable early death came new life, just as his zeitgeist-capturing debut infused new life into a medium Truffaut loved with his heart and soul and mastered in so many different ways.