My Journey Through the Cult British Science Fiction Show Red Dwarf Begins with "The End" and "Future Echoes"

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the career and site-sustaining column that gives YOU, the kindly, Christ-like, unbelievably sexy Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch and then write about in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to seventy-five dollars for all subsequent choices.

Welcome, friends, to the beginning of another adventure! A kind patron has once again anted up for me to write about a television show’s complete run rather than an individual movie or album.

I am pleased to announce that we are heading over to jolly old England, a country torn apart by the insouciance of that dreadful Meghan Markle woman and the jerk she married yet atwitter with excitement and anticipation over King Charles’ impending death.

It is a strange country with a strange culture and a strange currency, where everyone talks in a crazy accent and drives on the wrong side of the road. Do you know what they call Big Macs over there? Probably Big Macs.

We’re hopping into the Wayback Machine and traveling to the magical year 1988, when Red Dwarf, a plucky science-fiction sitcom based on a series of sketches from the BBC Radio show Son of Cliché, debuted.

I’m going into this journey blind. An hour and a half ago, I knew nothing about Red Dwarf. Now, having watched the first two episodes for Control Nathan Rabin 4.0, I am a changed man.

The show was inspired by John Carpenter’s low-key masterful 1974 debut, Dark Star. Carpenter’s quietly influential first masterpiece depicted working on a spaceship as just another blue-collar job, and not a particularly good one at that.

Dark Star pioneered the concept of grungy, stoner science-fiction rooted in funky dark humor and countercultural rebellion.

John Carpenter inspired Red Dwarf. Red Dwarf fan Matt Groening, meanwhile, was no doubt inspired by Red Dwarf when he co-created Futurama with David X. Cohen.

Both cult science fiction comedies center on hapless everymen who are croyogenically frozen/kept alive in a state of suspended animation and then dropped into a distant future they struggle to understand.

And both shows have a bittersweet sense of melancholy derived from its lovable heroes being men out of time whose friends and family are all dead.

Red Dwarf’s debut episode, appropriately and subversively titled “The End” is particularly bleak in that regard. In its very first episode Red Dwarf pulled a Transformers: The Movie and introduced a bunch of characters solely for the sake of killing them off.

