Goodbye to Gallagher

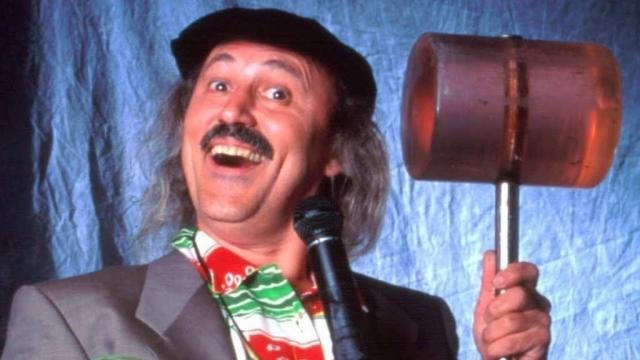

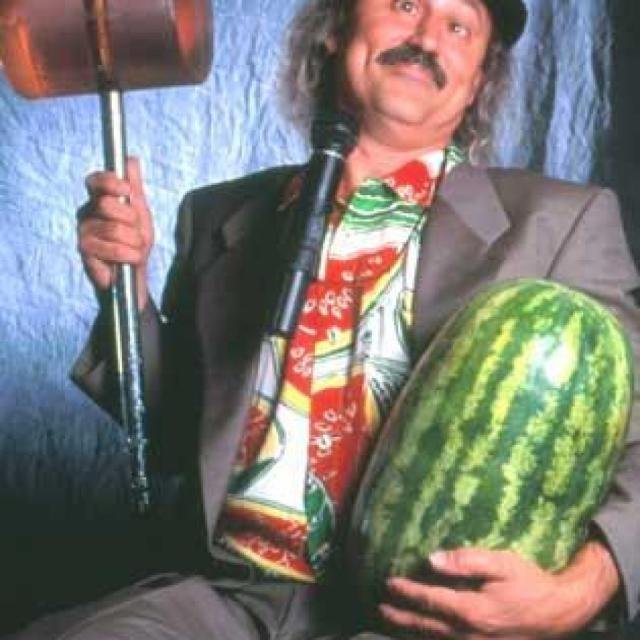

The late Leo Gallagher should have been the most grateful man in the world. For decades he was the king of prop comedy, a form of humor so widely despised that its top practitioners (Gallagher and Carrot Top, pretty much) are walking punchlines and lazy shorthand for hack performers.

With the possible exception of mimes, no one gets less respect than prop comics. Yet Gallagher’s watermelon-smashing brand of tomfoolery nevertheless made him rich and famous, a household name for decades.

Gallagher, however, was not grateful. He was not happy. He did not have a sense of humor about himself, his career, or the world around him. On the contrary, Gallagher’s persona, on stage and off, was defined by anger, resentment and bitterness.

Gallagher was angry at a comedy establishment he felt never give him his props, terrible wordplay intended. He was angry at the world. He was angry at his brother Ron, who he let perform his Sledge-O-Matic routine until he changed his mind and sued him for trademark violation and false advertising. And he was seemingly angry at his audiences as well. He perhaps understandably seemed to have nothing but contempt for people who would pay good money to see him perform.

I once had the surreal experience of watching Gallagher perform at the Gathering of the Juggalos, Insane Clown Posse’s annual festival of arts and culture, in the Comedy Tent during a pounding rain.

I was drunk and high on basically every drug at the time so my stupid brain did not understand why there were so many empty spaces immediately in front of the stage.

So I moved there with my now-wife and immediately discovered why the space in front of the stage was empty when I was reminded of the nature of Gallagher’s act by big, messy, wet chunks of various substances assaulting me and my future bride.

It was ugly and gross but nowhere near as ugly as the nature of Gallagher’s act. He radiated contempt for the crowd, casually insulting the audience at every turn when not directing his rage towards women, minorities and homosexuals.

The moment that stands out most in my mind from that godawful performance was Gallagher sneeringly joking that then-President Obama wasn’t really black: he was the color of Cafe Au Lait.

I don’t know what irritated me more: the unseemly delight Gallagher took in that semi-joke or the idea that the poster boy for entitlement and unexamined white privilege had somehow anointed himself the gate-keeper of blackness.

Gallagher should have been overjoyed that he was somehow able to get thirteen Showtime specials. Instead he seethed with hostility because he thought that with his level of popularity, he deserved more.

A man who won the cosmic lottery over and over again went through life in a state of perpetual agitation because he thought that the universe owed him a late night talk show that would make him as rich and famous as Johnny Carson, Jay Leno and David Letterman.

To an entire generation of comedy fans Gallagher is not a mallet-wielding, beret-sporting enemy of watermelons and cerebral comedy: he’s the thin-skinned buffoon who angrily stormed out of Marc Maron’s WTF podcast after the superstar comedian had the audacity to treat him with insufficient reverence.

The whole idea of WTF is for Marc Maron, a consummate comedy survivor, to provide a safe place for funny people of all stripes to reveal who they are as complicated, three-dimensional people and not just comedians.

Gallagher ended up doing just that but not in a way that reflected well upon him. The late prop comic flew into a rage when the host challenged him, inexplicably defending his bigoted style of comedy as nothing more than “street jokes” that he heard from random people and enjoyed so much that he decided to integrate them into his set.

“Street jokes” might just be a lower form of humor than prop comedy. It’s pretty much on the level of one-liners purloined from dirty joke books. Yet Gallagher nevertheless felt the need to defend the validity and hilarity of street jokes, jokes rooted in stereotypes (two Gallagher offers up before bolting are that Jews don’t like spending money and black comedians only talk about the differences between black people and white people) all the same.

Gallagher’s reliance on street jokes and the way he essentially franchised his act, particularly his Sledge-O-Matic routine, to his brother, betrayed his lack of respect for the art and craft of comedy, as does his anger towards comedians who use the medium to try to say something about themselves and the world around them rather than demolishing fruit.

“Oh, c’mon, Gallagher!” Maron implored his guest in one of the most iconic moments in the history of podcasting after Gallagher left the interview after disparaging multiple fields of non-prop comedy, particularly the kind involving storytelling and truth.

Given Gallagher’s deep-seated anger towards seemingly everyone and everything, it’s not surprising that he had a series of heart attacks over the years.

Gallagher is gone now so at least he’s no longer in pain although I could never quite figure out why he was in pain in the first place, except that he’s one of those straight white men who were given everything by the world yet were apoplectic that they somehow were’t given even more.

Here’s the thing, though. In the time since I wrote this piece I’ve noticed people on my timeline mourning Gallagher. The Gallagher they are mourning seems very different from the public Gallagher but also from Gallagher as he chose to portray himself to the world. They are showing Gallagher a level of empathy, compassion and understanding that he did not show other people, particularly other comics, at least publicly.

It was a reminder that everyone contains multitudes. There are people for whom Gallagher was an important cultural figure, or an icon of nostalgia or childhood joy, or even a friend.

And I want to honor that people’s experiences are different, and there is no one true truth but that certainly was not my experience of Gallagher, and I once had the misfortune to experience him and his cold, grey, toxic anger on a visceral as well as emotional and intellectual level.

Buy The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Cynical Movie Cash-In Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop, signed, for just 12 dollars, shipping and handling included OR twenty seven dollars for three signed copies AND a free pack of colored pencils, shipping and taxes included

Pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 14.00, shipping, handling and taxes included, 25 bucks for two books, domestic only at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!