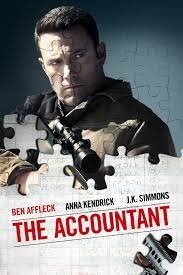

In The Accountant, Ben Affleck Plays a Combination of Good Will Hunting and Jason Bourne With an Autistic Twist

Welcome to the first entry in Autism in Entertainment. It’s a feature where a forty-seven year old man who was recently diagnosed as Autistic explores the fascinating world of entertainment involving characters who are Autistic, or might be Autistic, or seem Autistic but actually aren’t, or seem like they aren’t Autistic but actually are on the spectrum. One of the fascinating things about Autism in entertainment is how ambiguous so much of it is. We’re inundated with characters who are intensely coded as Autistic but never clearly defined as such. There is an element of plausible deniability as well as cowardice in these portrayals. If people find these characters offensive, tone-deaf, unconvincing or otherwise regrettable the creators can say that they aren’t Autistic at all but instead have a condition that is exactly like Autism but different somehow.

The 2016 thriller The Accountant has a lot of problems. Oh sweet blessed does it have a lot of problems. But it can never be accused of not making it one hundred percent clear that its protagonist has the most Autistic case of Autism in the history of the condition. It’s one of those movies that depicts Autistic people as being different in a way that makes them not sub-human but rather super-human.

In The Accountant Autism is a superpower. Its anti-hero can’t make eye contact or engage in small talk but he can kill an entire room full of super-assassins with just a pencil while doing complicated mathematical formulas and curing Cancer.

He’s an impressive human being, is what I am saying. Almost TOO impressive. No wait, I mean he’s DEFINITELY too impressive, to the point where he doesn’t seem to be a human being at all, but rather a warrior angel who is also really good at crunching numbers.

Though he did choose to appear in Gigli, Daredevil and the “Jenny from the Block” video Ben Affleck is not a stupid man. Nor does he lack talent or discernment. Yet he looked at this ridiculous screenplay and decided to devote months of his precious time and energy into making it a reality.

Why? I suspect that it’s because the role of Christian Wolff, super-genius/super-soldier/superhero/super-autistic man-God combines characteristics from Good Will Hunting and Jason Bourne, the signature characters of Affleck’s hated rival Matt Damon.

They say that you should keep your friends close and your enemies closer. Affleck HATES Damon. Who doesn’t? The man is objectively the worst. I doubt he drops by a Dunkin Donuts even once a year. So Affleck makes sure that sick fuck isn’t up to something by working with him extensively over a period of decades.

In the role no one will remember him for, Affleck plays the grown-up version of a sensitive Autistic boy whose mother wanted her son to live in a treatment center for children with Autism. His soldier father, on the other hand, thinks that life will be difficult for his son so he better toughen up by becoming a James Bond-level super-soldier.

So the domineering daddy trains him around the world in the three Rs: Reading, Writing and Ripping Dudes Throats Out. The young man becomes the greatest killer the world has ever known but he’s history’s greatest mathematical and business mind as well. And all because he’s Autistic. Not bad, eh? Movies love savants. They have much less use for people who are Autistic in more complicated and less glamorous and dramatic ways. All I ever got out of Autism, for example, is intense social awkwardness and the ability to hyper-focus on niche subjects that nobody cares about.

Christopher uses his freakishly advanced psyche to help the bad guys cook the book. Then, like an Autistic Robin Hood, he uses his ill-gotten loot to fund charitable endeavors and stock his sleek airstream trailer with priceless artwork and mint Mickey Mantle rookie cards and other ostentatious displays of wealth.

Everything in The Accountant is needlessly complicated and convoluted. For example, J.K Simmons stars as Ray King, a Treasury officer on the brink of retirement who wants to track down Affleck’s mysterious do-gooder before his last day. Ray wants a young treasury agent named Marybeth Medina (Cynthia Addai-Robinson) to assist him. Rather than just ask her he instead lets her, and us, know that she lied to the government about certain elements of her traumatic childhood and will let the authorities know about her deception if she doesn’t play ball. This adds nothing to the film beyond making it even more pointlessly overwhelmed with subplots and characters begging for the cutting room floor.

Jon Bernthal stars as a vicious killer whose relationship with the hero is supposed to be mysterious when I guessed that he was the hyper-competitive brother who figures prominently in flashbacks within his first few seconds onscreen. Bernthal isn’t bad. He never is. But he does not have a character to play. He has no agency or inner life. He just exists to oppose THE ACCOUNTANT and move the plot forward.

Actors who play Autistic characters, or Autistic-coded characters often fall into two camps: they’re either robotic in their depiction of Autistic folk as unemotional and flat or they deliver hammy performances full of tics and mannerisms.

Affleck falls into the robotic camp. He plays the impossible, improbable hero as someone who can do anything other than behave like someone neurotypical. The problem with the character and the performance is that Autism isn’t an element of THE ACCOUNTANT: it’s the entirety of Christopher Wolff. Everything that he does or says or thinks is determined by his Autism.

This extends to his relationship with an assistant played by Anna Kendrick who learns to appreciate her unusual boss when he saves her from being killed by the bad guys. THE ACCOUNTANT’s emotional arc entails going from treating the beautiful woman in a dispassionate, wholly professional fashion to treating her with affection.

I’ve been intrigued by The Accountant because its Wikipedia entry makes it seem so bizarre and so potentially offensive. On paper the surprise hit seems like loads of unintentional laughs, particularly since the filmmakers take the pulpy premise so seriously.

The Accountant perplexingly is oddly devoid of unwanted chuckles but it’s also devoid of intentional humor. It plays a preposterous plot perversely straight in a way that keeps the movie from being dumb fun but also doesn’t result in it working on a non-ironic level either.

The Accountant did quite well. It made over one hundred and fifty million dollars on a modest budget and there was talk of a sequel but I’m not sure there’s any life left in this unique portrayal of Autism as being akin to being a meta-human who also possesses Mossad/NAVY Seal-level fighting skills.

In that respect it’s appropriate that my journey begins here, because The Accountant embodies, in an unusually pure form, the many cliches and conventions that make entertainment about Autism so consistently frustrating and angry-making.

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here