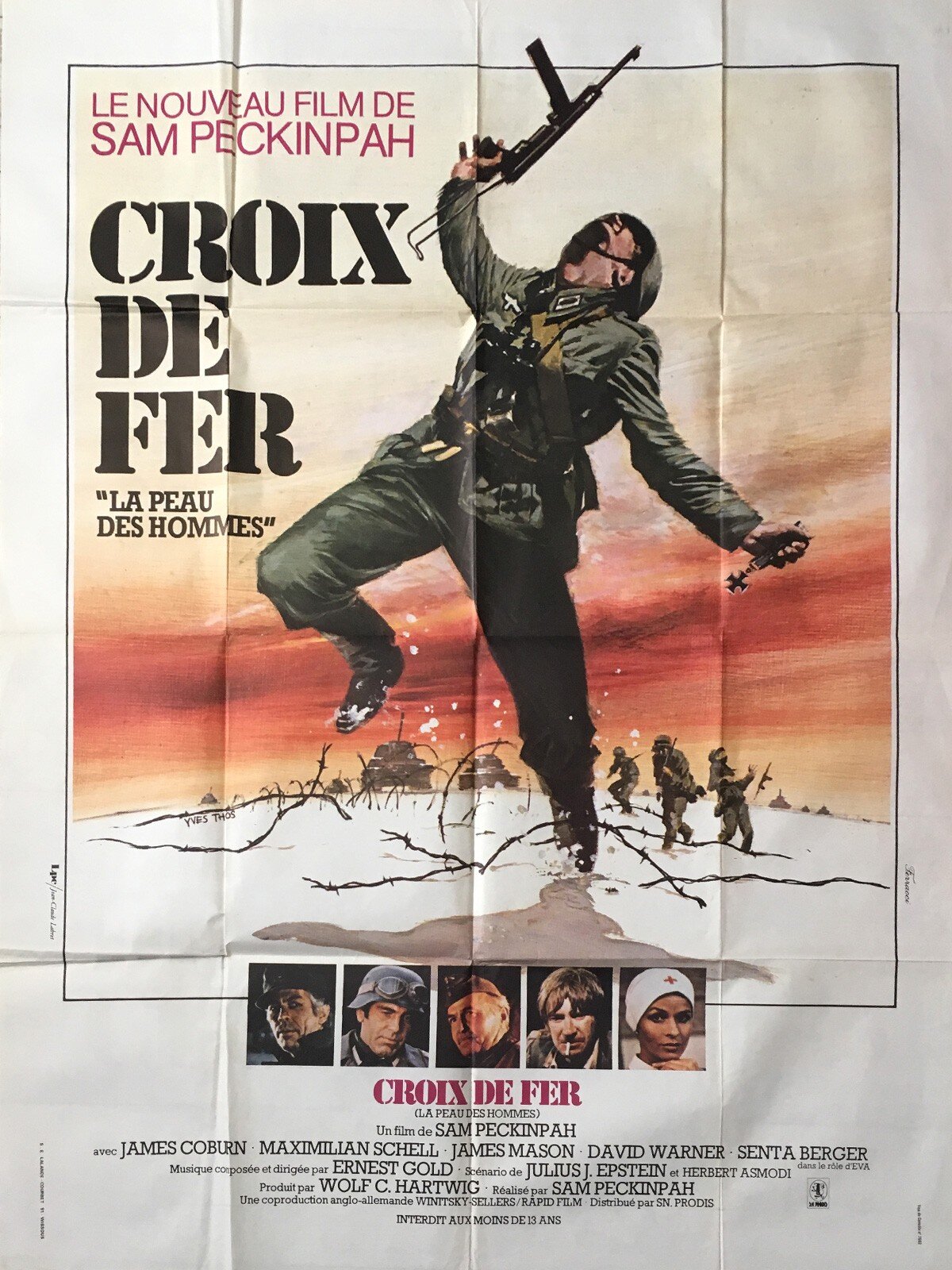

Control Nathan Rabin 4.0 #100 Cross of Iron (1977)

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the career and site-sustaining column that gives YOU, the kindly, Christ-like, unbelievably sexy Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch, and then write about, in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to seventy-five dollars for all subsequent choices.