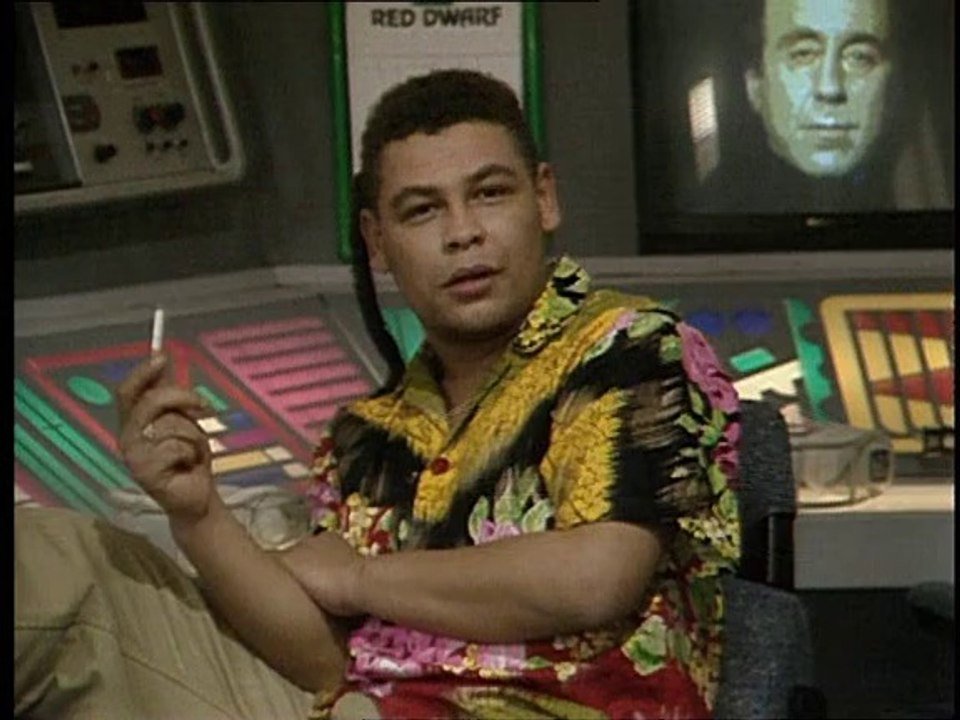

Transformers: The Movie iced its most beloved robot-vehicle-monsters so they could sell kiddies toys based on the new models. Red Dwarf has hero Lister (Craig Charles) spend three million years in stasis after radiation kills everyone human onboard so that he can wake up after the world’s longest nap and find himself in a whole new weird realm beyond his imagination.

Lister is lonely, but he is not alone. He is joined on the ship by Holly (Norman Lovett), a sentient computer with a 6000-IQ, a holographic version of Arnold Rimmer (Chris Barrie), one of his least pleasant and most uptight coworkers, and a sentient talking toaster.

In a line that’s both hilarious and says everything that needs to be said about Rimmer and how he sees the world, he says of the crew cut he’s anticipating getting, “As my father always said, shiny new boots and a shiny short haircut and you can deal with anything. That was before that rather unfortunate suicide business.”

Lister is particularly surprised to discover that the pregnant cat that led to his punishment has served as an important link in an evolutionary chain and that cats have evolved to the point that they are now more or less indistinguishable from humans.

Red Dwarf postulates that if cats were to achieve a human state of evolutionary development, they’d behave like a flashy, narcissistic black soul singer. The anthropomorphic feline here is half The Time frontman Morris Day and half 9 Lives mascot half Morris the Cat.

Cat (Danny John-Jules) is a man-cat with unmistakably feline predilections like licking milk from a plate and chasing after mice.

“The End” opens by suggesting that it will be a much more conventional science fiction workplace comedy. We open in the 23rd century with a funeral for a co-worker that doubles as an introduction to his posthumous existence as a hologram.

“Don’t think of me as dead”, the man quips, “think of me as no longer a threat to your marriages.”

Red Dwarf is full of droll lines like that. Because it is a sitcom from the late 1980s, it has a laugh track. As a child of the 1980s, I grew up with laugh tracks, but even then, they struck me as strange, manipulative, and wrong.

If you’re not laughing along to a show a laugh track can feel simultaneously distracting, manipulative and fake. Laugh tracks are much less distracting when shows are actually funny, and the audience gets to join in on all the guffaws.

Thankfully, Red Dwarf is as funny as it is strange and dark, and it is plenty strange and dark.

After all, this is a show in which a sentient computer reminds our hero, and by extension the audience, that everyone he knows is dead, then reminds him again and again.

“The End” destroys the world that Lister knows so that it can hurtle him madly into a future where everything feels half-mad and just barely in control.

Things spiral in the next episode, “Future Echoes.” One of the things that I enjoy about “The End” and “Future Echoes” is the tone of ramshackle, woozy looseness.

Like the best science fiction, it feels like anything can happen and that the surreal nature of space and space travel drives everybody more than a little bit insane, even under the best of circumstances.

In “Future Echoes,” the ship, having accelerated for three million years (that’s a long time), passes light speed. At that point, it seems to have created some manner of rift in the time/space continuum that throws everything into chaos.

The beleaguered crew seems stuck in a time loop, repeating the same actions and growing steadily loopier as they progress. It’s a mind-melting time warp where, among other oddities and absurdities, Lister meets his future self, sees the children he will eventually father, and prevents his own death.

Craig Charles makes for a terrific straight man. He looks like Hermes and serves as a terrific, likable, and relatable audience surrogate for all of the weirdness like Fry.

I quite enjoyed the first two episodes of Red Dwarf. I don’t know that I would have sought it out of my own accord, what with the several billion other entertainment options out there, but I am excited to have begun this journey and pumped to see where it will lead.

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here