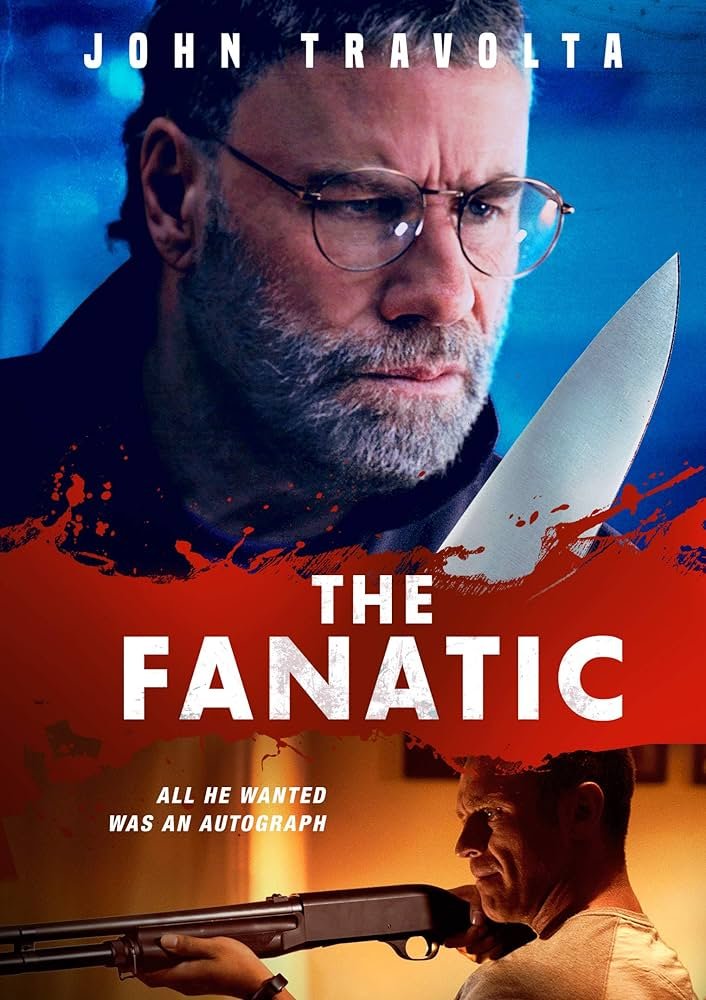

Now That I Know That I'm Autistic, I Find Fred Durst's 2019 flop The Fanatic Even More Offensive Than Before

A lot has happened in the five years since the release of 2019’s The Fanatic. Inspired partially by my morbid fascination with Fred Durst’s poorly received John Travolta vehicle, I embarked on a massive multimedia project to determine which Face/Off star is objectively better, John Travolta or Nicolas Cage.

It only took me and Clint Worthington, my Travolta/Cage podcast cohost, a few episodes to ascertain that Cage is the greater movie star, actor and pop culture icon. It’s not even close. The man is a legend. It doesn’t get better than Nicolas Cage. But I also love John Travolta. If I did not love Travolta I would not have willingly, of my own accord, pursued a project where I watch every film he’s made, even the bad ones.

I now possess a granular knowledge of Travolta’s film career. I know everything about him. I’m unhealthily invested in both his and Cage’s careers.

On Sunday night, I went to Ameris Bank Amphitheater in my neighborhood to see Corey Feldman open for Limp Bizkit. Feldman was there but didn’t perform, but I got to experience the tacky transcendence of watching a bored fifty-something millionaire take his fellow senior citizens on a magical carpet ride back to the wonderful world of 1999, when the band was on top of the world, and nothing mattered more than mindless destruction.

More importantly, in the past five years, I discovered that I am autistic, as well as the father of two autistic children. That made the movie’s subject matter queasily personal for me.

Yesterday, in a My World of Flops piece for The A.V. Club, I wrote about how Ron Howard’s ill-fated adaptation of J.D. Vance’s memoir used to be merely bad when it spent 117 painful minutes fellating its subject for being an American hero when Vance was just a business bro.

Howard’s insane hagiography became evil when Vance used it to rocket into the national political scene as a sycophantic attack dog of a gold-obsessed billionaire he previously compared to Hitler, and not in a flattering way.

It is never established through dialogue that Moose, the painfully awkward perpetual outsider that John Travolta plays with sweaty commitment and an aggressive disdain for subtlety and nuance in The Fanatic, is autistic.

It’s not necessary. In The Fanatic, Travolta embodies every last poisonous, toxic cliche about autistic people being unhinged, violent, unwell, and so mentally ill and lost that they’re beyond help or pity.

The Fanatic’s cold, compassionless portrayal of autism as an embarrassing freak show recalls earlier depictions of trans people as dangerous criminals and freaks leading bizarre, dysfunctional lives on the fringes.

Entertainment clung to that hateful, transphobic conception of trans life as exotic and extreme and dangerous for decades. It’s taken a very long time for those ubiquitous cliches to fall out of favor.

Thankfully, we’ve made tremendous strides in the way autism is portrayed in pop culture in the past half-decade. That makes The Fanatic even more appalling. It’s only a few years old yet clings to an antiquated conception of life on the spectrum.

One of my autistic hyper-fixations involves listening to true crime podcasts. I can’t get enough! I’m subscribed to fifteen to twenty podcasts, at least.

