Empire Strikes Back Director Irving Kershner's Career Got Off to a Modest but Impressive Start with Stakeout on Dope Street and Ended on a Messy, Riveting Note with Robocop 2

Since it roared back to life with The Force Awakens, the world of Star Wars has been filled with conflict and drama, both onscreen and off. After selling his sometimes beautiful, sometimes embarrassing baby to Disney for billions, George Lucas was famously mortified to discover that Disney’s vision for the franchise’s future did not, alas, include him or his ideas.

2016’s Rogue One, meanwhile, experienced drama of its own when co-screenwriter Tony Gilroy was roped in to direct late in the game re-shoots and Solo was rocked by the firing of the red-hot team of Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, whose improvisational style proved a poor fit for the franchise and producer Kathleen Kennedy, and the hiring of journeyman Ron Howard, whose history with Lucas’ creations goes all the way back to American Graffiti.

Star Wars is famously George Lucas’ brainchild, for better (the original trilogy) and worse (the prequels) but even after the enduring nightmare that was 1978’s Star Wars Holiday Special, Lucas was willing to hand over the keys to other writers and directors, beginning with the very first Star Wars sequel, 1980’s Empire Strikes Back.

The iconic blockbuster was first drafted by legendary screenwriter Leigh Brackett (whose credits include The Big Sleep and The Long Goodbye, and who would not live to see the film made and released, dying in 1978), then rewritten by red-hot newcomer Lawrence Kasdan, who returned to the franchise to co-write Solo and The Force Awakens perhaps because he’s the only person who wrote or directed any part of the original series who isn’t either dead or George Lucas. Being either disqualifies you from working on subsequent Star Wars projects, as far as Disney and Kathleen Kennedy are concerned.

With the eagerly anticipated sequel to Star Wars, Lucas handed over the directorial reins to Irvin Kershner, who began in television and short documentaries before making the leap to movie director with 1958’s wonderfully titled Stakeout on Dope Street, which I am happy to report lives up to the slangy luridness of its title.

The low-budget crime drama has a few other distinctions beyond being the first film of the man who would someday help introduce the world to Yoda, Lando Calrissian and a mess of other beloved pop culture fixtures. Financing for the film was provided partially by an enterprising young man with an eye for both spotting talent and protecting the bottom line named Roger Corman, whose commercial success here led him to suspect there may be a future, and also a fortune, in making movies cheaply and well for young, sensation-hungry audiences.

Though the cinematography is credited to “Mark Jeffrey”, it’s actually the debut film of legendary cinematographer and sometimes director Haskell Wexler, who would win Academy awards for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and Bound for Glory. Wexler’s extraordinarily talent is very much in evidence here, in the film’s gorgeous, shadow-filled black and white compositions, which made the scrappy independent film seem far more expensive than it actually was.

On a less auspicious note, Jonathan Haze, one of the film’s suspiciously middle-aged-looking teenagers, would go on to cult glory the following year as everyone’s second favorite Seymour Krelborn in the Roger Corman-directed cult classic Little Shop of Horrors.

A scrappy, over-achieving cross between deadpan, Dragnet-style docudrama and pitch-black Neo-noir, the movie explores the complexities of the underworld through the tawdry tale of two pounds of pure, uncut heroin that go missing following a drug deal gone bad.

A trio of teenagers, all of whom appear to be deep into their twenties, find the lucrative drug stash and are faced with a Faustian bargain: do they ignore the dictates of their consciences and the laws of our great land and sell the impossibly potent stash they’ve stumbled upon or do they forego a fortune for the sake of doing the right thing?

While the trio wrestles with a moral dilemma, the police and the underworld both set out on city-wide hunts to track down the missing heroin before it disappears completely into the arms and bloodstreams of junkies like a coworker of the teens who agrees to help the boys get rid of their poison, but only after enjoying a taste of it first.

The flashback where a heroin addict shares with one of the boys the brutal tale of how he got addicted to what’s referred to, alternately, as “Happy Dust”, “Snow”, “Mooch” and “Kokomo”, along with more common euphemisms, feels like a powerful short film nestled inside a movie that makes maximum use of its lean 83 minute runtime.

As you might i/magine from a grubby paperback thriller of a movie with a name like Stakeout on Dope Street, Kershner’s gritty debut borders on camp throughout without ever quite devolving into kitsch. The hardboiled narration in particular has a pulpy panache that veers regular into purple prose without compromising the underlying verisimilitude.

In Stakeout on Dope Street, the shamus’ narration has the rat-a-tat rhythms and vivid imagery of beat poetry. The ecstasy of a hero rush is compared to “spending a night on the rainbow”, while the padded room where a deeply scarred heroin addict experiences the disorienting horror of withdrawal becomes “a crazy octopus, twisting down.”

Stakeout on Dope Street’s wild, electric jazz score, heroin theme and haunting black and white cinematography favorably recall The Man with the Golden Arm but without the hokey moralism and laughable descent into melodramatics. With his impressive debut Kershner and his similarly overqualified compatriots gave the world Otto Preminger-level style on a Roger Corman budget.