Or you can be like three kind patrons and use this column to commission a series of pieces about a filmmaker or actor. I’m deep into a project on the films of the late, great, fervently mourned David Bowie and with this entry I have now watched and written about every movie Sam Peckinpah made over the course of his tumultuous, wildly melodramatic psychodrama of a life and career.

I did it! I’ve now seen and written about the western auteur’s complete filmography! And I finished this long, mostly satisfying journey on another landmark for the site and this most essential of columns. To put things in Comedy Bang! Bang! terms, we just hit a hundo!

We’re in the triple digits, baby! Over the course of about two years I have lovingly banged out patron-commissioned entries on everything from Tammy and the T-Rex, an Oscar-worthy magnum opus about a horny, murderous mechanical dinosaur with the brain of a dead jock to Joker, an Oscar-festooned, zeitgeist-capturing blockbuster that’s so fucking terrible I’m getting angry just thinking about it.

Ooh, I hate Joker so much!

I would not necessarily say that I have enjoyed this very thorough exploration of Bloody Sam’s bleak world and blood-splattered oeuvre. With the exception of Convoy, arguably the greatest movie ever made, with the possible exception of Tammy and the T-Rex, Peckinpah’s movies are not supposed to be fun. They’re not supposed to provide popcorn escapism. Instead, they’re designed to provoke. They’re supposed to enrage. They’re supposed to confront audiences with the ugliness and brutality of life on this miserable, cursed planet.

In 1977’s Cross of Iron, Peckinpah’s third to last film but the final movie I will cover for this project, a heroic Nazi officer (an oxymoron to be sure but morality is famously murky and ambiguous in Peckinpah’s films) played by James Coburn opines of his grim predicament, “I believe God is a sadist, but probably doesn't even know it.”

The God of Peckinpah’s movies is Sam Peckinpah himself, although an argument could certainly be made that he’s the devil as well, just as Bloody Sam is at once the hero, villain and anti-hero of his own career.

It’s that amazing that Sam, who I can totally address by his first name at this point in our now chummy relationship, accomplished as much as he did considering that his often glorious career also represented an extensive, intensely focussed and intermittently successful attempt at career suicide.

According to IMDB Trivia, “According to actor Vadim Glowna, Director Sam Peckinpah drank four whole bottles of whiskey or vodka during every day of shooting while sleeping approximately only three or four hours per night.”

I don’t want to be a scold or a puritan but that seems excessive to me. It makes me wonder if Peckinpah may have had a drinking problem and it may have negatively affected his career.

Even by Peckinpah standards, the filming of Cross of Iron was a total shit show. The movie was financed by a German pornographer and ran out of money before filming was complete.

Like its characters, Cross of Iron was doomed. From a commercial standpoint, a movie about the conflict between Nazis and Stalin’s forces on the Russian front was always going to be the hardest of hard sells.

People fucking hate Nazis. They’re the worst! They’re even worse than Joker. How bad are Nazis? They’re literally the Nazis of history. They were so bad that they took their orders from Adolf Hitler, who was exactly as bad as Hitler. In fact, he was Hitler.

Cross of Iron reminds us just what deplorable rogues the Nazis were in an eerie, unsettling opening credits sequence where images of Hitler and the Nazis in action are set to a haunting children’s song sung by a chorus of disembodied, ghostly children’s voices.

Peckinpah’s only WWII movie does not necessarily ask audiences to root for Nazis. That would be insane. But the movie does make clear-cut distinctions between the scheming and nefarious Hauptmann Stransky (Maximilian Schell) and Feldwebel Rolf Steiner, a highly decorated officer with a moral code.

Steiner has virtues we like to think of as fundamentally American: he’s a self-made man of the people who is tough, independent, gutsy, and deeply contemptuous of aristocrats and the notion that he should be deferential towards people higher up the socioeconomic ladder than himself, inside or outside of the military.