Listening to true crime podcasts involving an overly suggestible young person being manipulated or tricked into committing a crime, I sometimes find myself thinking, “Please don’t be autistic, please don’t be autistic, please don’t be autistic.”

This generally comes a minute or two before the podcast host reveals that their traumatic childhood was exacerbated by neurodivergence of the autistic or ADHD variety.

I don’t want my fellow autistic people to commit crimes and end up in jail or worse. I also don’t want the neurotypical world, and the neurodivergent world, for that matter, to see autistic people as sketchy and easily manipulated and prone to criminality. I don’t want those ugly stereotypes perpetuated.

I want autistic people to be portrayed with dignity and compassion and not as props to aid in a neurotypical protagonist’s spiritual evolution.

The Fanatic consequently offended me on a moral as well as a creative level. On paper, I have much in common with its protagonist Moose. We’re both autistic. We wear the same clothes every day as if we were cartoon characters. We both carry a backpack everywhere we go, deep into middle age. Our diets are both milkshake-heavy. We’re unhealthily obsessed with pop culture, particularly horror movies. We both have difficulty understanding social cues and the world around us.

The crucial difference is that I like to think of myself as a multidimensional human being with dignity who happens to be autistic, whereas Moose is a grotesque, insulting, regressive caricature.

The Fanatic is a movie I hate full of elements that I love. I adore movies about the film industry, or I would not have devoted years of my life to researching and writing The Fractured Mirror, my massive upcoming book on the subject. I similarly would not have spent long, often painful years watching every last stinker a man rightly synonymous with garage made if I was not a huge John Travolta fan. Lastly, two of my favorite movies are Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. The Fanatic rips off those two Martin Scorsese cult classics as shamelessly as Joker and with even less artistry.

The Fanatic is no Big Fan, a nifty, eminently rewatchable cult classic that I am quite enamored of. I suppose you could even say that I am a major supporter of Big Fan.

In a performance that will make no one forget Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver, The King of Comedy, or Patton Oswalt in Big Fan, Travolta plays Moose, a bike-riding misfit whose life revolves around getting autographs, watching horror movies, and hanging out at a memorabilia store where the owner knows and tolerates him and his eccentricities.

Moose has the same backstory as Jim Carrey’s similarly pop-culture-obsessed sociopath in The Cable Guy. In both films, we’re treated to a single flashback of the sad antihero/villain watching television as a boy with the volume up so high that it drowns out the sounds of his single mother drunkenly coming home with her latest one-night stand.

The psychology is less cheap in The Cable Guy because it is a dark comedy rather than a failed psychodrama, but the inference is the same: Daddy wasn’t around, and Mom was too busy shtupping random dudes to be there for her son, so these lost little boys were raised by television and pop culture that taught them all the wrong lessons.

Now that I think about it, Carrey’s character in The Cable Guy is heavily coded as autistic as well, but the film came out before the big recent boom in visibility and acceptance.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s apparent that Carrey’s Chip and Travolta’s Moose don’t understand the world and their place in it because they’re on the spectrum, not because their deadbeat daddy didn’t go to their little league games and mommy slept around.

Moose ekes out a living making the world’s worst impression of an English bobby on Hollywood Boulevard. It’s a bewildering choice for a character, particularly since he’s playing a generic English police officer and not, say, Charlie Chaplin’s little tramp character.

Nothing about Hollywood Boulevard says “English” or “cop,” but Moose remains committed to the character.

The sad sack’s miserable grey existence changes forever when he learns that Hunter Dunbar (Devon Sawa), his favorite actor, will be doing a signing at the memorabilia shop that is Moose’s home away from home.

The signing means nothing to Hunter and everything to Moose. The lumbering oaf becomes dysregulated when he’s waiting impatiently in line for an autograph when the B-list action hero is called away to handle personal business.

Hunter has a messy private life as a divorced single father with an on-again, off-again sexual relationship with his maid. I’m a fan of Chucky, which casts Sawa in multiple roles, all of which he handles with aplomb.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, Sawa’s performance here is distressingly one-note. He’s a perpetually apoplectic alpha male who responds to Moose’s clumsy attempts at forming a connection with barely suppressed rage. He’s impossible to like and difficult to relate to.

Durst and co-screenwriter Dave Bekerman have written a screenplay devoid of empathy and compassion. The protagonist and antagonist are both violent monsters filled with incoherent rage.

The Fanatic is a would-be dark character study that looks down on its characters from an unearned place of superiority and judgment. There’s a cold emptiness where the film’s heart and soul should be.

By this point, I have seen The Fanatic three or four times. It’s not only bad but amoral, but it maintains a trainwreck fascination all the same, if only for the gloriously exquisite moment where Hunter Dunbar talks up the music of Limp Bizkit for close to a minute while playing a snippet of “The Truth” before unhappily encountering Moose in his neighborhood.

At this point, I’ve seen almost every movie Travolta has made. I’ve got maybe ten more to go, and the Get Shorty star isn’t cranking them out the way Cage has been.

The Fanatic epitomizes what makes Travolta such a bad movie icon. He’s giving his all, yet his performance could not be more tone-deaf and offensive.

Durst’s abomination is a fairly recent film, but I’d like to think that we have evolved to the point where a movie that treated autism this way could not get made, and if it did get made, it would be greeted with the righteous rage that greeted Sia’s Music.

Nathan needs teeth that work, and his dental plan doesn't cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here