In true Roger Corman tradition, Kershner worked minor miracles on a shoestring budget with little in the way of resources. The budgets and box-office grosses would get bigger before Empire Strikes Back reinvented the filmmaker’s career.

The filmmaker was so successful continuing the world of Star Wars that he got an opportunity to bring back two of the film world’s greatest icons in the only two theatrically released films he directed between Empire Strikes Back in 1980 and his death at 87 in 2010: the off-brand 1983 James Bond opus Never Say Never Again, which reunited him with Sean Connery, star of his delightful 1965 satire A Fine Madness, and 1990’s Robocop 2.

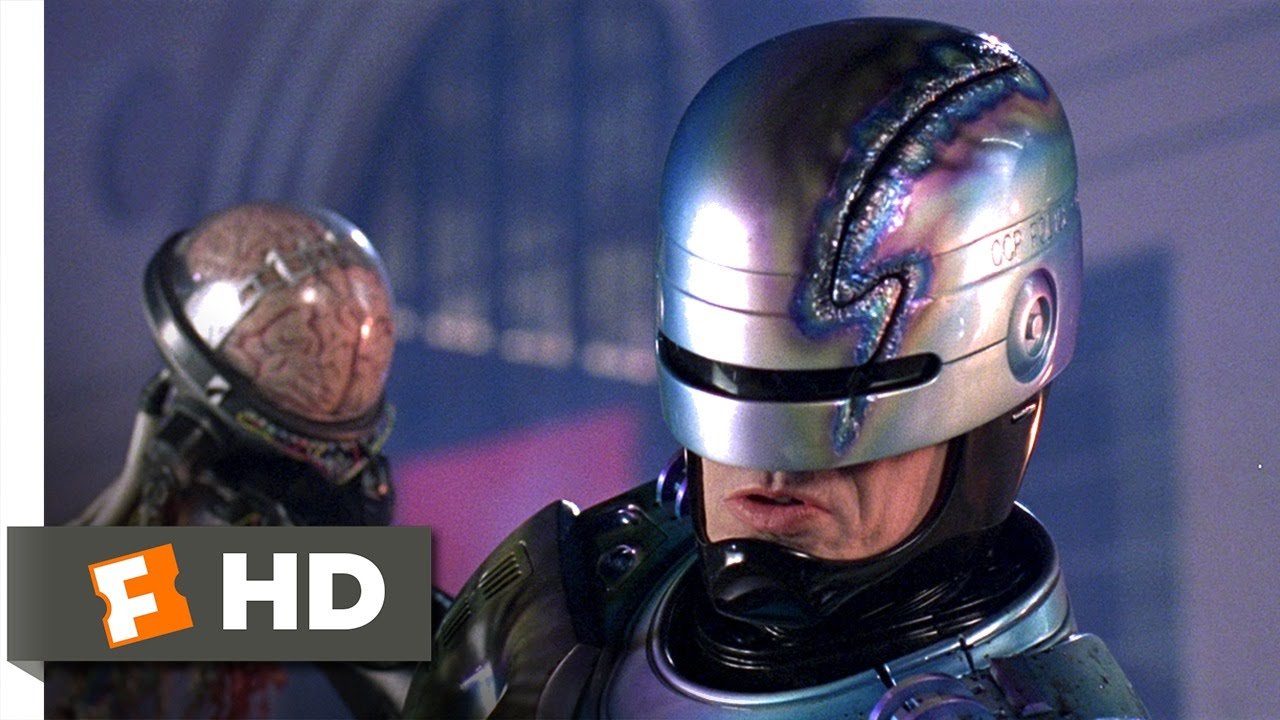

On one level, 1990’s Robocop 2, which Kershner took on late in the game after original director Tim Hunter (The River’s Edge) bailed, marked a return to the subject matter of its director’s very first feature. It’s another tale of a violent city wracked by the insidious poison of drug addiction and a criminal underworld predicated on junkies remaining hooked. Only this time the city is a futuristic version of Detroit as a nightmarish dystopia falling apart at the seams that today’s feels almost uncannily prescient given the city’s real-life problems. Instead of heroin, the scourge of the city is a fictional drug called Nuke and instead of flesh and blood cops delivering rat-a-tat narration Detroit is protected by Peter Weller’s Robocop.

On another level, Robocop 2 is a world removed from Stakeout on Dope Street in terms of tone and genre. It aims not for gritty verisimilitude but rather delirious excess and blood-splattered social satire. The film’s villains are the employees and executives of Omni Consumer Products, the octopus-like corporation that created Robocop and seeks to controls him, and a drug-dealing gang led by Cain (Tom Noonan, typecast as a sneering bad guy with an unmistakable Frankenstein vibe, particularly in the third act). In a larger sense, the primary malevolent force here is capitalism.

Like its predecessor, Robocop 2 finds pitch-black comedy imagining a version of free market capitalism where the sociopathic quest for money and the power that comes with it have overcome all morality, where everything is for sale and everyone has their price.

Like Empire Strikes Back, Robocop 2 is noticeably darker than its predecessor and Robocop is as bleak and despairing as pop blockbusters get, largely because it reflected the sensibility of director Paul Verhoeven, who, needless to say, is not the sunniest of filmmakers.