More than anything Steiner comes off as a very American Nazi because he’s played by an actor who is not just American but exceedingly American: Peckinpah favorite James Coburn, who was pushing fifty when the film was made, roughly two decades older than the real-life German officer his character is based on.

To muddy the waters even further, two of the other most important Nazis are played by James Mason and dependable Peckinpah repertory player David Warner, both of whom are of course British and don’t even attempt German accents.

It does not help, weirdly enough, that Schell is SO convincing, and entrancing, as a German that he makes all the non-Germans in the film seem even less authentic by comparison.

Cross of Iron opens with defeat all but certain for German forces, though it is unclear what form that defeat will take: friendly fire, a Russian bullet, suicide perhaps or an extended stint in a Russian POW camp.

History may be written by the winners but Peckinpah’s underdog, fatalistic oeuvre is devoted largely to the losers. There’s a wonderful moment in Cross of Iron when a melancholy officer played by James Mason who is all too cognizant of just how doomed he and his men are asks aloud, “What’ll we do when we lose the war?”

That’s a question every German soldier here has to ask himself, because none can afford the dangerous delusion that victory is possible. What do you do when you cannot win, when the only options are death, jail, dishonor or some toxic combination of the three?

With defeat certain, Stransky devotes his time, resources and excess of malevolent guile to trying to cheat his way to an Iron Cross medal he has not earned in a desperate attempt to save face with his family.

Steiner has won enough Iron Crosses himself to know just how little they matter in the grand scheme of things. So when Stransky tries to intimidate Steiner into lying on his behalf in order to win that meaningless bauble to hang on his uniform , Steiner refuses on principle.

Stransky has more success blackmailing Lieutenant Triebig (Roger Fritz) into doing his bidding by tricking him into confessing his homosexuality through lies, intimidation and manipulation.

There’s more than a little of Christophe Waltz’s instantly iconic Jew-Hunter from Inglorious Basterds in Schell’s purringly malevolent Prussian aristocrat. Both men use words and their formidable intellect as deadly weapons. They’re both sonorous masters of manipulation and degradation, men who are exceedingly evil even by Nazi standards.

Waltz, coincidentally, actually made his feature film debut in 1979’s Breakthrough, a follow-up of sorts to Cross of Iron that followed Steiner’s subsequent adventures but re-cast the role with Richard Burton in the lead instead of Coburn.

Cross of Iron is not a great movie but like even Peckinpah’s weakest films, it contains moments of greatness, most notably in its unforgettably repellent villain. It’s hard to root for anyone in a Nazi uniform but it is easy to root for Stransky to get his karmic comeuppance, whether from his own men or the Russians.

Steiner deals with the impending doom of the Nazi cause by trying to survive the war with his limbs, integrity and moral code intact while James Mason’s Oberst Brandt, who is tasked with determining whether Stransky should receive the Cross of Iron, makes it through the bitter end of a brutal, losing, unwinnable battle by envisioning a world beyond war, beyond bloodshed, that offers men of distinction something more than blood and death and mud and exhaustion.

By this point in his career, Peckinpah’s shtick started to feel a little exhausted. Slow motion massacres and gritty revisionism had lost much of their visceral power and freshness through bleary repetition.

Cross of Iron can be very loud and very ugly, with a dirty brown palette that couldn’t help but make me think of shit throughout. The movie’s most powerful moments are also often its quietest, whether in the form of silent slaughter conducted up close and personal or wordless moments of connection between characters.

In the end, Peckinpah was a lot like his characters here: a weary old professional doing the best he can for an inherently doomed cause.

I am exceedingly grateful for both the work and the income that the Peckinpah project provided but I am more than ready to stop seeing and writing about movies in which tough, hard men are machine-gunned in slow motion and women are sexually assaulted as expressions of fate’s unrelenting cruelty.

So goodbye, Sam. Thanks for the memories. Thanks for the movies. But more than anything, thanks for the laughs.

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place and nominate a film (or complete filmography) by pledging at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace

OR you can buy the Happy Place’s new book, The Weird Accordion to Al, a lovingly illustrated guide to the complete discography of “Weird Al” Yankovic, with an introduction from Al himself here or here