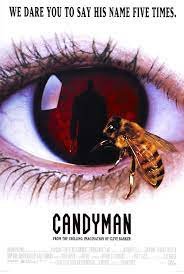

In Honor of the Late, Great Tony Todd, I am Rerunning This Piece on Candyman

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the career and site-sustaining column that gives YOU, the kindly, Christ-like, unbelievably sexy Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch, and then write about, in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to seventy-five dollars for all subsequent choices.

Candyman takes place in Chicago, which I know all too well as a former third-generation resident of the Windy City. It’s a city that’s chilly and cold, violent and sad, where horrible things happen all the time, but people are too beaten down by the inexorable horrors of everyday life to do anything about it.

I went to the University of Illinois at Chicago during my freshman year and was struck by the strange beauty of its architecture and by the otherworldly oddness of its buildings. Candyman makes exquisite use of its Chicago settings to create an ominous world that is gorgeous and horrifying, cerebral and visceral, scary, and ultimately deeply sad.

Candyman is unabashedly a horror film of ideas. It’s a cult classic that has aged like a fine wine and will sadly always be relevant because it is fundamentally concerned with the eternally timely horrors of racism, sexism, grotesque social iniquities, violence, and poverty.

English Writer-director Bernard Rose transformed British fright master Clive Barker’s Liverpool-set tale of supernatural horror into an atmospheric art film/mood piece about everything that makes Chicago, and by extension, the United States, such a fascinating horror show.

In a performance that rightly won her the most prestigious honor in the arts, the Fangoria Chainsaw Award for Best Actress, Virginia Madsen is fantastic as heroine Helen Lyle.

In a role that makes brilliant use of Madsen’s trademark combination of steely strength and aching vulnerability, the future Oscar nominee plays a Semiotics graduate student at the University of Illinois at Chicago studying urban legends.

In the course of her research, the ambitious academic stumbles upon the legend of Daniel Robitaille (Tony Todd, in the role that made him a horror movie god), the cultured, artistically gifted son of a wealthy former slave.

The talented painter became an in-demand portrait artist for the white upper class until his taboo-shattering romance with a white woman led to him having his hand cut off with a saw by an angry mob that then covered his body in honey so that he could be killed by bees.

they have fun!

The way that Candyman handles this information speaks to its artistry, elegance and restraint. We learn all of this from a single monologue from an asshole contemporary of our heroine’s jackass professor husband.

A lesser film would seize upon this grisly scene as an excuse for blood, gore and violence. It would depict this grotesque, tragic spectacle in all of its lurid horror.

That’s not how Candyman treats its unforgettable villain’s backstory. We don’t see ANY of the horrors described. There are no flashbacks. Our minds travel back to that long-ago tragedy but we never leave the expensive restaurant where the scene takes place.

We don’t even see the professor’s face as he tells the story. Instead, Rose makes the bold choice to keep the camera on Madsen the entire time. He knew that merely watching Madsen silently react to someone else’s words for two minutes could be as scary and unnerving as actually seeing the events described.

That choice epitomizes the film’s approach to its material. The Candyman doesn’t even appear until halfway through the movie. Rose isn’t averse to gore, bloodshed, and shocking violence, but he prefers mood, atmosphere, and insinuation.

Helen and her colleague Bernadette "Bernie" Walsh (Kasi Lemmons) visit the notorious housing project Cabrini-Green, the eternal home of Candyman and a harsh realm where all of the failings of capitalism and the American experiment are on full display.

Candyman walks a fine line in being honest about the harsh realities of Cabrini-Green, racism and misogyny without resorting to lurid, racist stereotypes.

That extends to Candyman himself. In a career-making and defining performance, the towering, deep-voiced character actor plays Daniel Robitaille as an imposing, verbose, hypnotic figure. He’s the hate that hate made, a monster created and molded by racism in both its individual and institutional form.

He’s also unmistakably romantic and sexual. He died for love and now seems willing to kill for it as well. There is an unmistakable strain of romantic obsession in his fixation on Helen.

The outsized villain makes dying at the end of his hook seem like the ultimate masochistic display of devotion. For Candyman, death and sex and love and legend are all inextricably intertwined. In his estimation, it is better to die and become instant folklore than to live and have to put up with all the bullshit that Chicago has to offer.

Todd’s performance is rightly revered as one of the greatest and most iconic in horror history. He is the only slasher icon whose defining characteristics, beyond an unfortunate propensity for mass murder, are dignity and a truly impressive vocabulary.

Candyman is scary but also seductive. Todd created a monster for the ages here, but he wouldn’t be anywhere near as effective without such explosive chemistry with Madsen.

That chemistry is inherently sexual. Candyman wants to murder Helen in the most romantic, dramatic possible way and she seems disconcertingly kinda into it. It’s a daring performance that retains an air of verisimilitude no matter how gothic and grotesque things get.

Any realism Candyman possesses comes from Madsen’s ferociously committed but deeply nuanced performance. We believe in Candyman because she believes.

In its second half, Candyman moves away from the grit and social commentary of its beginning and becomes a grim fairy tale about a strong-willed innocent facing down evil.

Candyman lives in a world of myth, metaphor, allegory, and legend. It’s rooted irrevocably in the brutal realities of Chicago in 1992, 1892, and 2022, but it aspires to something bigger and more mythic.

bee my baby!

Candyman is a remarkable meditation race and sex and death blessed with a Phillip Glass score that plays a big role in raising this unusually ambitious fright flick to the level of art. It’s not elevated horror but rather horror that elevates the seedy slasher genre with ideas, style and substance.

Nathan needs teeth that work, and his dental plan doesn’t cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here