Though his script was rewritten extensively, Robocop 2 bears the smudgy fingerprints of co-writer Frank Miller, who made his name as a comic book auteur with 1986’s groundbreaking, paradigm-shifting The Dark Night Returns and as a filmmaker with 2005’s Sin City before ruining that name with many of his widely reviled subsequent film and comic book projects and also his personality.

Miller’s gloomy, nihilistic approach to Batman changed the superhero genre for better and worse. Robocop 2 shares with Miller’s superhero work a vision of the world as an ugly, brutal, violent place wracked with disorder and protected by complicated figures wrestling with their own inner darkness as well as the ugliness of the outside world.

Robocop 2 takes place in a Detroit so broke and dysfunctional that a telethon is held to raise money to pay off what to our eyes seems like an absurdly small debt to Omni Consumer Products before the corporation decides to foreclose on the Motor City and take everything private. This invites the question of why even an evil, insane corporation would want to run a city as dysfunctional as Detroit but this is science fiction, so we have to make allowances.

Peter Weller returns for the first, last and only time as Alex Murphy/Robocop, a cross between Jesus, Dirty Harry and the Terminator. Weller doesn’t have much screen time here. Robocop becomes a supporting player in his own movie. When he is onscreen, he’s either suffering unspeakable agonies or he’s killing.

The exception comes is a standout scene where the evil scientists of Omni Consumer Products reprogram Robocop’s personality to make him more public relations-friendly and less terrifying to the average citizen. Suddenly the glowering face of law and order becomes as affable as Mr. Rogers.

The sequence recalls a similarly audacious set-piece in Superman III where Superman gets exposed to a funky Kryptonite-like substance and becomes a super-powered douche bag, a flying jackass. There’s something inherently compelling about seeing such an off-brand version of a beloved American icon. Robocop 2 is overflowing with inspired ideas clumsily executed. The nice Robocop sequence is a good example: it’s a definite highlight that ends in an insultingly idiotic fashion when Robocop is electrocuted and immediately reverts back to his old ways.

In Robo-Nerd mode, our titular hero is less Dirty Harry and more Ward Cleaver, with a little Frasier thrown in for good measure. “Bad language makes for bad feelings” dorkily insists this kinder, gentler, more respectful killing machine. If that it’s true, then this vulgar, profane and unrelentingly nasty dark comedy is the bummer of the century.

For extra shock value, a good percentage of the film’s profanity and violence is handled by Hob (Gabriel Damon), a ruthless and cunning drug dealer and lieutenant of Cain who happens to be an adorable little boy, the kind you’d expect to star in commercials for cereal or toys, not threatening people with a machine gun. Hob may look like a clean-cut, apple-cheeked, all-American lad, but he murders, sells drugs and intimidates public officials into doing his bidding at a college level.

Speaking of insulting plot points, OCP is understandably eager to build more Robocops that they can control, and that won’t be weighed down with problematics “souls” or “integrity” so they create a few who instantly either fall apart or kill themselves. So OCP’s head mad scientist/psychologist Juliette Faxx (Belinda Bauer) decides that if dead police officers other than Murphy make for bad robo-cops, then maybe they’d have more luck working with insane criminals rather than people who’ve devoted their lives to fighting crime.

In a move about as wise and forward thinking as making killer sharks super-intelligent in Deep Blue Sea, OCP decides to put the brain and psychotic psyche of Cain inside Robocop 2, which was designed as the crime-fighting future of android technology but functions more like the drug-addicted, very short lived future of crime.

Yes, that’s right: Cain’s addiction to Nuke remains even after he shuffles off his mortal coil for a metallic exoskeleton that makes him look like a cross between Robocop, Chappie (from the movie of the same name) and a junk drawer that gained sentience and decided to go on a killing spree. The idea is that Cain/Robocop 2’s addiction to Nuke will allow the corporation to control him more easily but that’s astonishingly bad reasoning even for a mad scientist in a science fiction movie.

There’s an appealingly old-fashioned, Ray Harryhausen quality to the climactic battle between Robocop and Robocop 2 that doesn’t do anything to mask the many ways in which Robocop 2 shamelessly replicates the beats, themes and conflicts of its predecessor, but with more violence and profanity and less wit and emotional resonance.

The people who hired Kershner to direct the deeply flawed but intermittently fascinating follow up to one of the biggest surprise smashes of the 1980s were undoubtedly hoping that he’d help create the Empire Strikes Back of opportunistic sequels about robotic law enforcement officers in a dystopian future. Instead they got a sequel to Robocop that’s like the Robocop 2 robot: junky and decidedly inferior to its predecessor but audacious and oddly memorable all the same.

I’m on Subtack now! Check out https://nathanrabin.substack.com/ for my brand spanking new newsletter, Nathan Rabin’s Bad Ideas!

Buy the 516 page Sincere Movie Cash-In Edition of The Weird Accordion to Al AND get a free coloring book for just 20 dollars, shipping and taxes included, at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Cynical Movie Cash-in Edition free!

Pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 12.00, shipping, handling and taxes included, 23 bucks for two books, domestic only at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace